This story is based on an investigation by the Marshall Project and the Washington Post.

When Kameelah Davis-Spears’s son came home after nine months in juvenile detention for getting into a fistfight with a neighbor at school, she thought the worst was over.

Then, about a year later, she received a summons to meet with Steve Kaplan, a lawyer contracted by Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services. Kaplan told Davis-Spears she owed $12,000 as child support for her son’s time in detention.

"He said he was cutting me ‘a hell of a deal.’ There was no back and forth. He just said, ‘This is what you owe,’" Spears explained in written testimony. "I didn’t have a lawyer there to help me. It felt so one-sided."

Davis-Spears isn’t alone. In fact, charging parents for their kids’ incarceration is common in 19 states identified by a new Marshall Project investigation published in partnership with the Washington Post. In 28 more states, the Marshall Project found that the practice is allowed at the county level.

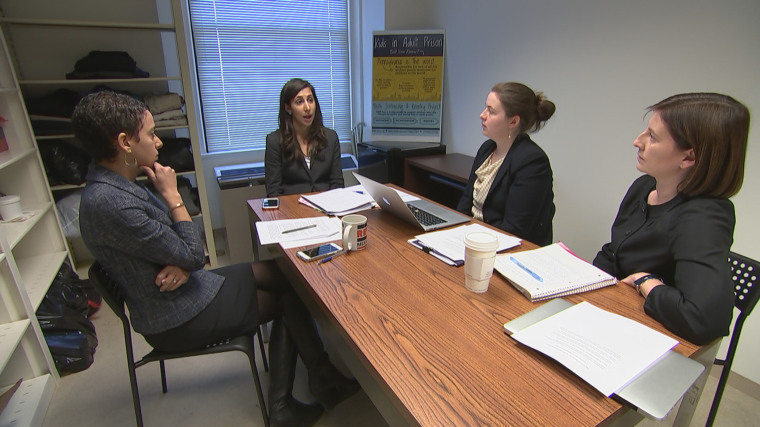

Third-year law student Wesley Stevenson at Temple University in Philadelphia was puzzled by her latest law clinic assignment. The project was to represent low-income working parents being billed for their kids’ incarceration.

"When I first heard about this, you know, I thought that I misunderstood," Stevenson explained, "As an idealistic law student I thought that this couldn't be something that the law was being used to do."

Along with the Philadelphia-based Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project (YS&RP), Stevenson and other Temple University law students in the Justice Lab, a clinic at Temple Law School's Sheller Center, tracked hundreds of Philadelphia parents whose wages and tax refunds were being garnished to pay for their children’s incarceration.

In August, the Juvenile Law Center, a national advocacy group based in Philadelphia, published a report on juvenile court costs and fees across the country and found that inability to pay these fees contributed to youth recidivism, forced children to stay in placement longer, and hindered families’ ability to have a child’s record expunged. In 26 states, children were sent to juvenile detention simply for their failure to pay up.

"Our juvenile justice system is about rehabilitation at its core. And this is doubly punishing children and families after they have come home, which makes it harder for them to continue to stay out of that system and to move on with their lives," said Lauren Fine, co-director of YS&RP.

Proponents of the system argue that taxpayers shouldn’t have to foot the bill for someone else’s child.

But what YS&RP and the Temple University law students have found in Philadelphia is that the collection program actually fails to bring in substantial revenue. The city’s child support revenue from families paying off juvenile detention barely covers the cost of collecting it.

"Some of the support orders that were negotiated were for as little as $2 a day. Some were for $5. The median payment, if you remove tax garnishment, is only $30 a month," Stevenson explained.

Questions about whether the practice is cost-effective have been raised in other counties as well. Both the Marshall Project and the Juvenile Law Center point to Alameda County in California. In the 2014-15 fiscal year, the county brought in more than $400,000 in juvenile court costs and fees — including costs of detention but also expenses for ankle monitors and other fees — but spent over $200,000 to administer and collect those bills. The county later ended the practice in response to those very findings.

NBC News spoke to several parents who had wages and tax returns docked to pay for their child’s incarceration, an experience many say was detrimental to their child.

Tamisha Walker of Contra Costa County, California had to pay for her son’s month in juvenile detention, but she says the then-high school junior was receiving a middle-school education while he was there.

Walker says she paid around $50 for the ankle monitor her son would have to wear for the next three months, but she thought that was the end of it. Walker didn’t know she owed a child-support payment until she got a call from a local collections agency almost a year after her son was released.

The woman on the phone told Walker she owed $300. Walker recalled, "I said I can’t pay that! So the woman said, ‘Well, how much can you pay?’" Ultimately Walker told the debt collector she could pay $100, so she borrowed the money from her mom and paid it over the phone later that day. "It felt like a shakedown."

Advocates for the child-support collection program argue that the system doesn’t present an undue burden to poor families, because parents are billed based on their ability to pay.

Lauren Fine doesn’t think it’s that simple. "Inherent in the idea of assessing someone's ability to do anything — but certainly to pay on a monthly basis — there's at least a presumption that there's a full amount of information going into that decision-making, which in our experience hasn't been the case in the way that this has been done in Philadelphia."

Jonelle Mills, from the Philadelphia area, learned that she owed roughly $3,000 after her daughter spent 10 months in juvenile detention.

When Mills first heard the number, she didn’t know what kind of choice, if any, she had. Initially she understood that she would have small payments garnished from her paycheck over time. Eventually she was informed that the remainder of her debt would be taken from her next tax refund. In February, Mills received confirmation in the mail. More than $2,100 was gleaned from her 2016 tax refund.

"When people are getting the one influx of finances that they get all year, that's when the city is reaping the most benefit from this financially. That indicates, you know, something counter to their ability to pay on a regular basis," said Fine.

Kameelah Davis-Spears has around $54 taken from her paychecks monthly. "I can pay all my bills and I can pay my rent, but that's literally it. Like, the buck stops there."

"The practice operates to target families that are working and that are not on public assistance," Stevenson explained, "I think it's causing them to make choices [that] we wouldn't want any parent to make and that they otherwise wouldn't make, between basic necessities and paying the city."

On Friday, Philadelphia City Councilman Kenyatta Johnson chaired a hearing to review the practice of collecting child support from the parents and guardians of incarcerated kids. "We want to make sure that no young person or their family members are hindered based upon the City of Philadelphia balancing our books on the back of our families who are most in need," said the councilman.

Just hours before the City Council hearing, one day after the Marshall Project published the results of its investigation, and after more than a year of advocacy by the law students, YS&RP and others, the Philadelphia Department of Human Services announced that it would stop billing parents for child support.

In an email sent Friday, DHS Communications Director Heather Keafer wrote, "We are ending Steve Kaplan’s contract on March 31 in order to enable us to proceed in a direction that aligns with Philadelphia DHS[‘s] vision an[d] priorities toward safe and timely reunification of families."

When NBC News reached out for comment, Kaplan confirmed that he is retiring March 31, and said people shouldn’t think of what he does as collecting "fees." "It’s not a fine, not a penalty. No one has a problem with dad paying child support. When a child lives with mom, dad pays. I believe in child support," Kaplan said.

Kaplan said he couldn't comment on the Davis-Spears case or any other specific case, but noted that all parties are advised they have a right to take their cases to a second level, a hearing in front of a master attorney on the record.

When Wesley Stevenson and Lauren Fine heard the news, they were thrilled, but quick to note that their work doesn’t stop here.

"Hopefully we can ensure that the city follows through and that there are accountability mechanisms in place so that no other family has to experience that harm in the future," Stevenson said.

When NBC News spoke to Philadelphia DHS Commissioner Cynthia Figueroa shortly after the announcement, Figueroa noted that the move will put a halt to new collections, but the details of what it will mean for parents like Kameelah Davis-Spears who are currently paying off their debts are still being worked out.

Figueroa is aware the department may receive blowback from taxpayers, but she thinks the issue is simpler than that.

"It was a very small amount of money that was actually being collected, given the amount that it takes to operate the programs that we do," she explained. "We’ve seen more change through prevention and diversionary programs than we have by saddling families with fines."

Another argument of advocates of collecting child support from parents of incarcerated kids is that the payments incentivize parents to be more engaged in keeping their kids out of the system.

"Personally I think that's just a cruel thing to say, because even in situations where the children might be misbehaving, you know, most parents are paying attention," said Davis-Spears. "And when things happen and they kind of get away from them and they kind of lose control. What they need is help, not to have their families torn apart."

Lauren Fine echoed that sentiment. "Parents who have their children forcibly removed out of their homes feel a lot of things already. And accountability is not something that being forced to pay money that they don't really have — that takes away resources from their other children and their ability to pay for necessities — that to me is not about accountability."

The Marshall Project is a nonprofit news organization that covers the U.S. criminal-justice system.