President Donald Trump and GOP lawmakers have yet to come up with a plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. But in the meantime, there's already a complicated vocabulary to describe the process and its goals.

The terminology can be difficult to follow, starting with the now-ubiquitous phrase “repeal and replace.” Adding to the confusion is that Trump often makes statements that appear to contradict past Republican health care proposals, either on policy or on the procedure for enacting them, while Republicans insist that no such contradiction exists.

Examples include Trump’s twin promises of “insurance for everybody” and “much lower deductibles;” his stated opposition to any cuts to entitlement programs; and his demand that Congress pass a replacement for Obamacare “simultaneously” with its repeal.

The result is a lot of disagreement over what these various phrases mean, with some experts warning that they are boxing Trump into promises a GOP-authored health care plan can’t realistically keep. At the same time, many Republicans argue the terms Trump uses are just a different way to articulate the same shared goals. There are parallels to the 2013 immigration debate, where legislation was bogged down by battles over what common terms like “amnesty” and a “special path to citizenship” actually meant.

But the confusion also reflects real difficulty in crafting a plan that can satisfy everyone’s demands. The Washington Post obtained leaked audio of a meeting of Republican House members this week that revealed numerous individual concerns about the politics, timing, and substance of a GOP replacement, with no obvious resolution in sight.

As you follow the health care debate, here are some terms that might appear straightforward on the surface, but are actually less clear than they sound.

What is Trump’s Health Care Plan?

Here’s a simple enough question: Does Trump have a plan for health care?

In an interview before his inauguration, Trump told the Washington Post that he had been working on his own proposal and it was “very much formulated down to the final strokes.” But it’s not clear that’s actually the case.

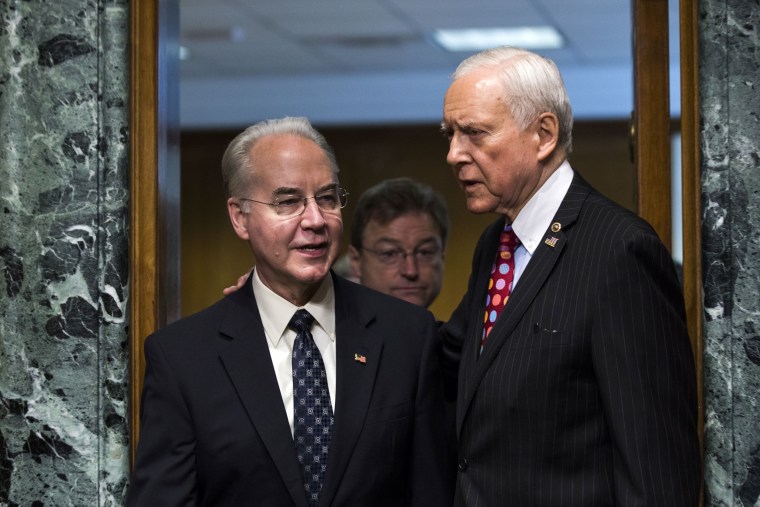

At the confirmation hearing for Tom Price, the Georgia congressman now Trump’s Health and Human Services nominee, Ohio Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown asked Price whether Trump was telling the truth and that his White House would soon release a proposal.

“It’s true that he said that, yes,” Price responded.

After the room broke out in laughter, Price would only confirm he’d had “conversations” with the president on health care.

For now, the House and Senate are taking the lead on efforts to craft “Trumpcare,” but there’s still no agreement on what that legislation will look like and how they’ll get it passed.

What Does 'Repeal' Mean?

Here’s one thing almost everyone involved in the process agrees on: “Repeal” doesn’t mean repealing all of Obamacare, at least not initially. What Republicans typically mean is “partial repeal.”

First, there are elements of the ACA Republicans want to keep. Their replacement plan will likely use some of the same sources of revenue, for example, like reduced spending on private Medicare plans. Some Republicans argue that the repeal bill should leave the rest of the law’s taxes in place too, in order to give them more flexibility on funding its replacement. A GOP replacement plan might also include some popular Obamacare features like allowing young adults to stay on their parents’ plans until age 26.

The bigger obstacle to full repeal are the rules of the Senate. Republicans are planning to pass their “repeal” bill using a procedure called budget reconciliation, which allows them to enact legislation with a bare majority -- there are 52 Republican Senators -- rather than have to overcome a Democratic filibuster, which would require 60 votes.

The downside to this approach is that the rules also limit what can be addressed in reconciliation. Among those untouchable aspects are crucial ACA regulations on insurance companies, including its requirement that insurers accept new customers even if they have a pre-existing condition. The plan for now is to take out large chunks of the existing law, including items like the mandate requiring everyone to buy insurance or pay a penalty. They’d leave the rest for a future bill.

The White House could also take some additional actions to wind down the ACA: Trump has signed an executive order instructing agencies to find ways “to minimize the unwarranted economic and regulatory burdens” from the law but it’s still not clear which changes they’ll pursue.

It’s a sensitive process, because if major parts of the law are removed while leaving its regulations in place, a crisis could ensue in the insurance market, causing premiums to spike and companies to pull out. A GOP bill last year that was considered a dry run for the Obamacare repeal would have caused 18 million people to lose insurance in the first year, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Republicans argued those findings were not relevant because they would find ways to stabilize the market while they transition to a replacement health care system. But, as the Washington Post audio revealed, some members are concerned about the fallout if the initial repeal effort causes people to lose insurance.

“The fact is, we cannot repeal Obamacare through reconciliation,” Rep. Tom McClintock (R-CA) was heard telling his colleagues. “We need to understand exactly, what does that reconciliation market look like? And I haven’t heard the answer yet.”

What Does it Mean to do a Replacement 'Simultaneously'?

Here’s where words start to lose meaning. Trump told reporters this month that he wants a replacement for Obamacare to occur “essentially simultaneously” and perhaps even “the same hour.”

When you hear a phrase like “simultaneously,” you might assume he means that Republicans will have a full bill ready to go as soon as they repeal the ACA, that they’ll pass it immediately afterward, and that the replacement will then become the new health care law of the land.

That’s not what’s under discussion for now. While there’s no agreed-upon plan yet, Republicans have mostly floated a transition period that would maintain the Obamacare exchanges where individuals buy insurance for some time -- potentially several years -- while they work out a full replacement, which could be a long and onerous task.

“It's way more complex than simply 'repeal and replace,’” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) told CNBC. “That's a fun little buzzword, but it's just not accurate.”

House Speaker Paul Ryan described the process earlier this month as one that moves “concurrently” with repeal and others in the party have used similar terms. On Thursday, Ryan told reporters that congressional leaders remained “on the same page with the White House” on health care.

Some senators, including Johnson, have expressed unease about moving forward with repeal without having a replacement ready at the same time. But these concerns can be nuanced too. Republican lawmakers who talked to NBC News have suggested their issues might be addressed by releasing the blueprint of the GOP’s plan and including items like funding for high risk pools or health savings accounts as a “down payment” on a complete replacement. Johnson told reporters this month that he’d like to see “elements of replacement” in any reconciliation bill.

But there are a whole lot of difficult trade-offs and choices that Republicans need to sort out along the way to crafting a plan. And once they come up with their strategy for reconciliation, they face the difficult task of negotiating with Democrats on a full bill, since they don’t have enough Republican votes to overcome a filibuster on a complete replacement.

What Does 'Insurance for Everybody' Mean?

Even though Trump has offered few details on his health care proposal, he made a bold pledge this month that it would include “insurance for everybody.”

“We're gonna come up with a new plan that's going to be better healthcare for more people at a lesser cost,” he said this week in an interview with ABC.

This is yet another area where definitions are unclear. Some conservatives are concerned that Republicans can’t meet Trump’s goal of universal coverage, or even just increased coverage, without spending as much or more than the ACA and imposing new regulations to make sure no one is left behind.

The Congressional Budget Office has not scored the replacement plans proposed in the past by both Price and Ryan, but it’s likely those plans would result in fewer people having health insurance. An analysis of Ryan’s “Better Way” plan by the nonpartisan Center for Health and Economy estimated 4 million fewer people would be insured by 2026 under the bill compared to the current law, mostly due to reductions in Medicaid spending (more on that later).

Both Price and Ryan’s proposals would weaken protections on consumers with pre-existing conditions, which could set up a situation where sick patients who can’t keep up with their insurance payments find themselves unable to afford new coverage later. Some GOP plans seek to address this by funding high risk pools for these types of consumers, but those too would likely require a lot of additional money to be effective.

All this is why many Republicans have been nervous about adopting Trump’s “insurance for everybody” language, talking about providing “access” to affordable health care instead.

But Trump’s not the only one in the party to talk up expanding insurance beyond those who’ve purchased it under Obamacare. Price, in his confirmation hearings, also told senators he “absolutely” shared Trump’s commitment to add to the insurance rolls: “We still have 20 million individuals without coverage,” he said. “I think as policy makers, it is incumbent upon us to say, what can we do to increase that coverage?"

There is at least one Republican proposal Trump could adopt that is explicitly aimed at expanding coverage beyond Obamacare levels. GOP Sens. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Susan Collins of Maine have introduced a bill that would allow states to keep a version of Obamacare or opt into a plan that would automatically provide a new, stripped down insurance plan to everyone unless they decide to opt out or upgrade themselves.

The trade-off is that these more affordable starter plans would be required to cover less than Obamacare, which has a detailed set of “essential benefits” every plan must include along with limits on certain costs. Keep this distinction in mind as we get into another Trump promise …

What Does 'Much Lower Deductibles' Mean?

Trump didn’t just promise insurance for everyone. In the same Washington Post interview, he also promised “much lower deductibles.”

One of the biggest complaints about Obamacare’s individual insurance plans is that consumers have to meet high deductibles before they get reimbursed for expenses, although some preventive services are covered before then.

But Republican plans don’t purport to reduce deductibles, generally speaking, while the ACA sets some limits. The benefit to the GOP approach is that by allowing insurance companies to sell high-deductible plans that cover fewer services, insurance companies could reduce their premiums. But if they decide to instead to set a goal of reducing deductibles while also expanding coverage, insurance would become more expensive. That approach could also end up costing the government more than Obamacare does, by upping the subsidy needed to help people afford a plan.

Some Republicans are choosing to interpret Trump’s “lower deductible” promise to mean he wants a plan that broadly addresses consumer concerns about out-of-pocket costs. They argue that tax-free health savings accounts, where consumers can store money to spend on health care expenses, can do the job.

“What you can do is pair those higher deductible plans with a subsidized health savings account and that can be used to help pay for the deductible,” Collins told NBC News when asked about Trump’s comments.

While an HSA might be able to provide some benefits, it’s still separate from what Trump brought up. That makes this promise something to watch as the debate moves forward.

What Does it Mean Not to 'Cut' Medicaid?

When it comes to Medicare and Medicaid, Trump’s position sounds as clear as could be: No cuts.

“I’m not going to cut Social Security like every other Republican and I’m not going to cut Medicare or Medicaid,” Trump told The Daily Signal shortly before announcing his campaign.

Price told senators at his confirmation hearing that he had “no reason to believe that (Trump’s) position has changed.” Price also indicated that Medicare, the government-run healthcare plan for older Americans, would not be a part of their health care overhaul at all, despite longtime calls by Ryan and other GOP leaders to partially privatize it.

When it comes to Medicaid, the government health care program for low-income people, the definition of “cuts” could be a source of contention.

Trump and Republican lawmakers have separately proposed changing the way Medicaid, which helps states cover lower income residents, is organized.

Right now, the federal government guarantees it will pay states for each individual who signs up for Medicaid. The ACA also provided money to expand Medicaid to people with higher incomes and gave states who decided to accept the funds some flexibility on how to use it. Trump and GOP leaders want to turn Medicaid spending into a block grant instead, which would give states a fixed amount of money at once and even more choices as to how they spend it. Some plans would also give states the option of taking a fixed per-capita amount for each person who participates.

In theory, these changes don’t have to affect total spending. In practice, though, a lot of Republican plans pair block grants with significant cuts over time by increasing funding at a slower rate each year than rising medical costs. Price’s own budget proposal last year would have saved $1 trillion over ten years by block granting Medicaid, according to the non-partisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Republicans also are debating whether they should start Medicaid spending at the level set by the ACA's expansion, which 19 states still have not accepted, or revert to spending levels before its passage.

Critics say these reductions will cut the number of people covered by Medicaid and that private insurance available to them in some replacement plans will require more out-of-pocket costs, putting the burden of the ACA repeal on the poorest customers. Republicans argue states could find ways to be more efficient with less money.

This debate is important, because Price hinted that he may not define “cuts” to Medicaid as “less funding for Medicaid,” despite Trump’s seemingly ironclad wording.

During Price’s confirmation hearing, Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren brought up his previous budget proposal and asked him whether he’d commit to not cutting “one dollar” from Medicaid, given Trump’s instructions. Price disputed the notion that money should be the sole determinant of success, and responded that “the metric ought to be the care that the patients are receiving.”

It was a brief exchange, but it could have enormous implications. Medicaid is more far reaching than many realize: For one thing, it covers long-term care for senior citizens just as a wave of Baby Boomers are crashing into the system. How Trump decides when a “cut” is really as a “cut” could be one of the biggest decisions in the health care debate.