In October 2011, a doctor from the north side of Chicago heard news that authorities were trying to identify the last of the unnamed victims of 1970s serial killer John Wayne Gacy. She immediately thought of her half-brother.

Andre Drath, a troubled child, had been forced into the Illinois child-welfare system in 1976, when he was 14, and disappeared two years later. The lonely, vulnerable boy, who went by Andy, was just the kind of kid Gacy preyed on.

The sister, Willa Wertheimer, called the Cook County Sheriff's Office and left a message.

The call marked her first step in a journey that culminated this month with a stunning answer to her brother’s fate — and the start of another mystery 2,000 miles away.

Wertheimer was among dozens of people who flooded the Sheriff's Office hotline in the first few weeks after the Cook County Sheriff's Office anounced it was trying to identify eight boys and young men whose remains were found in a crawlspace in Gacy's home. The office invited families who thought their missing loved ones could have been murdered by Gacy to provide DNA samples that could be compared with the victims'.

Many of the tips were long shots, but Wertheimer's story struck Detective Jason Moran as a potential sure thing. He took a DNA sample from Wertheimer, 51, who had the same mother as Drath, and waited to see whether her genetic profile matched any of those taken from the victims.

There was no hit. But Wertheimer's DNA went into a national database, where it would be compared with millions of other samples in the system, just in case.

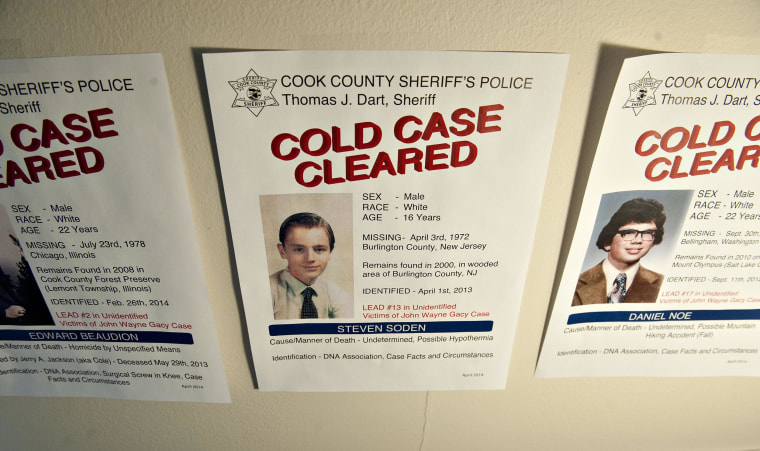

Years passed. Moran kept following tips. Only one led to the identification of an unnamed Gacy victim. But others took the detective on unexpected paths. He found former missing persons who were still alive, others who had died of natural causes, and three who had died under suspicious or unexplained circumstances.

The investigation has inadvertently illuminated America's historically poor handling of missing-persons cases and the country's slipshod system of tracking the unidentified dead — a crisis that the National Institute of Justice has called a "silent mass disaster." Tens of thousands of people vanish every year, and an estimated 40,000 sets of human remains have gone unidentified. A fraction of those specimens have been entered into federal crime-information databases.

The search for Gacy's victims is now a case study on the power of DNA to bridge those gaps: If more law enforcement agencies collected DNA from unidentified bodies and took DNA from the families of missing people, there is no telling how many cases could be solved.

"We'd be lying if we said we expected this," Cook County Sheriff Thomas Dart said. "This is something that should reinforce that anybody who has a missing person-related issue, if it's someone they're related to, should give DNA."

Related: The Lost and the Dead: How John Wayne Gacy Led a Family to its Missing Son

While Moran chased leads in the Gacy investigation, a state laboratory in California was working through a backlog of specimens submitted by the San Francisco Medical Examiner's Office for DNA analysis. One came from a teen boy who, according to the autopsy report, was found shot to death and buried in the sand on Ocean Beach in June 1979 without any identification on him, a case that quickly went cold. Included in the report was a note that the victim had several tattoos, including one that said "Andy."

The lab submitted the boy's DNA into a national database in late 2014.

In May, a technician at the University of North Texas Center for Human Identification alerted Moran that there had been a match in the national database with one of the profiles from his Gacy investigation. Elements of Wertheimer's DNA were similar to those taken from the body of an unidentified young man in San Francisco, labeled John Doe No. 89.

The similarities did not necessarily mean the body was Wertheimer's half brother. So Moran reviewed the original report from the San Francisco Medical Examiner's Office, and read through Drath's juvenile records, where he pieced together the boy's life story.

Drath was raised by a single mother, who later married and gave birth to Wertheimer, four years younger. Their mother died when they were young, and her father became the children's sole guardian. But Drath had behavioral problems, and his stepfather handed custody to the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. While Wertheimer remained with her father, Drath spent his teens in and out of foster homes and juvenile detention facilities, frequently running away. He told counselors about his desire to live in San Francisco, and his case file showed that he indeed fled there in late 1978 or early 1979, at the age of 16. He found a lawyer to represent him in an attempt to remain in California.

Moran closed the file and knew he'd connected Drath's disappearance to the murder in San Francisco. The San Francisco Medical Examiner's Office agreed, and amended the death certificate to include Drath's name.

Two weeks ago, Moran called Wertheimer in for a meeting. He waited until they were face to face to tell her he'd found Andy. She seemed torn: happy to know what happened to her brother, but sad to know he died violently and alone, weeks before his 17th birthday.

It was troubling to think of how easily Drath's disappearance had fallen through the cracks of a broken system — his unstable home life, his unsupervised arrival in California, his forgotten death, the delayed processing of his remains — and how arbitrarily the pieces had come together. If not for Dart's Gacy investigation, if not for Wertheimer's perseverance, if not for Moran's gumshoe work, the case could have easily gone unsolved.

Today, Wertheimer urges other families with missing relatives to submit their DNA to the national missing persons database.

"You should never lose hope in finding your loved one," she said in a statement distributed by the Cook County Sheriff's Office as part of a Wednesday announcement of the Drath case's resolution. "He could still be living, or at least your heart can know the peace of bringing him home."

She is now making plans to return Drath's body, which was buried years ago in Colma, California.

Meanwhile, San Francisco police have reopened the murder case. Knowing who the victim was opens up the possibility for many new leads.

And the Cook County Sheriff's Office is still running down tips left on its Gacy hotline, hoping to give names to seven victims whose remains were found in the serial killer's home, bodies no one has claimed.