Attorney General Jeff Sessions just made it easier for police to seize cash and property from people suspected ─ but not necessarily charged with or convicted ─ of crimes.

He did it by eliminating an Obama administration directive that prevented local law enforcement from circumventing state restrictions on forfeiture of civil assets. The technique was embraced in the early years of the war on drugs, but it has since been linked to civil rights abuses: people losing cash, cars and homes without any proven link to illegal activity; police taking cash in exchange for not locking suspects up; a legal system that makes it hard for victims to get their possessions back.

Two dozen states have made it harder for authorities to take property from suspects without first securing criminal convictions. Three have outlawed it entirely, according to the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit that advocates for reform.

Local police got around those laws by asking federal agencies, such as the Drug Enforcement Administration, to take on forfeiture cases and then share the proceeds. That loophole, called "adoption," helped fuel an explosion in forfeitures, which became a multibillion-dollar government enterprise.

One of Sessions' predecessors, Eric Holder, issued a directive in January 2015 that prohibited the adopted forfeitures, which led to a drop in seizures. Police and prosecutors, who used the money to pay for new cars, equipment and training ─ and to help crime victims ─ hated it. They made it a key complaint to the Trump administration.

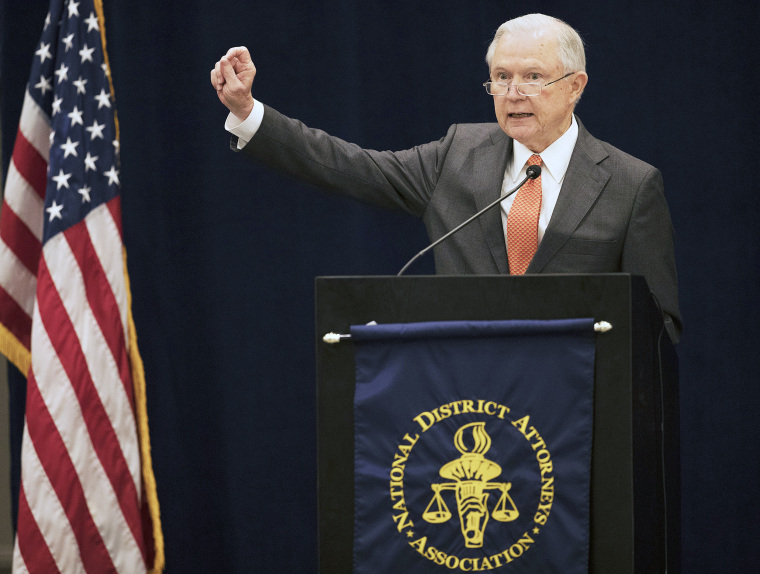

They found a sympathetic ear with Sessions, a former federal prosecutor and Republican senator from Alabama who has called for a return to 1980s-era crime-fighting strategies in defiance of a bipartisan movement to ease up in favor of rehabilitation and treatment. Sessions has already reversed a Holder memo that sought to curb the use of mandatory minimum prison sentences.

Related: Under Sessions' Plan, Government Will Seize More People's Property

On Wednesday, Sessions tossed out Holder's directive on adopted forfeitures, adding some restrictions aimed at protecting innocent people.

"It weakens the criminal organizations when you take their money, and it strengthens our law enforcement when we can share it together and use it to further our effort against crime," Sessions said at a meeting with police and prosecutors in Washington.

But experts in criminal asset forfeiture said Sessions' safeguards ─ increasing federal prosecutors' scrutiny of adopted forfeitures and setting a minimum dollar amount for each ─ would not fix a system that gives authorities a financial incentive to pursue certain kinds of cases, even if they aren't strong enough to prove in court.

A March report by the Justice Department's Office of Inspector General sharply criticized the federal government's use of civil asset forfeitures, saying it didn't keep good enough records to determine whether seizures actually helped criminal investigations or whether they violated people's civil liberties.

"The notion of eating what you kill, as we call it, is terrible public policy," said J. Scott Gilbert, a Mississippi lawyer and former federal prosecutor who used to manage an asset forfeiture program for U.S. attorney's offices. "The vestiges of paying judges by the conviction or the police officer by arrests went away a long time ago. This is the only such thing left."

In some cases, federal agencies depend on deputized police officers to investigate cases for them, and forfeiture money is often the only way to entice them to maintain the partnership, Gilbert said.

The answer, he said, is to implement a grant program that would separate prosecution decisions from funding.

In his meeting with law enforcement groups on Wednesday, Sessions downplayed claims that civil asset forfeitures preyed on the innocent, citing research that showed 4 out of 5 people who had property taken from them didn't fight it in court.

"They're not challenging it because usually this was drug money, they know it's drug money, and they have no basis to contest the forfeitures," Sessions said.

Experts don't dispute that statistic. But they say it's not because the targets are guilty; it's because, in civil forfeitures proceedings, people who can't afford lawyers or don't understand the system find it almost impossible to fight the government.

"Is it true that they are really guilty of something? The facts don't support that," said Louis Rulli, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School who advocates for equal justice for the poor.

Session's directive, Rulli said, "is going in the opposite direction of where the states are going in trying to reform civil asset forfeiture. It's an attack on federalism, taking over states' choices on how best to combat crime and to protect the property of their citizens."

Government overreach is one basis on which conservative members of Sessions' own party ─ including some who have sponsored bills in Congress to curtail civil asset forfeiture ─ have denounced the move.

Critics also say civil forfeitures breach constitutional rights of due process and protections against taking property without just cause.

Changing the law is the only way to effectively curtail abuses, said Derek Cohen, deputy director of Right on Crime, a conservative organization that advocates for criminal justice reform.

Sessions' memo, Cohen said, makes things a little better than they were before Holder's memo. But it's not enough to leave it to Justice Department lawyers to decide what's worth seizing, he said.

"Prosecutorial discretion, and executive discretion, is not a substitute for sound policy," Cohen said.

Trevor Burrus, a research fellow at the Cato Institute's Center for Constitutional Studies, agreed.

"You can't expect the cops and attorneys to be proactive in trying to root this out, partially because they benefit from it," Burrus said. "They use it to buy police cars and things like that. The incentives aren't there in rooting out injustice."

Darpana Sheth, senior attorney at the Institute for Justice, said the best option is "to abolish civil forfeitures altogether" and leave it to criminal cases, in which the government needs to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone broke the law.