For several members of a Houston robotics team the beginning of another school year brought with it a new morning ritual: wake up, put on a suit and tie, go to the neighborhood doughnut shop.

The time slot before the 8:30 a.m. bell is considered prime selling hours for the young men who parked themselves outside the school for several weeks with a box of fresh donuts to raise money for their school robotics team.

The students were $40 short of being able to purchase drawer slides to use on robots that would compete at their first competition of the season.

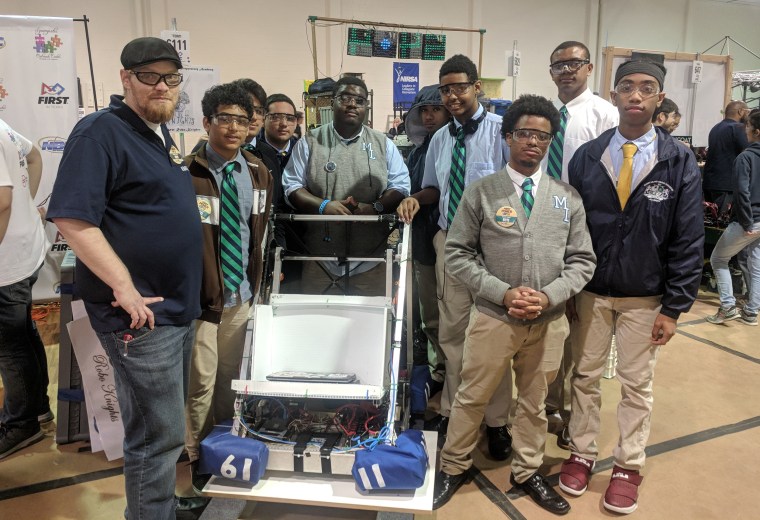

“We kinda didn’t have enough funds to get the stuff we needed and it kind of worried us,” said Ricardo Garcia, a sophomore and a robotics team captain at the Mickey Leland College Preparatory Academy for Young Men.

Business had been good for awhile, with the students eventually able purchase their slide. But sales soon slowed and the students began to realize that their efforts were limited.

“They were kind of lamenting, [saying] they have all of our donuts left,” said the school’s volunteer computer science teacher Andrew Ewert, recalling the day the group of students had come into his classroom disappointed that they still had several boxes of donuts in their hands.

Ewert had landed at the school in August through Microsoft’s Technology Education and Literacy in Schools (TEALS) program, an initiative that helps provide computer science education to high schools across the country.

Ewert, who works as a software developer for a startup called Vest, believes he had an easier time entering the field by growing up in a more affluent part of Houston.

“I went to one of those schools with massive, massive budgets for robotics,” Ewert, who has since started a GoFundMe campaign for the students, said. “And I was comparing it against them selling donuts and I was like, ‘They are never going to get anywhere selling donuts.’”

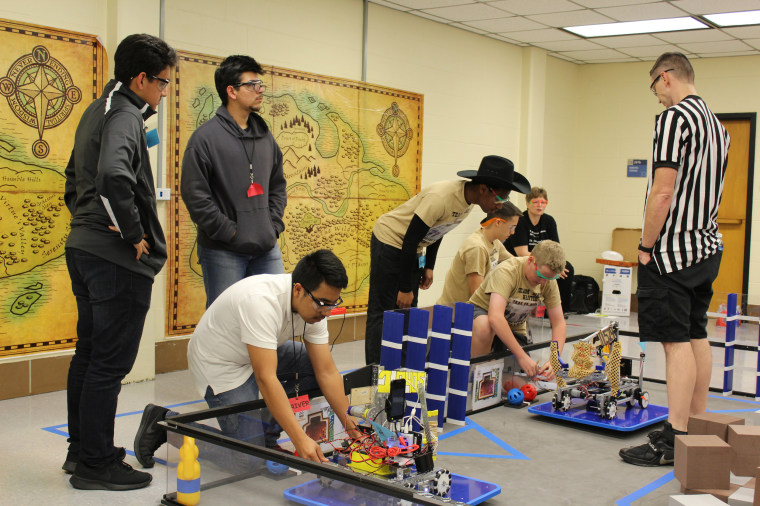

The robotics landscape in Texas has become an increasingly competitive one as the state now considers robotics as a University Interscholastic League (UIL) sport in partnership with FIRST robotics, a non-profit that supports science and technology learning among children.

The result has been an increase of schools in “underrepresented” and “underserved” areas, such as the Rio Grande Valley and Houston, growing their own robotics programs to compete across the state, according to FIRST Texas spokesperson Jennifer Navarrete. At the youngest level of robotics, ages 6-9, these regions made up close to 40 percent of the Texas team pool for the 2017-2018 season and contributed to an overall state growth of 94 percent from the previous season, according to FIRST.

Currently, FIRST has a team presence in close to 12 percent of U.S. schools and about 61,000 teams worldwide, according to stats provided by the organization.

“These teams are not just building robots they are doing so much more,” Navarrete said.“[They’re] operating much like a small business.”

And to compete, they have to.

A single season for high schools competing in the FIRST Robotics Competition can cost anywhere from $6,000 to $25,000, according to an expense reference form provided by the organization. And that’s not including the registration fees for events like the district state championship, which could add another $4,000 to the team’s bill.

The tasks asked of schools with FIRST robotics programs vary by age group. While elementary schools are asked to build robots out of LEGOS, those who participate at the top level in high school use professional graphical design software to build an "industrial-size" robot. At the top three levels of student robotics, teams are asked to program their robots to complete a set of tasks and face off against other schools in competitions.

But the costs add up and for many schools, including those in a district next to Mickey Leland, support from industry giants like BP and ExxonMobil can help a team afford the costs.

The Mickey Leland robotics team has yet to secure such support, mostly cultivating area partnerships that while important, according to the school’s robotics coach Paul Laforet. The result is a budget that pales in comparison to larger schools who can see budgets up to the “hundred of thousands,” according to FIRST Texas executive director and president Patrick Felty.

The Mickey Leland robotics team currently has at least $4,000 from the school and will be expected to raise the rest of the money for their team, according to principal Dameion Crooks. For the past three years, FIRST has also provided some relief to the school’s programs through grants, Laforet said.

Laforet acknowledges the need for additional sponsors and said he is looking at different ways to expand the group’s opportunities.

But there is at least one new measure he said he had to really think about implementing this year.

“This year is the first year that we are doing dues and to be honest, I have been sort of reluctant,” said Laforet, who says paying dues would have been cost-prohibitive to him as a kid.

Mickey Leland, which accepts students from various parts of Houston, has more than a 95 percent minority population and sees almost 75 percent of its students come from “economically disadvantaged” households, according to a 2016-2017 report on the school’s demographics.

“Just because you lived in poverty doesn't mean you have to dream in poverty,” said Crooks, who boasts his school’s STEM-focused curriculum and an MIT-bound former valedictorian. “You can actually dream and achieve and actually be successful in life.”

For students like Garcia, joining a robotics team in the U.S. had already been a dream come true.

“I had just moved to America and I had just seen a robotics team and it got me interested in it,” said Garcia, 15, who came to the country from Honduras in 5th grade.

A challenging first year for sure, Garcia said he had joined the Mickey Leland team in 7th grade with no knowledge about how to build a robot but began to appreciate the places his newfound hobby could take him.

“They told us we were going to Waco,” said Garcia, describing the first time he got to travel with a robotics team. “To think through something like robotics we could go to different cities was pretty eye opening for me.”

“It's hard to put into words,” said sophomore Jadi Martinez. “We all just work really well together. We know each other very well.”

Though the group has had their share of disagreements, mostly resulting from equipment malfunctions, Martinez said his relationship to his peers has ultimately pushed him to do better. And for the sophomore’s mother, that sometimes means enduring the almost hour-long commute to the school around 5 a.m on Saturdays.

“I’ve learned a lot about commitment,” the 16-year-old said. “There was a time when I really wasn’t contributing to the team. Even just showing up is doing something.”

All three students said they they are looking to pursue a career in STEM upon graduating and claim to have been inspired by the lessons they learned in and outside of the team’s building garage.

CORRECTION (Nov. 24, 2018, 10 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated Andrew Ewert's employer. He works for Vest, not Microsoft, but volunteers through Microsoft's TEALS program. It also misspelled the first name of the school principal. It is Dameion Crooks, not Damien.