Imagine this scenario: A terror suspect is holding hostages in a public space. A police-operated drone with a camera swoops in to assess the situation and determines he is armed and dangerous.

The man is coaxed to surrender by a SWAT team, but his posturing suggests he is about to shoot. As a final resort, the drone — toting a firearm — hits the suspect. He is neutralized.

The way some lawmakers in Connecticut see it, weaponized drones represent a future for policing — and could be a necessary option in moments when lives are at stake. That's why a bill making its way through the state legislature would be the first in the nation to explicitly allow police to add lethal weapons to drones.

The bill, H.B. 7260, moved overwhelmingly out of the Judiciary Committee last month and must pass the state's House and Senate before the session ends in early June. It's unclear whether this incarnation will go as far as the governor's desk, lawmakers say, after previous legislation on the topic failed to gain traction in recent years. Civil liberties groups are urging caution on the measure, citing concerns over privacy and when force would be used.

Regardless, the growing prominence of drone technology means ground rules need to be in place sooner rather than later for whether they can be weaponized and to what extent, said state Sen. John Kissel, a Republican co-chair of the Judiciary Committee who supports weaponizing drones. Lawmakers are continuing to discuss the bill.

Kissel said he recognizes that civil liberties groups believe Connecticut could be setting a dangerous precedent, but if civilians are already outfitting their drones with weapons — as what happened in Connecticut in 2015 with a teen's "flying gun" experiment that went viral — then law enforcement has to be given the same advantage.

Related: Eyes in the Air, Guns on the Ground: The Near Future of Police Robots

"We have to be able to fight fire with fire," Kissel said. "The use of weaponized drones isn't going to go away because we don't like it, so we have to do something now."

Kissel said he can imagine a range of scenarios that would allow the high-tech gadgets to be weaponized. They include: dismantling a bomb placed in an area where people cannot reach; shooting down another armed drone; shooting out a tire in a high-speed car chase; or using a stun gun on a suspect.

Any law "would be extremely narrowly tailored," Kissel said, "and we want there to be really rigorous training because of the potential for lethal force under certain circumstances."

State Sen. Paul Doyle, a Democrat who co-chairs the Judiciary Committee and also supports the bill, said he is also on board for its use in limited situations, including a terrorist incident.

"It's an option in (police's) tool box during a serious event. But I don't want to see it used for pulling over a car if the driver was speeding," Doyle said.

At least 347 police and fire departments in 43 states are using drones, including for search and rescue operations, crime scene photography, and surveillance, according to a study this month by Bard College's Center for the Study of the Drone. Departments in Los Angeles, Miami Beach, Orange County, Florida, and San Diego County have at least one.

But researchers say no department currently utilizes weaponized drones, including in Connecticut, where about three police forces have drone technology.

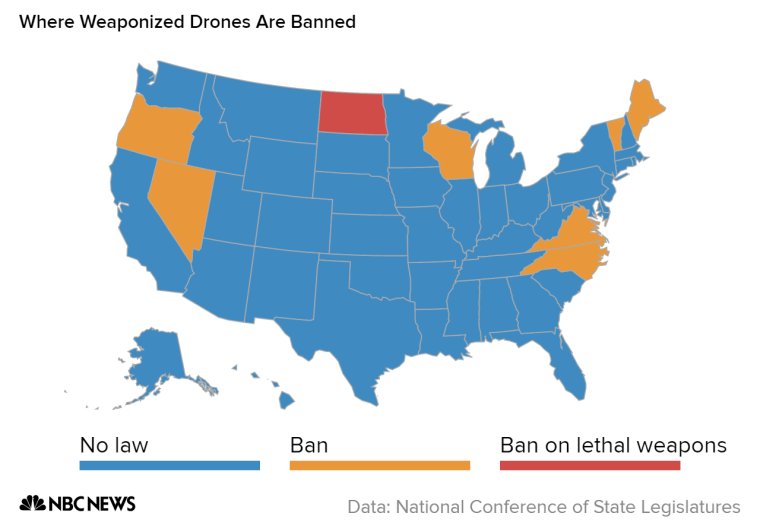

Only one state in the country — North Dakota — bans the specific use of lethal weapons on drones but created a loophole that allows for police departments to employ non-lethal weapons such as Tasers, tear gas or rubber bullets on the devices. No departments in the state are known to be using them, said state Rep. Rick Becker. He was the politician who first introduced legislation to ban all weapons on drones, which was amended in 2015 to only prohibit the lethal options.

Becker continues to argue that drones, also known as unmanned aerial vehicles, should be devoid of any munitions.

"There's a disconnect with a person sitting in a trailer commanding a drone that can hurt or kill," he said. "That's the dangerous, creepy thing about it."

Just five states ban the use of weaponized drones — Nevada, North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont and Wisconsin — while two others — Maine and Virginia — ban law enforcement from using them altogether, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Seth Stoughton, an assistant law professor at the University of South Carolina and former police officer, says states would need to decide explicitly whether they want to institute bans on civilians and police — or find themselves in legal quandaries.

Police departments are already shifting the way they interact with communities with the use of bodycam technology, and drones could epitomize the next stage in crime fighting. Stoughton said the public probably wouldn't have a problem with drone use under certain circumstances, such as barricade situations or neutralizing explosives.

But last summer's decision by Dallas police to strap a pound of C4 explosives to a remote-controlled robot to go after a suspected police killer — leading to his death — raised concerns about how ethical it is to kill with such a delivery system.

It was believed to be the first time that a police force in America killed someone that way.

"Where people will have problems and where agencies need to be cautious is weaponized drones that use force in situations where we're not used to that," Stoughton said.

"Use of weaponized drones reinforces the idea of soldiers engaged in a war," he added. "Perceptions matter a lot to people."

David McGuire, executive director of the ACLU of Connecticut, which is opposed to the bill, said policing is already fraught with controversies over justified use of force, racial bias in arrests and poor engagement in communities of color. Things only become more complicated when drones are thrown into the mix, he added, bringing up questions about privacy and warrantless surveillance.

"The basic idea of a gun or Taser on a drone is, simply put, a chilling sight."

In Connecticut, how police would use weaponized drones would be developed by the state Police Officer Standards and Training Council, according to the bill.

Paul Melanson, the legislative co-chair for the Connecticut Police Chiefs Association, said use of force is already dictated by statewide policies and just because a department might have access to a weaponized drone doesn't mean it can use them haphazardly.

"We need to be talking about this now, because who knows where this issue will be five years down the line," Melanson said. "Pre-Columbine did we talk about active shooters in schools? No. So we have to always adapt to what people might be doing."

He reiterated that drone technology is still expensive — potentially costing tens of thousands of dollars, and plenty of cash-strapped communities don't have the money to spend on them. Still, the number of departments nationwide that acquired drones was just a handful in 2013 to more than 150 last year.

McGuire believes the idea of weaponized drones will be flying into a wave of public backlash.

Connecticut's bill "sends the wrong message to the community. It will make them feel like the enemy," McGuire said. "The basic idea of a gun or Taser on a drone is, simply put, a chilling sight."