Editor's Note: This is the first part in a three-part series from our partners at Reuters.

LEHIGHTON, Pennsylvania — Brayden Cummings turned 6 weeks old the morning his mother suffocated him.

High on methamphetamine, Xanax and the methadone prescribed to help her kick a heroin habit, 20-year-old Tory Schlier told police that she was “fuzzy” about what happened to her baby boy.

Police weren’t. In an affidavit, the officer who went to Schlier’s house on October 17, 2014, said the mother had fallen asleep on Brayden, “causing him to asphyxiate.”

Like more than 130,000 other children born in the United States in the last decade, Brayden entered the world hooked on drugs — a dependency inherited from a mother battling addiction.

Click Here to Read the Reuters Series on Drugs and Newborns

A 12-year-old federal law calls on states to take steps to safeguard babies like Brayden after they leave the hospital. That effort is failing across the nation, a Reuters investigation has found, endangering a generation of children born into America’s growing addiction to heroin and opioids.

In his first three weeks of life, Brayden suffered through a form of newborn drug dependency called Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. He trembled and wailed inconsolably, clenching his muscles and sometimes gasping for breath as he went through withdrawal.

When Brayden improved, Lehigh Valley Hospital released him to Schlier and the boy’s father, a 48-year-old with a criminal record. But doctors neglected to take a critical step: They failed to alert child protection workers to the baby or his drug-addicted mother. Three weeks later, Brayden was dead.

“I’d say he didn’t have a chance in life,” said David Cummings, Brayden’s grandfather. “He was doomed, that kid, he really was.”

Reuters identified 110 cases since 2010 that are similar to Brayden’s: babies and toddlers whose mothers used opioids during pregnancy and who later died preventable deaths.

Being born drug-dependent didn’t kill these children. Each recovered enough to be discharged from the hospital. What sealed their fates was being sent home to families ill-equipped to care for them.

Like Brayden, more than 40 of the children suffocated. Thirteen died after swallowing toxic doses of methadone, heroin, oxycodone or other opioids. In one case, a baby in Oklahoma died after her mother, high on methamphetamine and opioids, put the 10-day-old girl in a washing machine with a load of dirty laundry.

The cases illustrate fatal flaws in the attempts to address what President Barack Obama has called America’s “epidemic” of opioid addiction, a crisis fed by the ready availability of prescription painkillers and cheap heroin.

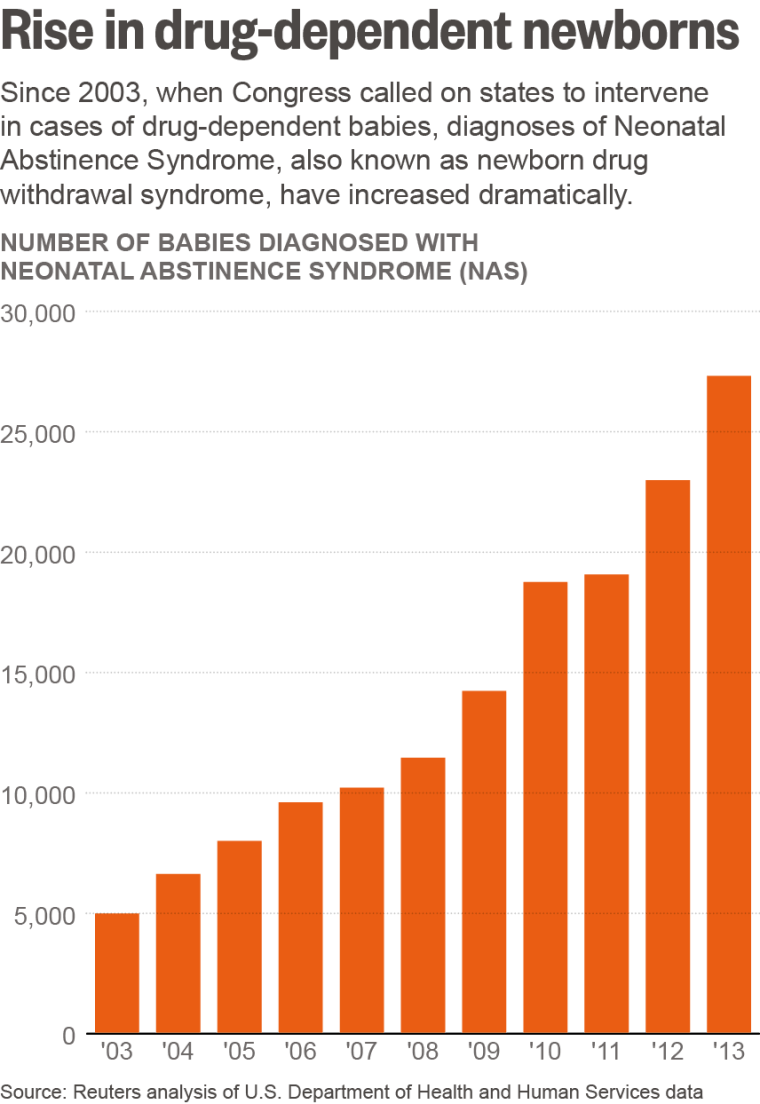

In 2003, when Congress passed the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act, about 5,000 drug-dependent babies were born in the United States. That number has grown dramatically in the years since. Using hospital discharge records, Reuters tallied more than 27,000 diagnosed cases of drug-dependent newborns in 2013, the latest year for which data are available. On average, one baby was born dependent on opioids every 19 minutes.

The federal law calls on states to protect each of these babies, regardless of whether the drugs their mothers took were illicit or prescribed. Health care providers aren’t simply expected to treat the infants in the hospital. They are supposed to alert child protection authorities so that social workers can ensure the newborn’s safety after the hospital sends the child home.

But most states are ignoring the federal provisions, leaving thousands of newborns at risk every year. Reuters found that at least 36 states have laws or policies that don’t require doctors to report each case. No more than nine states and the District of Columbia appear to conform with the federal law. And statutes or policies in the other five states are murky and confusing, even for doctors and child protection workers.

“Those kids could and should be alive today and thriving”

In three-quarters of the 110 fatalities that Reuters identified, the mother was implicated in her child’s death; in others, her boyfriend, husband or another relative was.

In 75 of the cases, child protection workers were notified but didn’t take protective measures specified in the federal law.

In Brayden’s case and a dozen more, hospitals didn’t report a drug-dependent baby’s condition to social services and the child died after being sent home.

“Those kids could and should be alive today and thriving,” said former U.S. Representative Jim Greenwood, a Republican from Pennsylvania who authored the provisions in the 2003 federal law. “I would’ve hoped that the whole system — starting at the federal and state levels, the obstetricians and pediatricians – would’ve gotten it straight by now. That they haven’t is a national disgrace.”

One reason babies go unprotected: Many states don’t require hospitals to report drug-dependent newborns if the mother was taking methadone, painkillers or other narcotics prescribed by a doctor.

That exemption stems from a well-meaning effort to avoid stigmatizing mothers who are being treated for addiction or other medical problems. Taking methadone under a doctor’s care is generally safer for a baby and its mother than if a mother tries to stop taking opioids altogether, neonatologists said.

But those good intentions ignore a difficult truth: A mother who abuses methadone or other legal opioids can be just as dangerous to her newborn as a parent high on heroin. In at least 39 of the cases in which children died, Reuters found, the mother was taking methadone or another drug that had been prescribed.

In each of the 27,000 cases of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome diagnosed in 2013, hospital workers were aware of the baby’s condition. Patient discharge records show they treated the child for the syndrome.

Doctors who specialize in these cases say the condition, while sometimes agonizing for the newborn, is treatable and needn’t result in long-term harm to the child. But a diagnosis made in the first days of the baby’s life should serve as a warning, they say. It often indicates that a mother is struggling with addiction, raising questions about a family’s ability to care for the infant.

“This is precisely the time when a woman is ripe for relapse,” said Lauren Jansson, director of pediatrics at the Center for Addiction and Pregnancy at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “She’s feeling terrible, tired, depressed, anxious and guilty.”

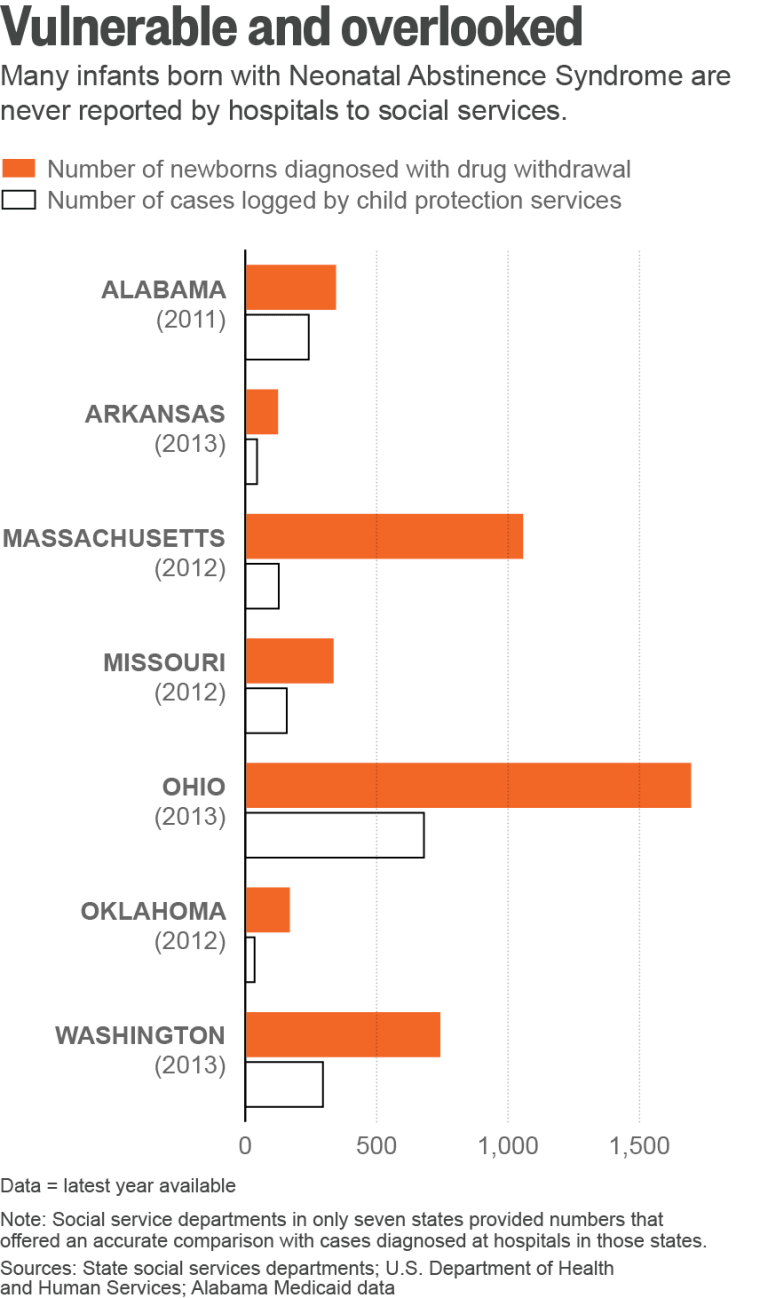

Data kept by state governments suggest that thousands of these babies and their mothers are never referred to child protection services.

Reuters made that determination by comparing the number of newborns diagnosed by hospitals as drug-dependent with the number of cases referred to state child welfare authorities. Only seven states specifically tracked referrals of newborns in drug withdrawal. In those states, the total number of cases logged by child protection services was less than half the number of children diagnosed.

“These are just deaths waiting to happen,” said Greenwood, who spent three years as a child protection worker before serving six terms in Congress.

Because so many drug-dependent newborns go unreported, no one knows exactly how many children are injured or killed while in the care of parents struggling with addiction.

Reuters filed more than 200 Freedom of Information Act requests with federal, state, county and city agencies, and reviewed about 5,800 child fatality reports from across the United States to identify such cases. Reporters also scrutinized tens of thousands of pages of reports by police, hospitals, medics, coroners and lawyers.

By examining fatality reports and other public records, the news agency was able to identify 110 examples of children who died across 23 states.

The toll is almost certainly higher. Most states made available only partial information on the circumstances of infant deaths. Some of the largest states, including New York, declined to disclose any reports about child fatalities.

Even so, researchers said the Reuters investigation represents the most comprehensive examination of the perils facing drug-dependent newborns after they are sent home.

“If we start looking at it like you’re doing, we’re going to find more of these babies,” said Theresa Covington, director of the National Fetal, Infant and Child Death Review Center, a government-funded non-profit group. She called the Reuters findings “groundbreaking and heartbreaking.”

“That Baby Is In Serious Danger"

During the so-called crack-baby epidemic of the 1980s, public concern focused on whether children exposed to cocaine in utero would face long-term developmental problems. Less examined was whether babies born with narcotics in their bodies were in danger after they were treated and released from the hospital.

A longstanding law, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, was amended in 2003 to address that issue. The amendment orders states to set up systems to ensure that each case in which a baby is born drug-dependent is reported to child protection authorities. Social services are then to develop a “plan of safe care” for the child.

The law also makes clear that those referrals are not evidence of abuse.

The House majority leader then — Tom DeLay, a Republican from Texas — spoke in Congress about the importance of the amendment. “When child protection workers aren’t told that a baby was born addicted to drugs,” he said, “that baby is in serious danger.” The new legislation “sends a clear message to the states: Drug-addicted newborns must be protected.”

Although the amendment passed with almost no opposition, its impact has been limited. At the time, the National Conference of State Legislatures said that many states would need to pass new laws to meet the federal provisions. Few have.

Congress offers federal funding for states that comply with the law. But the amount of money tied to the provisions is tiny. This year, it ranged from $83,673 for the District of Columbia, which does comply, to $2.8 million for California, which doesn’t.

Despite the widespread lack of compliance, Reuters found that no state has ever lost federal funding for failing to meet the law’s provisions.

Today, most states require health officials to report only babies who were exposed to illicit narcotics. That means child protection services may never learn of babies suffering withdrawal from opioids that were legally prescribed to pregnant mothers. Some state policies are so muddled that even child welfare officials are confused about the reporting requirements.

“A lot of officials [say], ‘We don’t report when the mother is trying to get better’”

Laura Velez, deputy commissioner of New York state’s Office of Children and Family Services, initially told Reuters that doctors there must report all cases of drug-dependent newborns, regardless of whether the mother was taking “legal or illegal drugs.” But after checking with a lawyer in her office, Velez offered a different interpretation: Doctors aren’t obligated to report cases in which the mother is using prescribed drugs and “following the course of treatment appropriately.”

At the other extreme, states such as Alabama and Tennessee have taken a punitive approach to expectant mothers battling addiction, enacting laws that make opioid abuse during pregnancy a crime in certain circumstances. Those provisions run counter to the spirit of the federal law, which explicitly states that identifying a drug-dependent newborn shouldn’t be construed as requiring prosecution. Some well-intentioned doctors say the punitive measures give hospitals a strong incentive to keep quiet about certain kinds of cases.

“A lot of officials — nurses, social workers — say, ‘We don’t report when the mother is trying to get better,’” said Ila Baugham, a retired pediatrician in North Carolina who reviews cases of unexpected child fatalities. “I always come back and say, ‘Well, it’s not about the mother. What about the baby?’”

The White House has done little to address the problem, some doctors say. In an October speech, President Obama said he “started studying this issue — what’s called opioids,” when he entered office in 2009. “And I was stunned by the statistics.”

His administration convened a conference on opioid-dependent babies in 2012; three years later, White House “action items” included updating agency websites. Last month, Congress passed a bill directing the administration to move faster and devise a national strategy within a year. A White House spokesman said the new law “builds on ongoing efforts.”

Loretta Finnegan, the doctor who developed a widely used medical scale to assess Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, said she is “discouraged and frustrated” by the administration’s response. Statistics showing the spike in cases have been available since at least 2012, she said.

“It’s 2015. When are they going to start doing something?” Finnegan asked. “We know these babies are very difficult to care for. If you do not create the proper conditions for mother and child, when they go home it’s a setup for the mothers or others in the home to commit abuse.”

Infants with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome are sometimes born into excruciating misery. As they go through withdrawal, some shake, struggle to eat and often sputter and choke during feedings. They suffer fits of sneezing and severe diarrhea. Many begin crying at the smallest stimulus, including a mother’s smile. They can cry with such force that their bodies shudder.

“It’s a panicked, high-pitched wail, almost desperate, a sound you don’t forget,” said Kimberly Nelson, nurse manager of the neonatal intensive care unit at the Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

The symptoms are often worst during the first five weeks of life but can last three to six months, challenging even the most patient parents. The newborns rarely achieve deep sleep. As they endure withdrawal, they crave the darkness and calm of the womb, conditions almost impossible to replicate at home. In West Virginia, cases have become so frequent that one hospital created a unit where babies are weaned off the drugs in dimly lit rooms, sheltered from bright light and commotion.

“It’s relentless. There’s no break,” said Rhonda Edmunds, a neonatal nurse in Huntington, West Virginia. “You can just imagine a sleep-deprived parent, who can’t cope with her own issues, let alone their baby, and how that can lead to abuse or neglect.”

“You're On That Baby"

In the 110 deaths Reuters identified, expectant mothers typically had been using heroin, synthetic painkillers that include such drugs as Percocet and OxyContin, or methadone, an opioid often prescribed as an alternative to heroin or the other medications.

Like Brayden Cummings, the Pennsylvania baby who died at 6 weeks of age, many of the children suffocated after hospitals released them to mothers unable to care for a baby.

In December 2012, a Kentucky hospital sent a newborn and a prescription for Percocet home with a 28-year-old mother who was being treated for opioid addiction. Child protection authorities weren’t notified about Angelica Richardson McKenney’s newborn, Lynndaya. Under Kentucky law, the case didn’t have to be reported because McKenney’s opioid-replacement drug, Subutex, had been prescribed.

Five days later, on Dec. 10, Lynndaya was dead. A 36-page state report details the final hours of the newborn’s life.

The night before Lynndaya died, McKenney later told police, she took three different medications: the opioid Percocet, the anti-anxiety medication Xanax, and Subutex. Lynndaya’s grandmother noticed that McKenney’s “knees were buckling under her when she stood.” McKenney recalled that she later fed the infant but “didn’t know what she did with Lynndaya after that.”

The next morning, Lynndaya’s grandmother tried to wake McKenney, who lay at the foot of the bed. Twice, the grandmother asked where the baby was. Then she saw a corner of Lynndaya’s blanket beneath McKenney. “Oh my God,” the grandmother told a still-high McKenney, “you’re on that baby.”

According to the death report, the state of Kentucky ruled that McKenney’s “neglect” had caused her baby’s death. Local prosecutor Douglas Miller said there wasn’t enough evidence of “reckless” or “wanton” conduct, as required by state law, to charge her.

Harrison Memorial Hospital and the doctor who delivered Lynndaya knew of McKenney’s drug problems. The state report said that Lynndaya “tested positive for narcotics” when she was born. McKenney “has been testing positive throughout her pregnancy for opiates, benzodiazepines, and marijuana, none of which she had a prescription for,” the report said.

But no report about McKenney’s drug use was made to child protection authorities when Lynndaya was born, state records show. Hospital spokeswoman Mollie Smith declined to talk about the case, citing medical privacy.

Derek Clarke, the doctor listed on the hospital discharge document, delivered Lynndaya by Cesarean section. He later sent McKenney home with the prescription for Percocet, one of the drugs she took the night before she smothered her baby. The discharge also notes that McKenney “has been taking Subutex throughout her whole pregnancy.”

Contacted by Reuters, Clarke defended his decision to send McKenney home with Percocet. “Just because they’re a drug addict doesn’t mean we’re not going to give them something for their pain,” he said.

The day before Lynndaya died, pharmacy records show, Clarke also prescribed Xanax, which McKenney took with the Percocet and Subutex. Studies have shown that combining Subutex and Xanax can be particularly dangerous. Clarke did not respond to questions about the Xanax prescription.

McKenney said Clarke should have known better than to give her the prescriptions. “I’m an addict. It was my fault, of course, and also it was his fault for offering me the medicine.”

McKenney said she has been off drugs for about two years now. She said she wishes social services had been more involved when Lynndaya was born.

“I think if I had been under the microscope, so to speak, I think things would have been a lot different with somebody coming in and looking at me,” she said. “That probably would’ve changed everything.”

A Fatal Mixture

Other children died of drug poisoning — not from the narcotics in their bodies at birth but from doses administered after they left the hospital.

In Utah, a 17-month-old girl named Jaslynn Raquel Mansfield died last year of acute methadone toxicity. Her mother, Courtney Nicole Howell, was on prescription methadone during and after her pregnancy.

Howell told authorities that she twice used a syringe to mix the narcotic with Children’s Tylenol. Her reasoning: Jaslynn “wouldn’t eat or sleep and she wasn’t her normal baby any more,” according to a 42-page police report marked “confidential.” “Courtney admitted that she didn’t know what to do to get Jaslynn help,” the report said.

In August, Howell was sentenced to up to 30 years in prison after pleading guilty to manslaughter and exposing a child to drugs.

“The way she chose to care for the child was reckless,” Judge David Hamilton said at sentencing. “She brought the child into the world saddled with her addictions and her actions, and then she compounded that.”

In a phone interview from the Timpanogos Women’s Correctional Facility near Salt Lake City, Howell said her newborn went through drug withdrawal at the hospital for 16 days. But the Salt Lake Regional Medical Center never reported the case to child protection services.

Utah is among the states that don’t require reporting cases of newborns exposed to drugs prescribed to their mothers. Louise Swensen, director of risk management for the hospital, said a baby in withdrawal wouldn’t be reported to child protection unless the mother was abusing drugs or doctors had other safety concerns.

Charri Brummer, deputy director of the state Division of Child and Family Services, said the state “would prefer” to be notified of all drug-exposed babies. In this case, she said, the state received no drug-related reports on Howell before Jaslynn’s death.

In many ways, Howell represented the kind of vulnerable parent the federal law was meant to help. Not only was her newborn going through withdrawal, but Howell also was homeless. Jaslynn’s father had died three months earlier from a heroin overdose. “I feel I was lucky my daughter had to stay (in the hospital) that long because I had no place to take her,” she said.

After she and Jaslynn were released, Howell said, they went to live with her late boyfriend’s father and then to a women’s shelter. She said the hospital gave her about four micro-doses of morphine to finish weaning Jaslynn off opioids. Howell herself continued to use methadone and other drugs, she said.

Today, she said, she wishes she had been reported to child protection services when Jaslynn was born. “I would have welcomed the help,” Howell said, “and it would have changed my life.”

Unmonitored

In the case of Brayden Cummings, the 6-week-old who was accidentally suffocated by his mother in Pennsylvania, child welfare authorities learned of the boy only after it was too late.

In September, Brayden’s mother, Tory Schlier, pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter and was sentenced to at least 15 months in prison. At sentencing, she told a judge that she had been happy when she got pregnant but “very scared to bring a helpless human being into the world knowing that child would be my responsibility.”

Schlier’s drug problems were no secret. When Tory was a teenager, her parents had sought the county’s help for her “incorrigible behavior and drug use,” a state report said. On probation for theft and pregnant with Brayden, Schlier was jailed in May 2014 after testing positive for heroin, documents show. A judge released her on July 31 — about a month before Brayden was born — on the condition that she take methadone, the opioid-replacement drug.

The lawyer representing Schlier in Brayden’s death said that the baby’s life could have been saved had the hospital alerted social services. But when Schlier and Brayden were sent home, attorney Jennifer Rapa said, “no watch was in effect and no services were offered.”

Not even the county officials who reviewed Brayden’s death can explain why.

The review team was led by child protection workers at Carbon County Children and Youth Services, the local welfare agency. In a report early this year that has not previously been made public, the team wondered how Schlier “could have been seen by so many different professionals before and after the baby’s birth and yet no one considered calling Children and Youth to file a report.”

Even though Schlier was on methadone during her pregnancy, social services were not alerted, the review team wrote. Then, after Brayden was born drug-dependent, he “was prescribed methadone following birth yet no one had called Children and Youth.”

Brayden was seen “by his pediatrician, who was also aware of the baby being on methadone, but yet no one had called Children and Youth,” the review team wrote.

The pediatrician, Narayana Gajula, said he was surprised to learn from Reuters that the hospital never reported the case. At the time, Pennsylvania required doctors, including Gajula, to report all cases in which a child was born drug-dependent, as the federal law spells out.

“There’s no doubt this baby was at risk, and the mother had already been on drugs,” Gajula said.

He said that his office generally calls child protective services when babies seem at risk of neglect or abuse.

He assumed hospital administrators automatically reported the case to social workers, he said. “I don’t know what transpired at the hospital.”

Citing patient privacy, Brian Downs, a spokesman for the Lehigh Valley Health Network, said neither the hospital nor its staff doctors will comment on the case or the county’s report.

Gajula said he saw Brayden twice in the week before the baby’s death, and “it seemed to be going fine.”

It wasn’t, Schlier wrote in a letter to Reuters from prison. She said she wished that the hospital “had someone check in at our home daily to see how things were going,” for her and for Brayden. “I was an addict, and it was well known to everyone, but no one seemed to care!”

It isn’t clear who finally did alert child welfare officials to Brayden. The state’s report redacted that information. But the report does note that the phone call didn’t come until early this year – 80 days after the baby had died.

In June, state lawmakers voted to change the policy for reporting babies born dependent on drugs: They loosened it. Today, if a drug-dependent baby is born to a mother using prescribed drugs — such as the methadone Schlier had been taking — doctors no longer need to alert social services.

Pennsylvania’s safety net for the babies of the opioid epidemic is now weaker than it was when Brayden Cummings died.

Additional reporting by Blake Morrison and Mimi Dwyer

About the Series

Reporter Duff Wilson reviewed more than 50,000 pages of documents and interviewed more than 300 people to assess the impact of opioids on newborns. The documents included about 5,000 child fatality reports and tens of thousands of additional pages of medical records and other documents obtained through about 200 public records requests. To get those documents, Reuters began filing Freedom of Information Act requests in 2014 with federal, state, county and city agencies.

Reporters interviewed mothers in seven states — including three mothers who are currently in prison — as well as doctors, nurses, social workers, drug counselors, prosecutors, defense lawyers, academics, child protection workers, lawmakers and relatives of people struggling with addiction.

To track the dramatic increase in babies born drug-dependent, Reuters analyzed hospital patient discharge data kept by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The news agency surveyed each state and the District of Columbia to assess policies and performance on two key parts of federal law – mandatory reporting of drug-withdrawing newborns and the disclosure of child fatality review reports.

To determine whether a child’s death may have been related to the mother’s drug use, Reuters looked at cases since 2010 in which a newborn was diagnosed as dependent on drugs or the mother was found to be using opioids during pregnancy. Then reporters examined whether the deaths of those children, each of whom had been released from the hospital, could have been prevented.

The 110 cases that Reuters found fit the definition of “preventable death” used by most states. It is contained in a glossary of terms to help officials identify and report such cases to the National Center for the Review and Prevention of Child Deaths, a government-funded non-profit group. According to the definition, “A child’s death is considered to be preventable if an individual or the community could reasonably have done something that would have changed the circumstances that led to the child’s death.”

The 110 examples likely represent the “tip of the iceberg,” said Theresa Covington, a presidential appointee and director of the national center.

Covington said the news agency’s findings were groundbreaking, in part because tracing the circumstances of a child’s death back to the conditions at birth is often difficult.