CHICAGO — It took her four years to tell someone she was raped.

The victim, now 24, was assaulted by a distant relative who lived down the block and would frequently come over to her mother's apartment on the south side of Chicago.

But the reason she didn't tell anyone wasn't because she was afraid of her assailant, she told NBC News in a soft-spoken slow voice.

Instead, the pain had to be swept under the rug for more imminent trauma — one commonly felt in many of Chicago's deadliest neighborhoods.

Just after the assault, the victim — whose name is being withheld by NBC News — lost her only brother to gun violence and had to take on the responsibility of providing for her unemployed mother on a minimum-wage job.

"There is always something bad happening to someone, but you got to keep it moving," she said. "Mostly everyone I know is dealing with something," she said.

But at some point, "it does break you down," she said.

Sexual assault is not unusual in Chicago’s violent neighborhoods, but the deadly streets make it difficult to fully recover. Victims not only face the gunfire that continues to whittle away at their communities, but have little access to counseling and other resources. There is widespread distrust of institutions that might be able to help, experts say, and a resistance to appearing weak.

Barriers to Recovery

"Certain environmental vulnerabilities, like high poverty and high crime, leave a lot of structural holes that reduce the opportunity for victims to heal and get help," said Celeste Watkins-Hayes, a professor of sociology and African-American studies and faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University in nearby Evanston, Illinois, citing in particular the lack of counseling services.

Amber Johnson, a medical and legal advocate for Rape Victims Advocates on the west side of Chicago, said many victims don't have cars to get to a doctor or counselor, and are unable to take time off of work in low-paying jobs to get help.

"Sexual assault is nothing new or odd in these neighborhoods, but the means to deal with it is," she said.

Many support systems are already exhausted with dealing with gun violence and gang wars.

"In communities with high volumes of violence, social networks and social supports are already stretched very thin," said Nikki Jones, a professor in the Department of African-American Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

When basic day-to-day survival trumps all, Watkins-Hayes said, sexual assault goes to the back burner.

"There are large numbers of victims who are barely surviving in a low-wage market, so they have to make compromises to their physical and mental health to make ends meet," she said.

Currently, only three organizations provide support services to victims of sexual assault in Chicago, and without a state budget, their funding is already running dangerously low, said Sean Black, the communications director at the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault, a not-for-profit group that brings together community-based sexual assault crisis centers across the state.

"Currently, we have no money from the state, and federal funds come with a lot of strings," he said. "Yes, we need to provide therapy but we also have to be able to keep the lights on in the building to do that," he said.

Much of the city’s focus has been on combatting the carnage that’s visible through bodies and bullets, with limited attention on the other traumas.

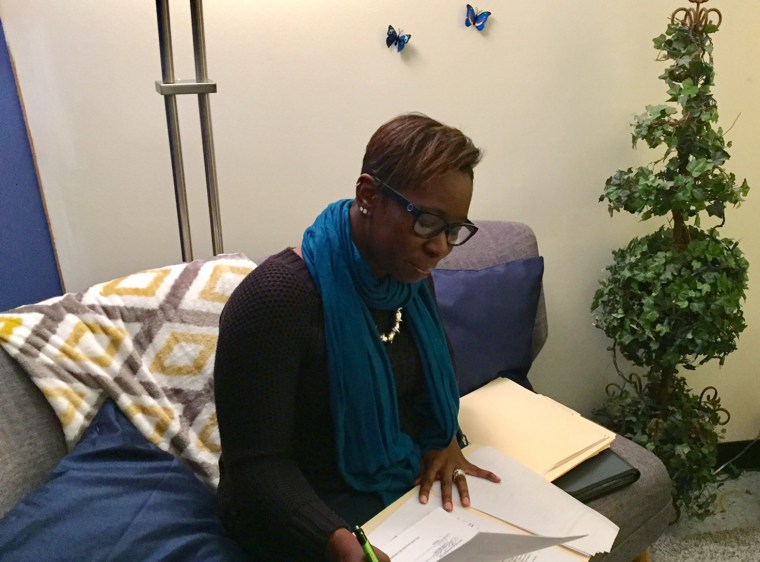

"People who are dying trump those who are living," said DeVona Alleyne, a counselor for Rape Victim Advocates. But just because you can't see the victims doesn't mean they aren't there, said Alleyne, who works out of the organization's office on the west side of Chicago.

Four neighborhoods that consistently ranked in the top-10 for homicide rates from 2002 until 2016 were also in the top-10 for sexual assault rates, according to Chicago Police Department data compiled by the University of Chicago for NBC News.

One of those four, West Englewood, on the south side, tallied 50 homicides last year but also tallied 42 sexual assaults, according to the University of Chicago data.

Holding In The Pain

Last month, a 15-year-old girl from the south side of Chicago was horrifically gang raped on a live-streamed Facebook video to an audience of 40 people, none of whom alerted authorities.

After surviving the brutal attack, the young victim and her mother came home and discovered no comfort from their neighbors, but instead taunts, hecklers, and threats from area residents who found an exploitable Achilles heel in the family.

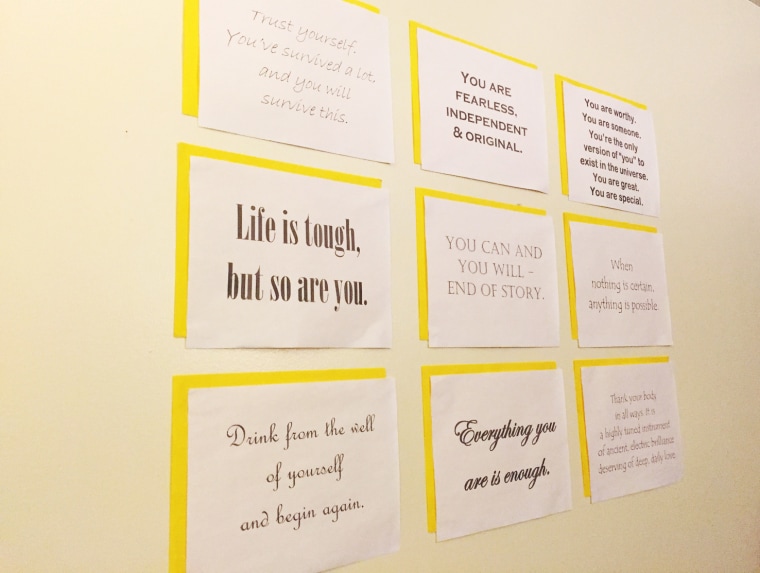

"Survivors of sexual violence frequently feel they have to hold the pain in because if they show it, they reveal vulnerability, which gets you victimized," Alleyne said.

Pain can make you a target, she said.

But pain is a constant reality for a city that, according to the Chicago Tribune, has already surpassed 1,000 shootings so far in 2017, and 180 homicides.

Not coming to terms with that violence will make people more prone to depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and suicide, said Sarah Ullman, a professor of criminology, law, and justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Distrust of Institutions and Victim Blaming

Amid the many police-involved shootings in these neighborhoods, and accusations of police misconduct, a distrust of law enforcement has grown that often stops victims from coming forward.

"Survivors of abuse who reside in communities that have histories and more recent experiences with distrust of law enforcement and limited and absent legal services may be leery about relying on these entities for assistance," Watkins-Hayes said.

"Victims may feel that if they come forward, it may open up an inquiry into their lives or their loved one's lives," she said, and that is something "highly intimidating."

The distrust flows both ways, said Alleyne, who added that officers tend to treat victims from these neighborhoods "different" from others.

"I've seen officers get very aggressive and almost blaming the victim for being in the situation they are in," she said. And because of that, victims feel that if they come forward, law enforcement and even hospital personnel will talk to them in a way that it's their fault because they live in these neighborhoods, she said.

So instead they choose to internalize and keep the pain unattended, she said, rather than deal with the humiliation they feel comes with engaging with law enforcement.

The assault victim said her rape ate her up inside, and after several bouts of depression, she finally sought out a therapist a year ago — one she has to take two trains to visit.

"I wanted to be as far away from home as I could manage, like my own space, where I could get better," she said.

"What do I want people to know?" she asked. "That I'm a survivor, like everyone one else who goes through this. Even though I might have some more challenges, I will overcome."