On Monday morning, Karen Smith went to work at the elementary school where she taught in San Bernardino, California. By noon, she was dead.

Smith was fatally shot by her husband, Cedric Anderson, whom she had recently left and was reportedly considering divorcing, according to police. Anderson also shot two of the children in Smith's classroom, killing an 8-year-old boy and wounding a 9-year-old.

The shooting rocked a community already traumatized in December 2015 by one of the nation's worst mass shootings. It also brought to the surface a pervasive, ugly problem of intimate partner homicide that has remained consistent nationwide for years.

According to the Violence Policy Center, which uses Bureau of Justice statistics in annual reports about female homicide victims, nearly three women are murdered every day in the U.S. by current or former romantic partners.

Advocates told NBC News that many abusive partners turn deadly when a victim tries to leave a relationship.

"Lethality increases the moment a woman says she’s leaving," said Tiffany Turner-Allen, program director at UJIMA, the National Center on Violence in the Black Community.

While domestic violence occurs across boundaries of race, class, and gender, black women like Karen Smith are disproportionately affected, according to statistics. African-American women only make up about 13 percent of U.S. women, but comprise about half of female homicide victims — the majority of whom were killed by current or former boyfriends or husbands.

Related: Three Dead, 1 Wounded in ‘Murder-Suicide’ in Classroom

According to Justice Bureau statistics, African-American women are victimized by domestic violence at rates about 35 percent higher than white women.

"Black women are really impacted around violence as a whole, where we’re talking about domestic violence, trafficking, or sexual violence," said Turner-Allen. "The numbers skew very high."

There's no evidence that Smith filed any domestic violence claims against her estranged husband, but her mother, Irma Sykes, told the Los Angeles Times that "the trouble began" when she decided to leave.

“She thought she had a wonderful husband, but she found out he was not wonderful at all,” Sykes told the Los Angeles Times. “He had other motives. She left him and that’s where the trouble began.”

According to San Bernardino police, Anderson had a history of domestic violence.

“Those closest to her said that she had mentioned that his behavior was odd and that she was concerned about his behavior and that he had made some threats towards her," San Bernardino Police Chief Jarrod Berguan said in a press conference Tuesday. "He did not make a specific threat to shoot her. We're also told that from the family that she didn't necessarily take those threats serious. She thought that he was reaching out for attention. "

Anderson did, however, own a gun.

Under current federal law, a person is prohibited from owning a gun if they have been convicted of felony or misdemeanor domestic violence (against a spouse, live-in partner, or co-parent of a child) or if they have a permanent restraining order against them. But they are not barred from gun ownership if they have had a temporary restraining order, a stalking conviction, or a domestic violence conviction against someone they were dating but did not live with or have a child with.

The complexities of the law leave a lot of dangerous gaps, advocates said.

"When a perpetrator has been arrested for domestic violence, we believe their firearms should be taken away," said Monica McLaughlin, deputy director of Public Policy at the National Network to End Domestic Violence.

Related: Florida Woman, Son Fatally Shot In Domestic Dispute

Such a policy would have prevented Anderson from owning the firearm that he used to kill Smith and one of the children in her classroom.

"What we know is that guns and domestic violence are a deadly combination," McLaughlin said. "When perpetrators have access to guns, survivors are in much more danger."

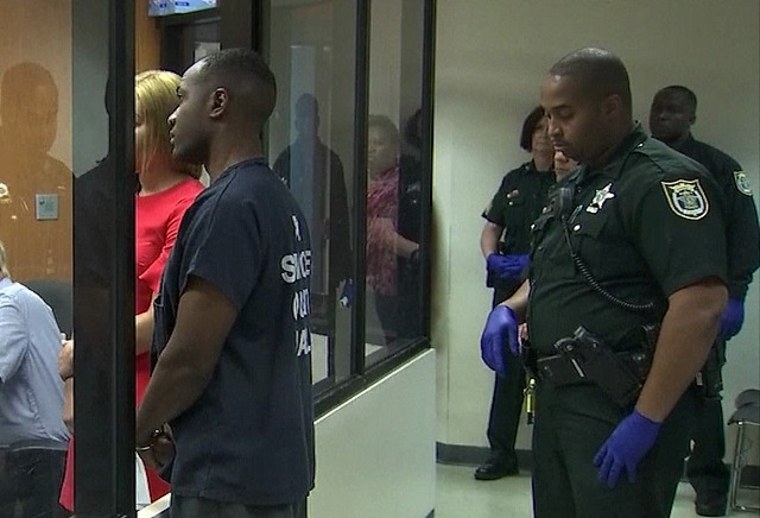

Recent lethal cases of intimate partner violence have raised questions about what law enforcement, the legal system, and advocates can do better to help victims. The deadly shooting of Latina Verneta Herring and her 8-year-old son in Sanford, Florida, last month took place just hours after police arrested, then released, the alleged shooter. Body cam footage revealed that officers released the shooter because they did not believe Herring's claims of abuse.

"She's making false accusations," one of the officers said in the video. "It's the second time she's done it."

Former Baltimore prosecutor Debbie Hines told NBC News that she thinks police departments should employ dedicated domestic violence units.

"They have units for homicide, robbery, and drugs," said Hines, "And the fact that there’s generally not units for DV speaks to the little regard that officers frequently have for the cases."

When asked what needs to change in order to lower rates of domestic violence homicides, Hines sighed and replied, "It’s such a complicated issue."

Particularly for black women, who face higher proportional rates of homicide at the hands of a partner, it starts with the decision to call for help.

"In the black community, for good reason, many people do not trust the police," said Hines. She added that seeking mental health counseling is heavily stigmatized in the African-American community, and a tendency to blame victims — which arose in the social media response to Ray Rice's alleged abuse of his wife — adds to a perfect storm making black women less likely to seek help.

Hines said that even when domestic violence survivors make it all the way to court, and even to a dedicated "DV court," they typically aren't offered supportive services.

Related: ACLU Sues City Over Nuisance Policy, Alleges It Punishes Domestic Violence Victims

"In those courtrooms, they will generally refer the abuser to seek anger counseling or drug counseling or whatever the judge deems, but there’s rarely any support offered to the victim," said Hines. "The courts are focusing on the person being charged."

In some cities and towns, laws even punish victims for trying to get help — with "nuisance" citations and evictions used against domestic violence victims who place more than a certain number of calls to police.

So what can be done to help domestic violence survivors as they reach out for help or attempt to leave dangerous partners?

McLaughlin said 1.3 million survivors go into shelters each year nationwide in order to flee abusive partners, and there are ways to leave safely. Her first suggestion: pairing a victim with a trained domestic violence advocate.

"Together, they can respond to the historical violence and determine what their risks are," McLaughlin said. "We also need law enforcement response that believes survivors, that responds to the calls for help."

She also cited cases where victims themselves were punished for the actions of their abusers, like in the 2013 case of a Catholic school teacher fired from her job when her abusive ex-husband showed up in violation of a restraining order.

McLaughlin said victim-blaming could easily be replaced by simply offering to help.

"Instead of asking, 'Why don’t you just leave,' Ask how you can help," said McLaughlin. "Say: 'I feel scared for you and can see these threats are real.' It’s about closing some of the gaps in our responses."