MIAMI — One morning in 1977, Antonio Bascaro, a swashbuckling Cuban pilot who’d once trained with the CIA in an attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro, stopped inside a Little Havana jewelry store that served as a crossroads with the city’s criminal underworld.

The shop’s owner, a fellow Bay of Pigs exile, was a friend from their CIA days whose customers included some of the city’s flashiest drug dealers. One of them needed help checking up on boats he used to smuggle weed. The friend thought Bascaro, who’d flown reconnaissance missions for the Cuban navy, could help.

Later, over dinner, the young man, also a Cuban émigré but two decades younger, invited him to join their operation. “Do you have the guts to come with me?” Bascaro remembers the man asking him.

That is how Bascaro, a former military officer with a sterling service record, drifted into Miami’s booming marijuana economy and became a target in America’s escalating war on drugs. Arrested in 1980 and convicted of importing more than 600,000 pounds of Colombian marijuana into the southeastern United States, Bascaro has been behind bars ever since.

With 36 years of incarceration, he is now one of the longest-serving federal inmates doing time on marijuana charges. Everyone convicted with him, including the man who hired him, went free years ago; the one exception is a former co-defendant who is serving a life sentence for the shootings of two American drug agents in Colombia.

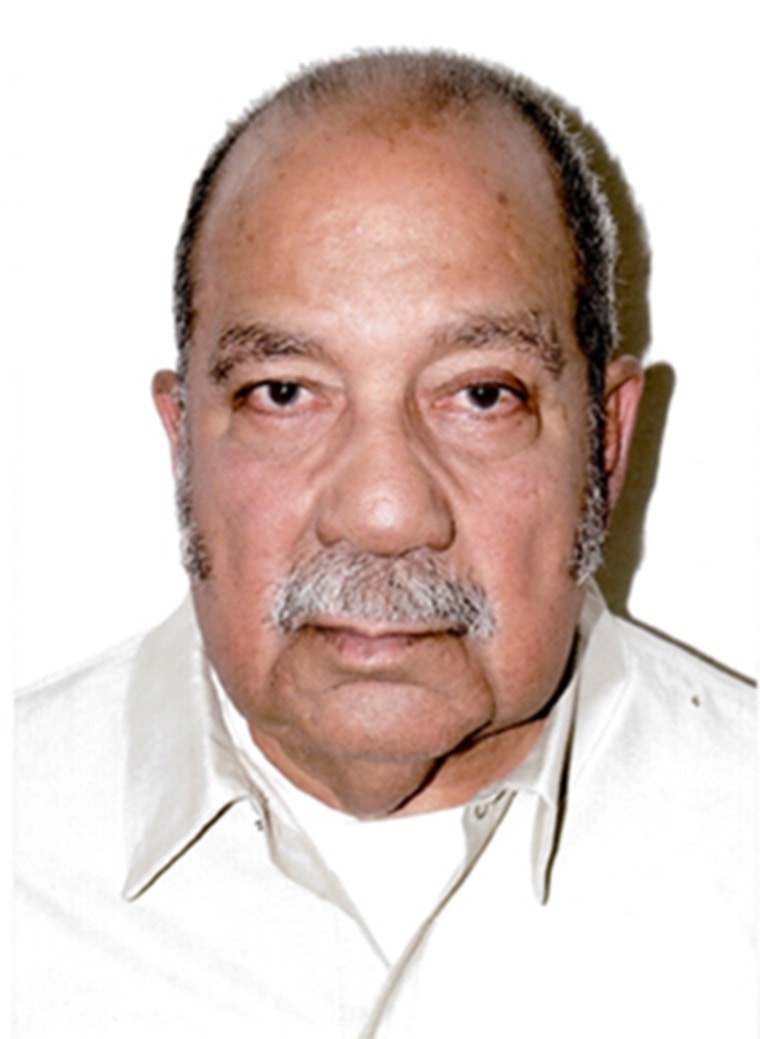

“I made a mistake and I’m still paying for it,” Bascaro, 81, said in an interview at Miami Federal Correctional Institution.

As the government rethinks laws that fueled an explosion in epic drug sentences, and President Obama offers clemency to hundreds of drug offenders serving long prison terms — and as marijuana has become a legal crop in some states — the decades-old smuggling case raises the question: Why is Antonio Bascaro still in jail?

Drug war relic

Bascaro’s story has gone unnoticed, in large part because he does not fit the typical profile of a war-on-drugs casualty. He was not a street-level dealer pulled into the business as a way to feed himself or his family or his drug addiction. He is not an American citizen.

But his case is revealing in other ways. It points to a dark period of recent American history, when the Cold War bled into the drug war, with Cuban exiles on either side. It recalls the early days of that drug war, before the explosion in violent crime and the rise of mandatory minimum sentences, when many politicians and policy makers favored decriminalization of marijuana. And it offers a glimpse into one of the government’s key tools in the drug war: persuading inmates to help build cases against other criminals in exchange for shortened sentences, while allowing those who declined such deals, even well-behaved prisoners like Bascaro, to grow old behind bars.

Bascaro’s one piece of good fortune is that he got busted before federal laws restricted the amount of good-time credit inmates could receive. He was sentenced to 60 years, but because he still falls under the old rules, he has earned a 2019 release date — meaning that he will, in the end, serve nearly 40.

Bascaro is afraid he won’t live that long, but his appeals and requests for leniency have failed in part because his case was too old to be covered under recent reforms. He’s also been repeatedly denied clemency. Obama’s program — which has commuted more sentences than that of his 11 predecessors combined — turned him down in August without explanation. Bascaro can apply again in a year, but it’s hard to imagine a different result.

And so he waits, sharing his story with anyone who’ll listen. Many, including some of his jailers, are left wondering: should an ailing old man, who has spent more than three decades in prison for a serious but nonviolent crime, be allowed to die behind bars?

Even the lawman who put him there isn’t sure.

Nickolas Geeker, who as U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Florida prosecuted Bascaro and dozens of others in a case known as Operation Sunburn, pointed out that the smugglers handled only marijuana, and not cocaine and heroin, drugs that drove a long wave of brutal violence in the 1980s and 1990s. Many cocaine and heroin offenders have received early freedom under Obama’s program, Geeker noted.

“With what the president has done with the sentences of other people dealing in more substantial, harder drugs than Bascaro was, why he would still be in there I really have no explanation,” Geeker said.

Costly code

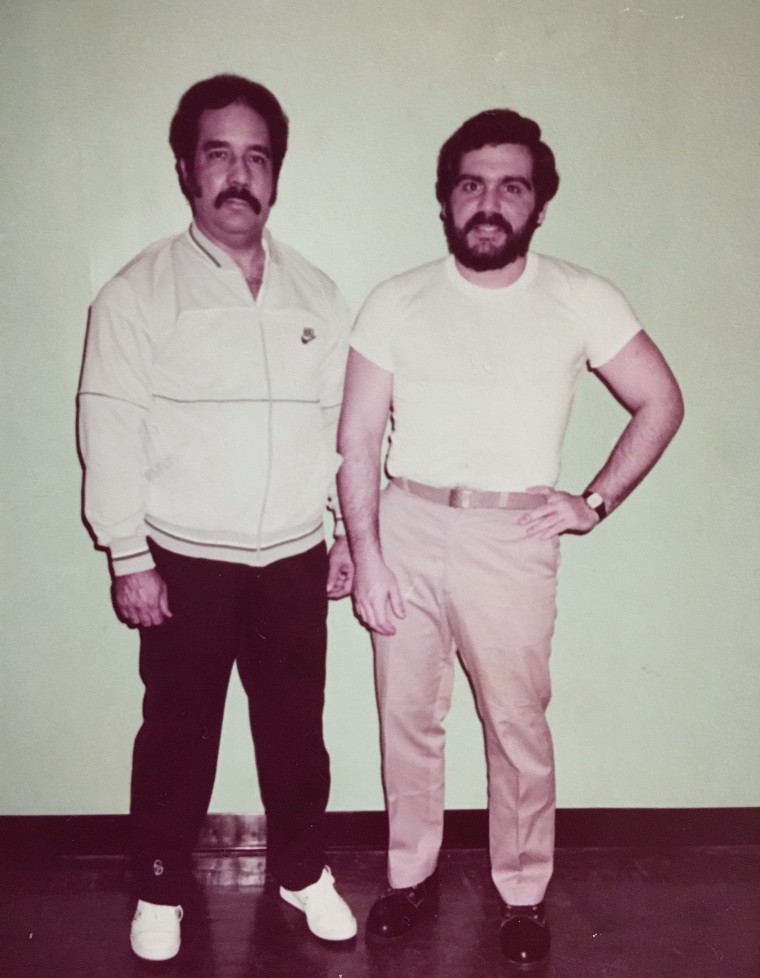

Jose Luis Acosta has an explanation. The charismatic young kingpin who recruited Bascaro was also sentenced to 60 years, but he got out in 1994 after serving a little more than 12. The reason, Acosta said, was that he cut deals with federal agents, offering them information on a number of other cases involving drug trafficking and police corruption, including one that targeted the jewelry store owner who introduced him to Bascaro. Prosecutors, in turn, persuaded judges to shorten his time in prison. He said he tried to get Bascaro to do the same, but his former partner refused.

“I’m very sorry he’s still in prison,” Acosta said. “He’s been in too long. I tried to get him to cooperate. But he lost his opportunity to do something for himself to get out of there.”

Mary Price, the general counsel of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, and an advocate for compassionate release of old and ailing federal prisoners, called Bascaro’s sentence “ridiculous” and faulted the federal criminal justice system for making him serve a quarter century more than someone who was just as guilty but became an informant.

“Is the fact that Mr. Bascaro didn’t cooperate worth 28 years? It’s not,” Price said. “Nothing justifies that difference.”

Bascaro said he does not regret refusing to testify or provide information against others. That, he said, would have broken an inviolable code that has guided him since his days as a young officer in the Cuban navy: don’t cross sides, no matter the cost. “I don’t believe in using anybody to be in a better position,” he said.

But he does lament the hole he’s left in the lives of his three children and 11 grandchildren. “I feel sorry for my family,” Bascaro said.

Aicha Bascaro, who was 12 when her father was imprisoned — and 24 when she next saw him, in a federal penitentiary in Pennsylvania — said she believed he was driven to drug smuggling by his desire to provide for his children after her parents divorced. As the decades passed, Aicha said, Bascaro became consumed with reuniting, ending every conversation and letter with the promise that they’d one day be together. When he turned 80, she quit her job to try to find a way to help him. She became his advocate, raising awareness of his case online and enlisting support of his old Bay of Pigs buddies.

“I know my dad did something, but whatever he did, he didn’t deserve to serve 36 years,” Aicha, 50, said.

Cuban hero

In person, Bascaro could pass as a harmless grandfather — his khaki prison uniform aside. He is wide and jowly, with thick sideburns and a handlebar mustache that hint at what passed as stylish the last time he was free. He gets around Miami FCI in a wheelchair or with a cane, wearing chunky orthopedic shoes and oversized shades. He complains of glaucoma, cataracts, debilitating back pain, skin ailments and sleep apnea — typical ailments for someone his age.

And he talks a lot about the glory days.

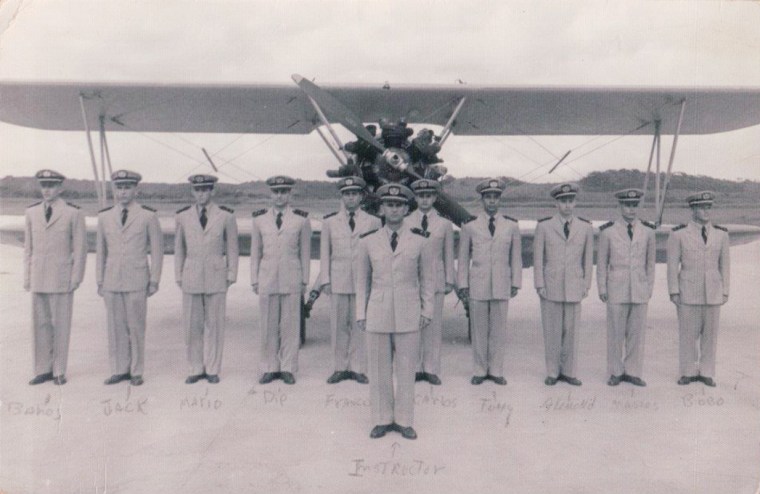

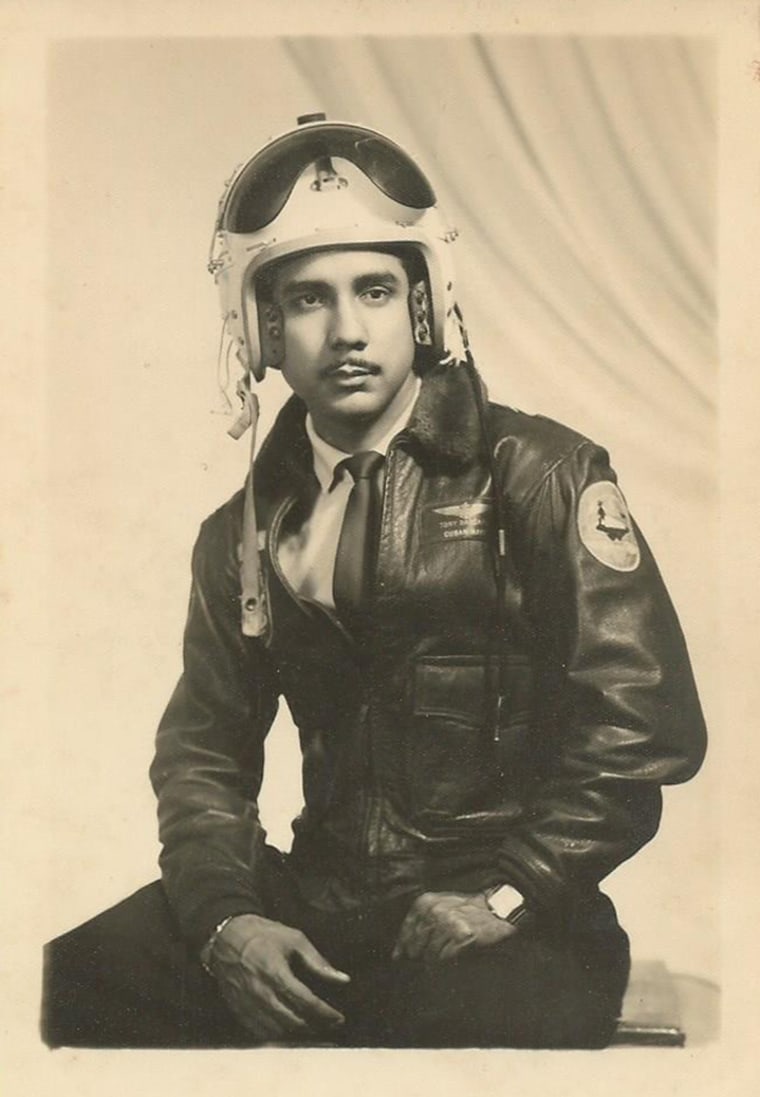

"I always wanted to fly," Bascaro said, recalling his decision as a young man to quit medical school and become a pilot in the Cuban Navy in 1952. “I like the emotion, the action.”

That was under the rule of Fulgencio Batista, the dictator who would be deposed by Castro’s communist rebels six years later. Bascaro and his fellow Navy airmen fought to repel them, taking reconnaissance photos of Castro’s training site in Mexico and supporting counter-intelligence operations when the rebels landed into Cuba in 1956 and set up a guerilla stronghold in the Sierra Maestra mountains.

Bascaro flew two rescue missions for government forces pinned inside, making a crash landing on the second. He said he was held in a hospital for more than a month, during which Castro’s brother, Raul, tried to recruit him to the rebel side. He said he told Raul Castro, “If you want to kill me, kill me, but I will not switch sides.” To this day, Bascaro said, he can’t understand why Raul Castro didn’t call his bluff.

After Fidel Castro took power and Batista fled the country in January 1959, Bascaro said he was held in various prisons, but was somehow spared from the mass executions of Batista officials. He said he was mistakenly released and then went into hiding before being granted asylum in Uruguay.

He traveled for a few months, eventually coming into contact with the CIA, which was recruiting former Cuban military members in a clandestine effort to topple Castro. He and the others were brought to Miami, where they were processed, paid and in February 1961 sent to Guatemala for training.

He and about 1,400 other recruits were stationed there until April 1961, when they moved to Nicaragua and launched the Bay of Pigs invasion. It failed in less than a day, before Bascaro’s fighter got off the ground. He and the others who remained were sent back to Miami, but instead of waiting for instructions from the CIA, he said he returned to Guatemala, where he’d fallen in love with a local woman whose uncle was a top federal government official. They married, and he found work, first flying crop-dusting planes, and later as a pilot for tourist companies and wealthy businessmen. His Bay of Pigs contacts in Miami invited him to join them for other covert operations, but he declined, telling them to let him know if they ever planned to take back Cuba.

He kept in touch with some of them, including Guillermo Tabraue, who’d served as the exiles’ liaison with the CIA and was now the owner of a thriving Little Havana jewelry store. By 1977, Miami had become the drug capital of the Western Hemisphere, a hub for smugglers and money launderers. Many drug dealers — and city cops — shopped at the store. (Tabraue was later accused of trafficking himself, but the case fell apart when he was revealed as a government informant paid to provide information on former Bay of Pigs veterans who’d gone into the drug business).

By then, Bascaro had divorced. He wanted to do more to help his children financially. That is why, he said, he welcomed the introduction with Acosta, who was looking for a pilot to help keep tabs on his fleet of vessels and help scout places to offload bales of weed on the Florida coast. The prospect gave him a thrill that he hadn’t felt in years. “I felt my adrenaline going,” he recalled.

The hero's fall

In some parts of Florida, marijuana smuggling, which was largely free of violence, had become a way of life, turning fishermen, pilots and truckers into wealthy outlaws — and enriching bankers and local law enforcement authorities who chose to look the other way. Bascaro was among several Bay of Pigs veterans who found their past experience as clandestine operatives useful.

“It was exciting,” Bascaro recalled. “I wasn’t fighting in the war, but it was something similar.” The money was also good — about $30,000 for a few hours’ work.

Acosta’s operation brought together a motley assortment of players that included Colombian suppliers, Cuban emigres, rural haulers, corrupt lawyers and a suntan lotion distributor. Bascaro says he never actually touched any of the marijuana, sticking mainly to logistics, and occasionally observing the unloading of shipments. He estimates he made between $750,000 to $1 million over two years.

He and Acosta became close — like a father and son, they both say — and Bascaro persuaded the younger man to move to Guatemala, where they started legitimate side businesses together. Bascaro bought a ranch in Guatemala and a home in Miami, where he brought his children during school vacations. He partied, too, but generally tried to avoid the outlandish behavior that had come to define Miami’s exploding drug scene. “No drink or drugs,” he said. “I just liked good food and good women.”

Authorities got tipped to the Acosta organization in 1978, after one of the shrimp boats it used to ferry loads into the Gulf of Mexico ran aground. Investigators tapped the smugglers’ phones and tracked their shipments to Florida and Georgia. In February 1980, Bascaro was taken into custody in Guatemala and sent to Georgia, where he was convicted of marijuana possession. He was then sent to Florida, where he refused offers of immunity from further prosecution if he’d tell a grand jury about the group’s operations. Other members did, however, and Bascaro, Acosta and several others were convicted of operating a massive criminal enterprise.

Bascaro remained resolute in his stand against helping authorities. He declined to parlay his smuggling connections, and declined to serve as a witness when he saw wrongdoing behind bars, an act of self-preservation that aligned with his moral stand, he said.

Gradually, his former co-defendants started getting released after serving fractions of their sentences. That included another Bay of Pigs-era exile who was sentenced to 40 years but escaped while on furlough helping U.S. agents ensnare Cuban officials suspected of trafficking cocaine. He was recaptured four years later, and was released in 2002.

Bascaro focused on less compromising routes out of prison. He amassed good-behavior credits and tried repeatedly to appeal the length of his sentence. He applied for compassionate release, due to his age, and was denied. That left clemency as his only option. He filed twice on his own, and this summer got volunteer assistance from a lawyer working for a program aimed at processing the massive number of applications to Obama’s clemency initiative. That, too, failed.

He began to wonder if there was something in his files he didn’t know about, a black mark that doomed his petitions.

Bascaro's hope turned to desperation. After completing just about every education and vocational program available to him, he says he now spends his days reading, listening to music and corresponding with anyone who’ll listen to his story. He keeps in touch with some of his old friends from the Bay of Pigs, but not Acosta, saying he still holds a grudge related to a fight while they were incarcerated together in Pennsylvania in the early 1980s.

Acosta, for his part, says he no longer harbors any resentment against his old friend.

“That was a long time ago,” Acosta, 60, said from his home near Miami. “I don’t hate him. I’m here to help him if I can in any way to get out of there. Because even though we did some things we weren’t supposed to do, I remember a lot of good times together. And we’re getting old.”

Bascaro’s only goal now is to live long enough to have that long-promised reunion with his children, and live in the United States as a free man.

“I hope I’ve got enough health and life to do that time and go back to my family,” he said.