It was supposed to be a "slam-dunk."

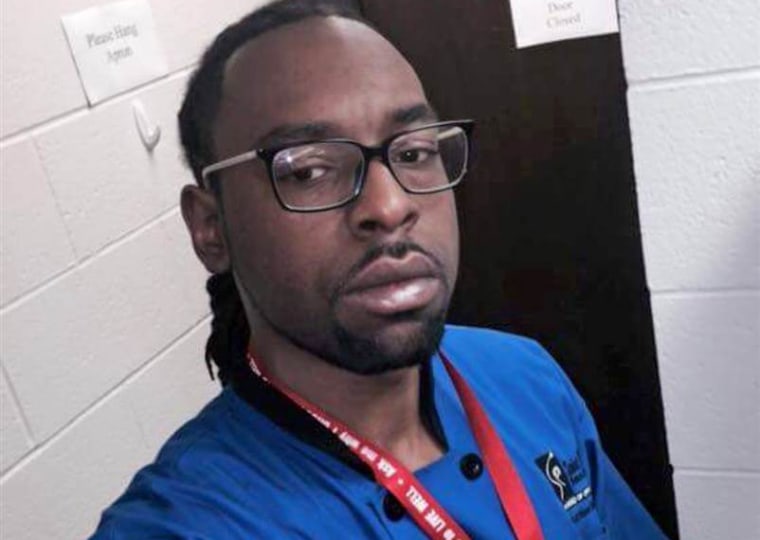

Prosecutors seemed hopeful Ray Tensing, the University of Cincinnati police officer who shot and killed Samuel DuBose, an unarmed motorist, would be convicted of manslaughter. Tensing was also charged with murder.

But for jurors, the facts of the July 2015 shooting were apparently less clear-cut. After five days of deliberation, the jury said Friday it was deadlocked. A judge declared a mistrial for the second time.

It is rare, and extremely difficult, to convict a law enforcement officer after a fatal shooting, according to criminal justice experts who spoke to NBC News on Monday.

That was the lesson of at least two other high-profile police shooting trials in the last two weeks.

Related: What to Know in Case Against Cincinnati Cop

In Minnesota, former officer Jeronimo Yanez was found not guilty of second-degree manslaughter and other charges in the July 2016 killing of Philando Castile. In Wisconsin, former officer Dominique Heaggan-Brown was found not guilty of first-degree reckless homicide in the August 2016 killing of Sylville Smith.

For legal scholars and criminologists who study law enforcement, those outcomes are not exactly surprising.

"We often see that jurors are reluctant to second-guess the split-second life-or-death decisions of a police officer in a potentially violent street encounter," said Philip Stinson, an associate professor of criminal justice at Bowling Green State University.

Cops are held to a different standard

The law, generally speaking, is on the side of the cops, who have wide latitude when it comes to using force, according to David A. Harris, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law who teaches in police behavior.

A pair of court cases laid the foundation. The U.S. Supreme Court, in Tennessee v. Garner in 1985, ruled that an officer can use deadly force against a fleeing suspect if they believe they are in danger of death or serious physical harm.

Four years later, the Supreme Court ruled in Graham v. Connor that officers who use force must be judged on a standard of "objective reasonableness."

"For better or worse, whether you believe in it or not, [the law] is very favorable to police use of force," Harris said. "That objective standard is very wide in terms of giving police discretion."

Tensing, Yanez and Heaggan-Brown all said they feared for their life during their fatal encounters, all of which were captured on camera, sparked protests, and reignited national fury over police brutality.

Many civil rights advocates and plaintiffs attorneys say the laws governing use of force give the police far too much latitude to claim they feared for their lives.

Police often "conjure up something in their mind that's not a real danger," said attorney Benjamin Crump, who has represented the families of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown.

Two of the high-profile recent cases hinged on questions of reasonable fear:

- Tensing, the Cincinnati officer, said he feared DuBose, the motorist he pulled over for a missing front license plate, would use his car to kill him. Prosecutors said the car was not moving until about one second before Tensing shot DuBose.

- Yanez, the former St. Anthony, Minnesota, officer, testified that Castile, the cafeteria worker he pulled over, ignored the officer's commands not to pull out his gun. Castile, who had a permit for his weapon, had told Yanez he was armed. In squad-car video of the shooting, Castile can be heard saying, "I'm not pulling it out" and, right before he died, "I wasn't reaching..."

In the last 12 years, 82 state and local police officers have been charged with murder or manslaughter in an on-duty shooting, according to data compiled by Stinson, the Bowling Green associate professor, who tracks police crime.

Of those officers charged since 2005, the year Stinson began collecting data, 29 were convicted and 34 were not.

The bias in virtually all of us

The wider social issue, according to Crump and other civil rights advocates, is implicit racial bias — the idea that every person holds subconscious prejudices — even those in positions of supposed impartiality, such as judges.

Related: Can ‘Implicit Bias’ Training Stop Police Officers From Acting on Hidden Prejudice?

"We need to look at implicit racial bias as an issue not just for officers [involved in on-duty shootings] but for jurors, too," said Kami Chavis, the director of a criminal justice program at Wake Forest University School of Law.

DuBose, Castile and Smith were black; Tensing is white, Yanez is Latino and Heaggan-Brown is black.

The case around the killing of Castile, in particular, highlights the issue of implicit bias and how negative stereotypes about black men affect cops and juries, according to Vanita Gupta, the former head of the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division.

Castile, she said, "was trying to comply" with Yanez. Castile had been stopped numerous times so "he knew what to do and what to say to a police officer."

But the jury, Gupta said, was not "willing to second-guess the officer" — despite the account of Castile's girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, who live-streamed the incident on Facebook.

Related: Castile Family Reaches $3 Million Settlement in His Death

What's more, some jurors come to court with a "dominant narrative that says police are the good guys," Harris said.

"We know that's not always true, of course," Harris added. "But persuading jurors that the police have committed a crime, and not just made a mistake, goes against that narrative. It's a very steep hill for prosecutors to climb."