CHICAGO — At the center of Louis Beaudion’s dining table sits a simple ceramic urn, draped in sky-blue rosaries, that arrived last month from the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office.

The ashes inside are all that remain of his 22-year-old son, Edward, who vanished in the summer of 1978, a mystery that wore his heart, tested his faith, and tossed his family into the slipshod system of tracking America’s lost.

Slowed by bureaucratic neglect and investigative missteps, the search spanned 36 years. The anguish lingered like a tumor.

“It never goes away,” Beaudion, 86, said between sobs as he stared at the floor of his home in northwest Chicago. The retired bookbinder’s arthritic hands trembled in his lap. “You wake up in the night, thinking about it. Always wondering why.”

There are thousands of families like Beaudion’s who are searching for loved ones, and thousands of people like Edward who died without being identified, their bodies sitting in morgues and graves around the country. There are ways to connect the searchers and the vanished, but the solutions to what the National Institute of Justice calls a “silent mass disaster” remain woefully underused.

The Beaudions learned that the hard way. It took a dogged detective and long-dead serial killer John Wayne Gacy to show them.

Edward Beaudion was, his father says, a model son. A devout Catholic, Edward sang in the choir and taught catechism. He graduated from Loyola University in spring 1978 and planned to start teaching third grade in the fall. He still lived at home, and always called when he was running late.

That is why, when he didn’t immediately return from a friend’s July 22, 1978 wedding in a nearby suburb, his family knew something was wrong.

The police weren’t convinced. When Louis Beaudion and his daughter, Ruth Beaudion-Rodriguez, showed up at the local precinct house, they told him to sit tight for a few days.

“Aw, he’s probably in a hotel room,” Beaudion recalled an officer saying.

That was generally the way police treated missing persons cases back then: as low priorities. A missing person’s case wasn’t necessarily a crime, and could be exhausting to close. It often fell to family to raise a fuss.

The Beaudions did just that. They insisted on filing a police report. They blanketed their neighborhood with handmade posters. The disappearance made local news.

Then, in August, police in Missouri recovered Beaudion-Rodriguez’s green Chevy Nova, which Edward had borrowed to get to the wedding. It was being driven by Jerry Jackson, a 26-year-old petty criminal from Chicago’s South Side. Edward’s wallet, credit cards and coat were inside.

In a recorded statement, Jackson told Chicago police he’d knocked Edward unconscious in a confrontation on a city street early in the morning of July 23. Jackson put him in the car and drove south of the city, dumping him off a side road. He kept the car and used Edward’s credit cards for gas.

Police spent the next few weeks searching for Edward’s body. Without it, authorities said they couldn’t prosecute Jackson for murder. He was convicted of auto theft, sent to prison and released less than two years later.

As Edward’s case languished, his bedroom and the rest of the Beaudion home remained untouched. “My mom thought if he came home she wanted everything to be the same,” Beaudion-Rodriguez said.

In December 1978, more than a year after Edward’s disappearance, an unrelated missing persons case led police to the home of John Wayne Gacy, a construction contractor and amateur clown who lived just outside the city. A search uncovered the remains of 29 boys and young men buried under the house, garage and driveway. He confessed to throwing another four into the Des Plaines River. Some had been dead for years.

The horrifying discovery, and the painstaking attempts to identify Gacy’s victims, exposed systemic failings in the way missing persons cases were investigated. Families of lost children came forward by the dozens, wondering if Gacy had taken their kids. Among that desperate lot were the Beaudions, who by then wondered if Jackson had lied.

This was before DNA was developed as a crime-solving tool, so the Beaudions submitted x-rays of Edward’s right knee, which had a surgical screw in it. Investigators examined the evidence and reported that there was no match with the Gacy victims.

Eventually, police identified all but eight of the victims. Before arranging for those remains to be buried in local cemeteries, the medical examiners set aside the jaws and teeth in case more families came forward.

The last the Beaudions heard from detectives was the mid-1980s, when one showed up at Beaudion-Rodriguez’s door, handed her a file and left. Inside were all the reports on Edward’s disappearance, including Jackson’s confession. It was difficult to interpret the move as anything but a final act by an officer who sensed the case was dead.

The file was still collecting dust in April 2008, when three teenaged siblings hiking in the woods about 30 miles southwest of Chicago came upon a sock with bones in it. When police arrived, they found other pieces of a human skeleton, some of it in tattered clothing. They were taken to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office, where a doctor found a surgical screw in the right knee. He listed the cause of death as “undetermined.”

The bones were then placed into storage. It would be years before someone bothered to look for them.

“We didn’t have anything to lose.”

Death investigators don’t tend to think of their work as part of a larger story. But every so often, one cracks the lid on a profound and systemic injustice.

That happened to Cook County Sheriff’s Office Detective Jason Moran in 2009, when he was assigned to investigate a cemetery that was dumping remains into mass graves. That scandal led Moran to a similar situation at a cemetery that had a contract with the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office to bury unidentified bodies. Instead of keeping track of them, or saving samples for later identification, the cemetery picked up the remains in a rental truck, then dumped them into an unmarked mound.

The discovery turned Moran’s attention to the medical examiner’s office, where he found dozens more sets of unidentified remains in storage.

Moran, 37, soon became a voracious student of DNA, missing persons networks and forensic anthropology.

This was a field you could devote a career to: tens of thousands of people who vanish every year, an estimated 40,000 sets of human remains that have not been identified, a fraction of which have been entered into federal crime-information databases. There was a growing movement to change things, led by the National Institute of Justice, which pushed for reform legislation, funded DNA labs and spearheaded the creation of the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs, an online database in which law enforcement and the general public enter and search information on missing persons and unidentified dead.

Moran was just beginning to understand the power of these networks. He looked at the hill of buried remains and wondered how many solvable cases lay under the surface.

He asked the chief medical examiner if she arranged for DNA to be taken from the bodies, or kept track of where they were buried. The answer was no.

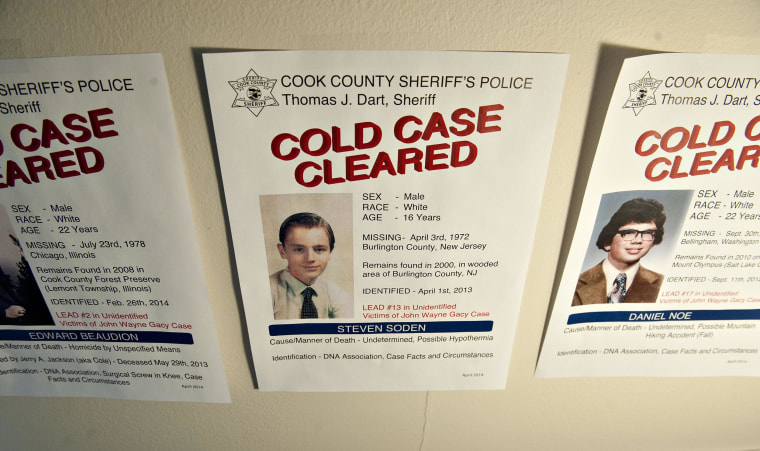

The detective told his boss, Cook County Sheriff Thomas Dart, who asked him to scan cold case files to determine how many were unidentified bodies. Moran found dozens. But eight leapt out at him: the unnamed Gacy victims.

Dart told Moran to re-examine the Gacy cases. The victims and families deserved it. The publicity could also help raise awareness about the unfolding crisis.

Moran went back to the medical examiner’s office for the jaw and teeth samples that had been saved before the victims were buried and was told they had been dumped in the unmarked hill a year earlier. Moran had a crew tear into the hill, where they found the bones in a box. He took them to the University of North Texas’ Center for Human Identification, one of the country’s premier forensic DNA labs.

The lab was able to obtain workable DNA profiles of four of the eight unknown victims. So Moran ordered exhumations of the rest, and delivered more samples to the lab, which completed the remaining profiles.

In October 2011, Dart held a press conference announcing his office was reinvestigating the Gacy unknowns. He asked families who thought their missing loved one could have been murdered by Gacy to provide DNA samples that could be compared with the victims’.

The notice spread across the country. The phones rang off the hook. Despite having been told decades earlier that her brother’s body was not among the victims, Beaudion-Rodriguez submitted an online request. “We didn’t have anything to lose,” she said.

“I would have been pounding my fist on the table going, ‘Whose head is going to roll for this?’”

When Moran saw Beaudion-Rodriguez’s email, he called right away, and the next day showed up at the Beaudions’ house.

They told Moran their story. Beaudion-Rodriguez, 63, a retired office worker with short graying hair and a warm smile, did most of the talking. Her father, remarkably fit with a silvery Fu Manchu moustache, was more pensive. His wife had died, heartbroken, in 2001, and he remained emotionally fragile.

The detective swabbed the insides of their cheeks and sent the samples to the Center for Human Identification to build a DNA profile. The results came back weeks later: the lab had found no association with the remaining Gacy victims. The trail again went cold. But Moran reminded them that their family profile would remain in a federal database.

The detective moved on. He’d received about 125 leads so far. He was clearly scratching the surface of a national epidemic.

Almost immediately, there was a hit, from a family that lived not far from the Beaudions. Their missing boy was William Bundy, and through siblings’ DNA and other biological data, Moran determined that he was one of the eight unnamed Gacy victims.

Over the next couple years, Moran made other connections, none linked to Gacy: some who’d died under unexplained circumstances, some who’d died of natural causes, some who’d run away and were still alive.

Dart and Moran realized that if all law enforcement agencies made similar efforts – collect DNA from all unidentified bodies and take DNA from the families of missing people – there was no telling how many cases could be solved. This discovery thrust them into a growing movement that seeks to set national standards and combine federal databases with the public NamUs database.

“When it came to dealing with missing persons, as a society we really didn’t spend a lot of time focusing on it,” Dart said. “And that hasn’t really changed that much. Some law enforcement agencies are much more engaged, some are much more high tech, and others still treat it the same way. They fill out a piece of paper, it goes in a file somewhere and then, well, we’ll hear from you later, maybe.”

Dart and Moran began to reform the way Cook County handled its missing persons and unidentified deceased. One new rule outlined the collection of DNA from missing persons’ biological siblings and parents. Another required that every set of unidentified remains be submitted for DNA samples and their profiles uploaded into the national databases. That process began in 2012 and would take years to complete.

In February 2014, Moran called the Beaudions and asked to stop by. “He said, ‘We found a match. We found Edward’s remains.’” Beaudion-Rodriguez said. “And, naturally, my dad and I broke down in tears.”

Among the remains in storage at the medical examiner’s office were the bones found by the teenaged hikers in April 2008. The DNA had shown an association with the Beaudions’. Jackson’s confession had been true.

Moran asked the Beaudions not to share the news with anyone. He planned to track down Jackson and charge him with murder.

But Moran’s search revealed that Jackson had died less than a year earlier.

Moran was furious. If not for the backlog at the medical examiner’s office, he would have had a shot at finally obtaining justice for the Beaudions. “I would have been pounding my fist on the table going, ‘Whose head is going to roll for this?’” Moran said. “But not Mr. Beaudion and Ruth. They said, ‘I’m just thankful that we found out what happened.’”

The detective and the sheriff decided that would be the Beaudions’ last indignity. They pressed the medical examiner’s office,which did not face a criminal probe but was now run by a new chief, to cover the costs of handling Edward’s remains. Louis Beaudion asked that they be cremated and returned to him so when he died, he could be buried alongside his son and his wife.

“Can you imagine not knowing where your child is?”

When the weather warmed, Moran and Dart drove the Beaudions to the Black Patridge Woods Forest Preserve in Lemont, Illinois. They descended a thick ravine until they came upon a clearing where authorities had been digging for more of Edward’s remains. Louis pulled out a white cross, dropped to his knees and began hammering it into the dirt. He and his daughter began to weep. When he finished, they prayed.

“I felt more pain because it bothered me as to how my brother was left there,” Beaudion-Rodriguez said. “But yet I know my brother is resting in peace.”

Moran has closed 11 cases since October 2011. He’s analyzed dozens of leads, with new ones still coming in.

“These are some of the saddest people you’d ever want to meet,” Moran, who has young kids himself, said. “Can you imagine not knowing where your child is?”

In late April, Dart publicly announced the results of the Beaudion case. The Beaudions were inundated with calls and visits from relatives and old friends. The family plans to hold a memorial service on Friday at the Immaculate Heart of Mary Church, where Edward sang in the choir.

On June 5, Moran showed up at the Beaudion home with a final delivery: an urn containing Edward’s ashes. The detective set it on the dining table. Beaudion watched silently, then said: “You brought my boy home.”

The Cook County Sheriff Department’s Gacy hotline remains open to families who wish to submit their DNA. More information is at the department’s website, or at (708) 865-6244.