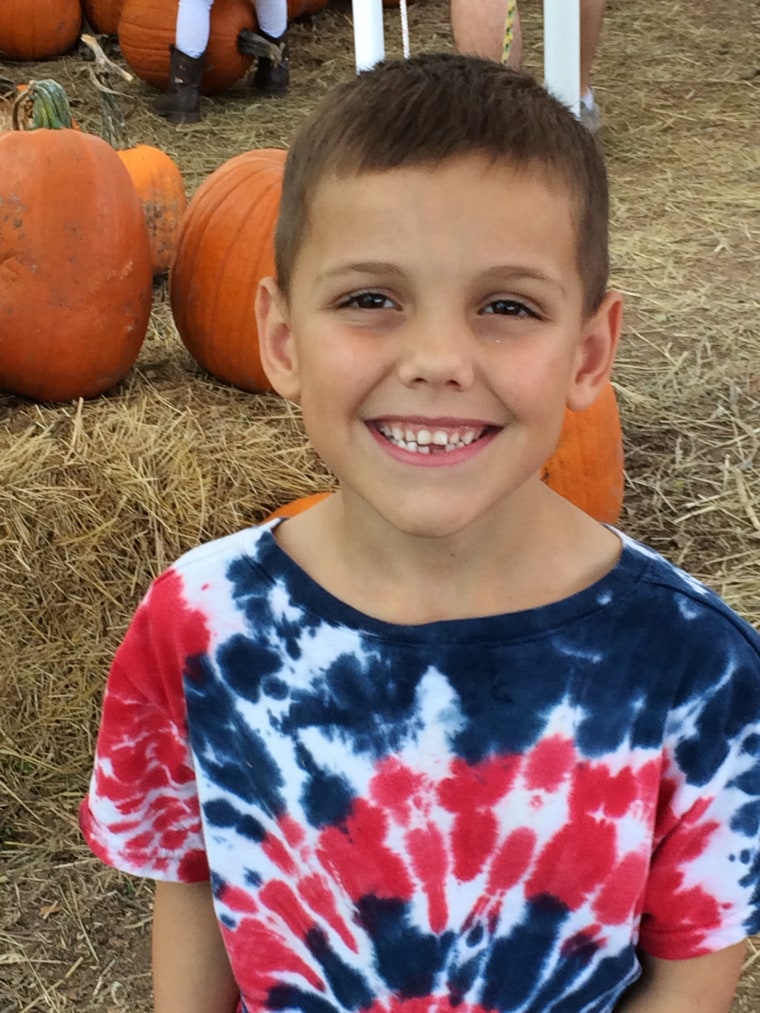

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — School isn’t usually tough for Kalyb Wiley-Primm, a smart, soft-spoken kid who likes science and robotics.

But one day in second grade, Kalyb said, some bullies made it a nightmare. Upset by the bullies’ taunts, he began to cry and yell. "I was like, ‘I didn’t do anything to you!’" he recalled.

When a school security officer at George Melcher Elementary found Kalyb crying and screaming in the classroom, he asked Kalyb to come with him. Out in the hallway, Kalyb, still crying, refused to follow the officer.

According to the incident report, the officer told Kalyb to "calm down" and tried to assure him "he wasn't in trouble," but for Kalyb, it didn't feel that way.

"It was not okay," Kalyb, now 10 years old, said. "I was very mad."

Kalyb kept trying to walk away from the officer, and got more upset the farther they walked. The officer then handcuffed the 50-pound, four-foot boy and marched him to the principal’s office. According to the incident report, the officer said he cuffed the boy, who "appeared to be out of control," to keep him from hurting himself.

Due in part to tragic school shootings like the Columbine massacre, police and security officers are now a regular presence at schools. But the handcuffing of Kalyb Wiley-Primm is one of many incidents across the country that have led to calls to examine the role that police play in schools, and change how discipline is meted out — particularly to minority students and students with disabilities.

How Does Your School District Compare? Click Here to Find Out

The NBC News Investigative Unit and the NBC-owned stations analyzed data collected from all public schools in the nation by the U.S. Department of Education. Called the Civil Rights Data Collection, every two years all public school districts are required to report to the Education Department on wide-ranging topics from suspensions and expulsions to arrests and referrals of students to law enforcement. Districts are also required to break down data by race and disability.

NBC News crunched the numbers from the 2013-2014 school year, the most recent data available. The analysis found that nationally, black students, like Kalyb, and students with disabilities are suspended, expelled, arrested and referred to police at rates disproportionately higher than their white and non-disabled peers.

Related: Data Reveals Role of Race in Policing New York's Schools

Examinations of police and court records also found that law enforcement became involved with students for minor discipline issues.

"Certain kids get counseling," said Illinois State Senator Toi Hutchinson, who successfully introduced a bill in the legislature requiring the state Board of Education to make discipline data public. It also requires districts to address significant disparities in discipline. "Certain kids get wraparound services. Other kids get juvenile detention."

"I think what you’re seeing is data across the country to say that instances like [these] are not anomalies," Hutchinson added.

'We Don't Want to Arrest. We're Here for Safety'

Forty-three percent of public schools in the United States now have some kind of security personnel present at school at least once a week. Districts employ school resource officers with a variety of backgrounds — sometimes off-duty or retired police officers. Districts also employ school security personnel who are not sworn law enforcement officers, like the one who handcuffed Kalyb Wiley-Primm.

Holly Zornes, who works at a high school not far from Kalyb’s school in Kansas City, is a police officer. She patrols the halls in a bulletproof vest, carrying cuffs and a loaded gun.

However, she says her mission is not to arrest students. "We as police officers don’t want to handcuff a child," she said, "We don’t want to arrest. We’re here for safety."

Dr. Mark Bedell, the new superintendent of Kansas City Public Schools, says the presence of police in schools is vital.

"We know a lot of terrible things have been happening in schools around the country with people just intruding. And we've had mass shootings."

Bedell, who was not working in Kansas City at the time of Kalyb's incident, says that some districts have used officers to do the jobs of principals and assistant principals in enforcing discipline. The key, he says, is clearly defining the officers’ role.

Said Bedell, "Their job is to ensure that we have a safe learning environment, and that our kids are protected from imminent harm. Period."

Last fall, then-Education Secretary John King, Jr. posted a letter on-line emphasizing that point, reminding school districts that school resource officers should have "no role in administering school discipline."

Currently, the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights has over 450 open investigations for discrimination on the basis of race, sex, disability and national origin in the administration of discipline in schools.

"I am concerned about the potential for violations of students’ civil rights and unnecessary citations or arrests of students in schools, all of which can lead to the unnecessary and harmful introduction of children and young adults into a school-to-prison pipeline," King wrote.

Once a child enters the juvenile justice system, said Diane Smith Howard, senior staff attorney at the National Disability Rights Network, an advocacy group for people with disabilities, their image of themselves starts to change. "Kids start to identify. ‘I’m a criminal. I’m a delinquent.’ It sends a really strong message that you don’t belong here at school."

{

"ecommerceEnabled": false

}During the 2013-2014 school year, schools reported 65,150 school-based arrests of students. Students were referred to law enforcement more than 200,000 times. The Education Department defines a "referral" as anytime a student is reported to any law enforcement agency or official for a school-based incident, regardless of whether official action is taken.

Click Here to See the Statistics for Your School District

NBC News’ analysis found that the presence of law enforcement on campus makes it more likely that a student will be arrested or referred to police. Nationally, schools with officers are 2.51 times more likely to refer students to law enforcement, compared to schools without officers. Schools with officers are 3.12 times more likely to arrest students compared to schools without officers.

According to the data, nationally:

· Black students are 2.9 times more likely to be arrested while at school than all non-black students;

· Black students without a disability are 3.49 times more likely to be arrested at school than white students without a disability;

· Black students without a disability are 2.25 times more likely to be referred to law enforcement while at school than white students without a disability;

· Students with disabilities are 2.96 times more likely to be arrested while at school than students without disabilities;

· Students with disabilities are 2.91 times more likely to be referred to law enforcement while at school than students without disabilities;

· Black students with disabilities are 2.80 times more likely to be arrested while at school than white students with disabilities;

'It Was Heartbreaking'

Lisa Caruso, 37, remembers when the principal at Pirtle Elementary in Belton, Texas, told her that the school resource officer handcuffed her eight-year-old son, Ethan.

"You kind of feel like everything falls away," she said. "It just kind of drains you. You handcuffed an eight-year-old?"

Ethan, who is white, was diagnosed with ADHD when he was four. He has trouble controlling his impulses and gets frustrated easily. As a student served under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, a federal law that protects the rights of public school children with disabilities, Ethan has an education plan. Medication helped him in school, but when he got frustrated, teachers were instructed to allow him to take a break and calm down, or redirect him to other activities.

Last year, Caruso and her husband were called to school after an incident that began in the lunchroom. Ethan, who has a peanut allergy, said other students began pushing a tray they said was covered in peanut butter over to him. Surveillance video of the lunchroom shows Ethan pushing the tray away from him and lifting up a chair. A lunch aide temporarily restrained Ethan, and then picked him up and carried him out of the lunchroom.

"I don't wanna go to jail."

Body-cam footage revealed what happened next. Administrators called the school resource officer, and Ethan was handcuffed. In the video, administrators say that Ethan threw books and chairs.

At one point, the school’s principal told Ethan, "Stop struggling," and asked the officer, "Are you sure you aren’t going to get in trouble for this?"

Ethan whimpered, "I don’t wanna go to jail."

Click Here to See How Your State Treats Kids By Race and Disability

"I will never forget," Lisa said, fighting back tears, of the moment she came to school and saw Ethan on the floor of a schoolroom with an officer standing over him. "I sure won’t. He was huddled in the corner like an animal."

According to an NBC analysis of the federal data, students with disabilities are 23 times more likely than their non-disabled peers to be subjected to mechanical restraint.

{

"ecommerceEnabled": false

}"It’s not and it has never been our policy to call law enforcement to deal with an unruly elementary student," said Kyle DeBeer, communications director for the Belton Independent School District. "Our training provides principals and assistant principals with multiple de-escalation strategies. It appears those strategies weren’t utilized before calling the officer in this case."

Last year the school resource officer involved in the incident was reassigned and the superintendent of the district apologized to the family.

A Carton of Milk

NBC News found that students have been charged with crimes like assault for getting frustrated and pushing past a teacher, or battery for getting in a schoolyard fight.

Or in the case of 15-year-old Ryan Turk, theft for taking a 65-cent carton of milk from the cafeteria.

When Ryan, who went to Graham Park Middle School in Prince William County, Virginia, was in the eighth grade, he forgot to grab milk when going through the lunch line. Ryan, whose mother says he was enrolled in the free lunch program, went back to get it.

Watching Ryan, the police officer assigned to the school thought he had stolen the milk. The officer confronted Ryan and asked him to go to the principal’s office. When the middle-schooler resisted, the officer handcuffed him and later charged with him with petit larceny and disorderly conduct.

Click Here to See How Arrests, Expulsions and Corporal Punishment Differ Across the U.S.

Ryan, who is black, was suspended and forced to go to court. This past January the prosecutor ultimately declined to press charges, but retains the right to bring back charges for one year.

"I think the whole situation was handled wrong," Ryan’s mother Shamise said, adding that her son now has trouble trusting authority figures. "The principal, she should’ve been the one addressing the situation, not the officer."

A spokesperson for Prince William County Schools said, "Confidentiality requirements prevent us from commenting on disciplinary actions taken by PWCS or non-PWCS law enforcement officials with respect to any specific student."

He also said that discipline is determined by evaluating a student’s overall actions against the county schools’ Code of Behavior, and that "any police action and/or legal charges are determined independently by the police."

"We don’t want to add to the school-to-prison pipeline."

Ryan Turk’s case is one of dozens of cases NBC News found around the country of students facing juvenile charges for the kind of behavior that would have resulted in detentions or notes home in years past.

In Louisiana, an eighth-grader was handcuffed and dragged out of class for throwing Skittles at another student on the bus. In South Carolina, a teen was arrested, charged and convicted of disorderly conduct for cursing and causing a scene in the library.

Officials in Louisiana did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Officials from the South Carolina school district noted that the district was not named in a lawsuit linked to the incident, but declined to comment on the suit and did not comment on the incident.

{

"ecommerceEnabled": false

}Records requests sent by NBC News to more than a dozen districts and police departments across the country found that while school resource officers deal with serious incidents such as students bringing firearms to school or possessing drugs, they also file charges against students for what seem like minor discipline issues.

In Topeka, Kansas an officer referred a student who stole a $5 can of Kool-Aid to the district attorney. In Savannah, Georgia an elementary school student was arrested for "disrupting public schools," a catch-all law that criminalizes behaviors that disrupt the school environment.

More than 20 states have some kind of "disturbing schools" law on the books. In New Mexico, a 13-year-old Hispanic student was arrested in 2011 and charged with "Interference with the Educational Process" for fake burping in gym class, a case attorneys have petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to consider.

Chief Ron Brown, director of school safety for Topeka Public Schools Police, said the Kool-Aid theft wasn’t ultimately prosecuted and that he directs his officers to exercise discretion. "This is not about putting kids in jail," he said. "It’s about ensuring justice. A lot of times school administrative remedies are sufficient."

"We don’t want to add to the school-to-prison pipeline," he added.

Officials in Savannah did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

In New Mexico, the arresting officer was called to the class by the teacher. In subsequent rulings, lower courts dismissed complaints filed by the boy’s mother against the officer and school administrators, and in 2016 the Tenth District Court upheld their rulings.

Several large urban districts, like Chicago Public Schools, have launched efforts to reform the way they discipline students, with an eye toward reducing racial disparities. Of the 380,000-plus students enrolled, nearly 40 percent are black, while under 10 percent are white.

About four years ago, district officials began implementing "restorative justice" strategies that sought to address the underlying causes of misbehavior. An alternative to punitive discipline methods, restorative justice strategies include "peace circles" that bring together students involved in disagreements. The district also retrained police officers. Since then, it has reduced its suspensions and expulsion rates, as well as referrals to police in all racial groups — and has been slowly removing full-time police officers from schools.

"We’re very, very specific that we don’t ask the police officers to intervene when there’s merely a disciplinary issue that can be handled by the school administration," said Jadine Chou, head of security for Chicago Public Schools.

But racial disparities still exist. According to federal data, in 2013-2014 black students in Chicago were five times more likely to be referred to law enforcement than their white peers.

'The Bad Guy Wears the Handcuffs'

Joshua Caruso, Ethan’s father, said the incident left the boy who loves his scooter and Batman withdrawn and frightened of police officers. "He’s O.K. at home where he’s safe, but if you take him out of his environment he panics," Caruso said, adding that he and his wife are planning a trip to a police station so Ethan can meet police officers.

"Be very diligent," Caruso said he would tell other parents of children with disabilities. "Listen to your kids. When they tell you something, listen to it and ask questions."

Just like Kalyb Wiley-Primm, Ethan said he was "mad" and "scared" because "I didn’t want to go to jail."

“Our position is that there’s no situation in an elementary school where a student of that age should ever be handcuffed,” says Gillian Wilcox, an attorney with the ACLU of Missouri who is representing Kalyb. He and his mother are suing the Kansas City school district in federal court for violations of Kalyb’s constitutional rights by unlawfully restraining him and using excessive force. The family wants to see changes in policy and in the training of security officers, according to Wilcox.

Kansas City Public Schools denies that Kalyb was unlawfully handcuffed and restrained and denies that his constitutional rights were violated or that he is entitled to relief. A spokesperson at the time of the incident said that handcuffing students was one of “a number of methods our staff can use,” according to the ACLU lawsuit.

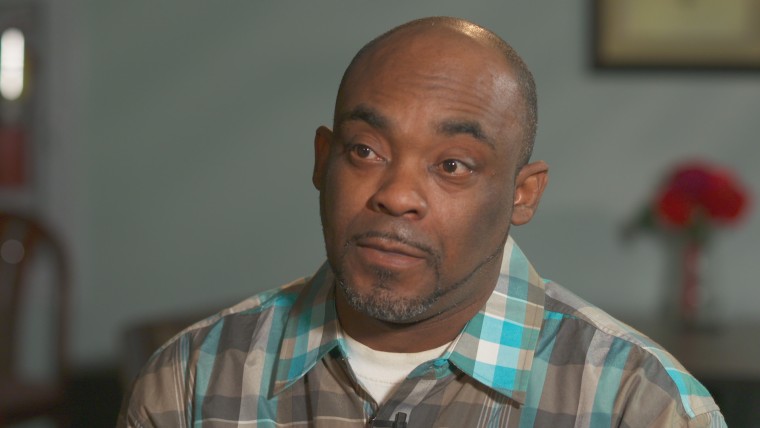

Like Ethan’s dad, Kalyb’s father, Derrick Wiley, said he worries that his son now will have a tainted view of law enforcement — and of himself.

"When kids play, what do they associate handcuffs with?" Wiley said. "The bad guy. The bad guy wears the handcuffs. The good guy puts the handcuffs on the bad guy."