Even as critics express concern about the gender pay gap under President Donald Trump's administration, there may still be reason for hope.

While federal policy-making aimed at tackling the wage gap could stall under Trump's administration, equal pay advocates are optimistic that state legislatures will take the lead on protecting women in the workplace.

Since 2016, state lawmakers have introduced at least 180 bills across the country aimed at shrinking the pay gap. Seven were enacted, dozens are pending and nearly 50 either failed or were vetoed. A year prior, 76 equal pay-related bills were introduced in 33 states.

And it’s not just progressive states like California taking the wage gap seriously. Louisiana, North Dakota and Utah are just three examples of Republican states advancing such legislation, said Emily Martin, a legal expert on equal pay.

In North Dakota, for instance, a bill passed in 2015 strengthening employer's salary reporting requirements. The state, which overwhelmingly voted for Trump in the 2016 election, proves the issue of pay equity is still being addressed in conservative areas.

“I’m glad that states are really focusing on equal pay and exploring new policy solutions to ensure women are paid equally to men, in part because federal policy-making is at best stalled on this issue, and at worst, we might be seeing rollbacks in coming years,” Martin, who serves as general counsel and vice president for workplace justice at the National Women’s Law Center, told NBC News.

While equal pay laws passed by Congress include the Equal Pay Act passed of 1963, states are offering creative solutions to expand protections for women and close federal loopholes.

Don't Ask, Don't Tell

Bills that prohibit employers from requiring job applicants to reveal their salary history can prevent pay discrimination from following a woman throughout her career.

In 2016, Massachusetts enacted first-of-its-kind legislation forbidding employers from inquiring about salary history. Since then, California has followed suit and nearly 20 states have introduced similar measures.

“If your new employer is setting how much you make based on how much you made at your last job, given that women tend to be paid less than men, it has the effect of replicating those wage disparities through a woman’s career as she shifts from job to job,” Martin said. “We’ve seen a lot of interest in other states in replicating [Massachusetts’s law].”

Opening Up Conversations on Pay

California, Delaware, Maryland and Connecticut are among the states in 2016 that strengthened laws prohibiting bosses from retaliating against employees who discuss their wages with coworkers. As of 2017, 17 states had "pay secrecy" laws on the books, and some are looking to strengthen existing law. But several states, including Arizona, continue to allow such practices from employers.

“You can’t challenge pay discrimination if you don’t know you’re being paid less than a male coworker, but a lot of employers either have formal policies prohibiting employees from talking to each other about wages or strong implicit disapproval for employees talking to each other about wages,” Martin said.

Delaware Gov. Jack Markell signed H.B. 314 into law in 2016, making it illegal for employers to require employees to sign a document waiving the right to discuss salaries with other workers.

Making Fewer Businesses Exempt

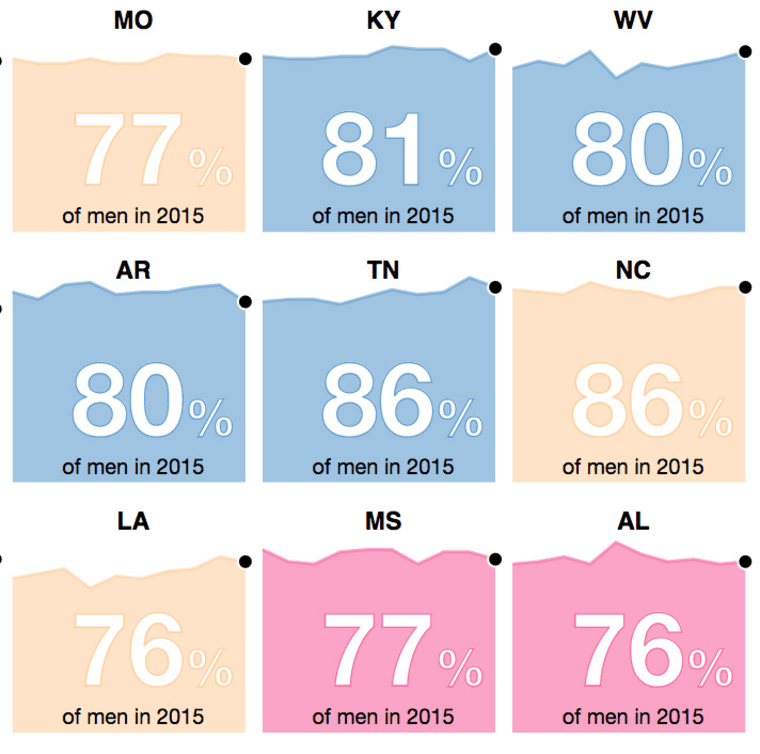

Several states have equal pay protections that don’t apply to smaller businesses or to workers in the private sector, where the wage gap tends to be more pronounced due to a less transparent pay structure. Five states— Utah, Texas, South Carolina, North Carolina and Georgia — exempt small businesses from enforcing equal pay protections, while Louisiana's laws only apply to public workers.

In March, Nebraska amended its equal pay protections to encompass businesses that employ at least two workers per day. Previously, the law applied to businesses with more than 15 workers.

“The bottom line is line is protections need to cover everyone and they need to be strong and robust,” Kate Nielson, the state policy analyst for the American Association of University Women, told NBC News.

But Will State Legislation Be Enough?

On Equal Pay Day, April 4, Congress will reintroduce two pieces of legislation originally brought before lawmakers in 1994 and 1997: the Fair Pay Act and the Paycheck Fairness Act. Both federal bills have come close to being enacted in the past, but have ultimately fallen short.

Nielson believes there will be a renewed push in Congress to pass these measures, which strength penalties for equal pay protections violations, provide greater wage transparency and offer more strict circumstances for when employers may pay women less than men, among other provisions.

“It shouldn’t just be about winning the geography lottery if you get protections. It’s not fair that if you cross a border, you all of the sudden have more rights,” she said. “I really applaud the states for leading the way, but that doesn’t let Congress off the hook.”

Also at the federal level, Martin said business groups are urging the Trump administration to roll back an Obama-era initiative requiring employers to report pay data by race and gender to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which could undermine the agency's ability to effectively enforce pay discrimination laws.

Martin said state action on equal pay is important now, as it is more difficult for Trump to undo progress at lower levels of the government.

"[It's] not absolutely beyond imagination that [groups] could try to do the same on equal pay," Martin said. "I think the blowback would be enormous."