WILKES-BARRE, Pa. — For William Lisman, the longtime Luzerne County coroner, the first sign of the coming plague appeared in the hills of northeastern Pennsylvania in November 2015.

A 27-year-old woman from one of the mountain towns surrounding Wilkes-Barre was found dead in her family home.

Lisman suspected a drug overdose. She was young. She had been healthy. There were no obvious signs of trauma. And heroin abuse had been on the rise in recent years.

“When a person dies of an overdose, the lungs fill with fluid,” he said. “The victims essentially drown in their own fluids.”

Because autopsies are expensive and time consuming, many coroners faced with cases like these do toxicological tests designed to pick up traces of known drugs to determine the cause of death. But the first test Lisman administered came back negative. So did the second.

So Lisman listed the cause of death as undetermined.

Several days later, a 34-year-old man was found dead in a sleeping bag in the nearby city of Hazleton.

Once again, Lisman suspected a fatal drug overdose. Once again, the tox tests came back negative. And once again, he listed the cause of death as undetermined.

“I remember when it started because it was budget time and they were about to cut my budget,” he said, with a wry chuckle. “At that point the doctor I had been consulting with (about these two cases) told me, ‘Bill, there is something going on here’.”

Like many coroners in smaller counties, Lisman is not a doctor. But he knows about death. A third-generation Wilkes-Barre resident, he and his family ran a funeral home that buried several generations of city residents. He reached out to fellow coroners in neighboring counties to see if they had similar cases.

They had. And the answer was fentanyl, a powerful painkiller the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration says is 25 to 50 times more potent than heroin, packs 50 to 100 times more punch than morphine, and can be manufactured easily by illegal drug mills. This was the same drug that killed Prince last April.

“I started hearing about fentanyl and how drug dealers were cutting heroin with it,” he said.

Lisman said he had the toxicological tests “tweaked” to detect the presence of fentanyl and “after that, the drug overdoses here skyrocketed.”

Facing a crisis, Lisman called the local newspaper, The Times Leader, last May and sounded the alarm.

“I knew I wasn’t going to stop people from using, but I wanted people to know what they were using,” he said. “This stuff can kill them.”

And it has.

The deadly math in Wilkes-Barre

Last year there were 137 fatal drug overdoses — more than half of them the result of heroin laced with fentanyl — in a county of just 318,000 people.

That death rate is four times higher than New York City.

“Twenty years ago, we might have 12 deaths we determined to be drug deaths,” Lisman said. “This year we are on track for 150 deaths…By our standards, it’s off the charts.”

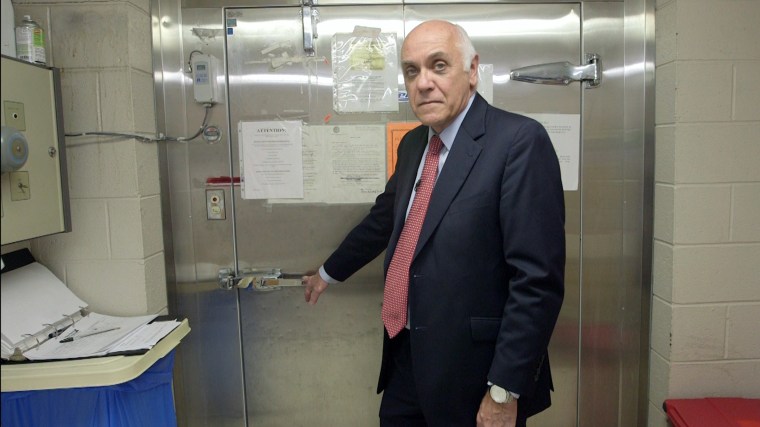

There have been so many fatal drug overdoses that Lisman, who uses an examination room in the basement of a local hospital to do autopsies, said he has had to “finagle space to put all the bodies.”

“I have only room for two in my cooler,” he said. “There’s room for just 10 more in the hospital’s other cooler.”

The victims reflect the demographics of the county — they’re mostly white, often lower to middle income, Lisman said.

“Age wise, we are across the spectrum, from 20s to the 70s,” he said. “We see everyone from the guy in the flophouse to the hard-working guys or gals who find relief in drugs.”

Also, while heroin users in the past relied on needles, “the vast majority now is being snorted,” said Lisman. “A user doesn’t have to go through the process of injecting now. It makes it easier to use.”

A big part of the reason Wilkes-Barre is grappling with a drug problem, Lisman said, is because this city of 41,000 is just a two hour drive from Philadelphia and from New York City. Interstates 80 and 81 converge just south of the city.

A packet of heroin that sells for $5 in the Bronx can fetch double that in Wilkes-Barre, Lisman said. And if it’s cut with fentanyl, the profit quadruples along with the danger to the users.

“Heroin definitely has its hold on this area,” said Cathy Ryzner, a certified recovery specialist at the Wyoming Valley Alcohol & Drug Services in Wilkes-Barre. “I’ve never seen anything like it. Every time you look in the newspaper and you see somebody died young and at home, you know. You know.”

Christopher Emmett buried his 23-year-old son, Christopher Jr., in August, although in his case it was due to a lethal mixture of morphine and codeine.

“Every time I hear of somebody dying it’s always with the fentanyl mixed with it — it’s never somebody that just did heroin and died from doing heroin,” he said.

From boom town to boarded-up storefronts

The plague hit Wilkes-Barre as the proud county seat on the Susquehanna River was struggling to reverse decades of decay.

Once a thriving city of 80,000, Wilkes-Barre was built by coal and manufacturing barons who erected stately homes and public edifices like the stunning Luzerne County Court House and the 14-story Luzerne National Bank Building in Public Square. Thousands of Italian, Polish, Lithuanian and Irish immigrants poured into the city to work in the mines and toil in the garment factories.

But the city lost half its population when the anthracite coal mines died in the 1950s and the good manufacturing jobs began vanishing. And in 1972, Hurricane Agnes delivered a body blow to the local economy when it flooded downtown with nine feet of water.

After that, Wilkes-Barre became a city of abandoned buildings and boarded-up store fronts as the remaining residents struggled to find their footing in an economy where the main employers were now government agencies, the local colleges and hospitals.

The recession in 2008 hit Wilkes-Barre — long a Democratic bastion — hard. And when Barack Obama was running for president, hopeful residents voted for him in droves and did so again when he ran for reelection in 2012. But while the rest of the country rebounded, this Rust Belt city and the rest of the county, including Vice President Joe Biden’s hometown of Scranton, across the border in Lackawanna County, were slow to recover.

Many jobs returned, but not many were the good-paying kind that could support a middle-class life. And those who opted to stay in Wilkes-Barre became disappointed and resentful.

“They want the jobs they had before, not the jobs that are available now,” said Kathy Bozinski, the marketing and communications chief at the United Way of Wyoming Valley. “A lot of good things happened during the Obama Administration, but a lot of the things the folks here were hoping for just didn’t happen.”

In November, Luzerne County voted for Donald Trump instead of Hillary Clinton, handing the Republican a narrow but shocking victory that helped propel him to the White House.

“I hate to use the cliché, but there are a lot of angry white guys in the region who 20 years ago were making decent money,” Bozinski said. “Now they are struggling to pay the mortgage and have a good life. There is a lot of frustration.”

Mary Wallace, who is Lisman’s office administrator, said for many people leaving Wilkes-Barre for a better life somewhere else is not an option.

“It’s hard for people who have been here for generations, whose families are buried here, to pick up and move even if they might be better off somewhere else,” she said. “This is their home.”

The most unhappy place in the United States

Two years ago, a pair of researchers — one from Harvard, the other from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada — concluded that the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre metro area was the most unhappy place in the U.S.

They reached their conclusion after wading through the results of telephone polls conducted by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between 2005 and 2009, including answers to the question, “How satisfied are you with your life?”

Lisman, whose four grown children did not return to the Wilkes-Barre area after finishing college, agreed that they live in a depressed community.

“We have a lot of people who are unhappy with life,” he said. “People using drugs are looking to escape.”

For Lisman, the heroin plague “is a symptom of the way people here feel and have felt for years.”

“I don’t have an answer for opiate addiction,” he said, his smile fading fast. “The pain and suffering that it has caused is unbelievable. It is eating away at the core of society.”

Ryzner said the people she sees are dealing with a host of demons beyond the economic, everything from sexual abuse and broken homes to being raised in households where drinking and drug-taking runs rampant. She’s seen people who get hooked on prescription drugs make the move to heroin.

“But I can’t just blame the doctors,” she said. “It’s a little bit of economics, little bit of hardship, little bit of being raised like that.”

Drugs like heroin, she said, “makes all your problems melt away.”

“It masks any kind of hurt, any kind of feeling…after three days of doing opiates you are addicted,” she said. “You don’t even know you’re getting caught up.”

And Ryzner would know. She was a drug addict for three decades and has been clean for 10 years.

Death by drug overdose 'just not natural'

It was against this backdrop that the heroin plague hit the region.

Coroner Lisman, whose dad was once the mayor of Wilkes-Barre, said that at first he made a point of personally going to the scenes when a suspected fatal overdose was reported. No more.

“Now it’s become so routine,” said Lisman, who has gone back to dispatching his deputies to do the grim work of taking the bodies to the morgue.

But Lisman said he is very much aware of what this plague is doing to his hometown and admits it has left him shaken.

“I was raised in an apartment above a funeral home ... death never scared me,” he said.

What bothers him, he said, is the resignation he has seen in the victims’ families ones who react “almost with relief.”

“It bothers me that somebody’s life could reach a point that death could be a positive thing,” he said.

This from a man who has comforted thousands of people over the years whose loved ones died of natural causes, sometimes after enduring years of pain.

“Death by drug overdose is different,” he said. “That’s just not natural.”

One case in particular still haunts him. The police had gotten a 911 call and arrived to find a young couple in their 30s dead in bed from “a hot load of heroin while their 5-year-old son was watching TV and eating Cheerios,” Lisman said. “He knew enough to call the police for help.”

Death behind closed doors

The heroin plague in Wilkes-Barre is largely hidden with death taking drug abusers behind closed doors.

“You don’t see junkies on the street,” said Bozinski, who was previously an Emmy Award-winning TV and radio reporter. “This happens behind closed doors. In bedrooms and basements.”

But the effects ripple across the city and touch everyone.

“Everywhere you go you hear, ‘Did you see the story about that one in the paper? Was that another drug overdose?” said Wallace. “That’s what everyone here is talking about.”

The toll is not just psychic. Crime is up, police report, especially petty thefts and break-ins by drug abusers looking for money to score a fix. And the dealers are almost always out-of-towners.

“They’re not racist,” Bozinski said of Wilkes-Barre’s residents. “Yes, some white guys blame people from outside for bringing drugs here. But there’s also the acknowledgement that there is a market for it here.”

What’s happening now in Wilkes-Barre is not new. Heroin use has been on the rise across the country since 2002, according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“We’re behind the times," said 42-year-old Paul Smith, who was born and raised in the city — and who buried his former partner Jeremy three weeks earlier after he died of a heroin overdose. “A lot of the problems that were happening in other places are now happening here.”

Sitting in a local bar called Hun’s Café 99 and nursing a beer and a basket of chicken wings, Smith said Jeremy didn’t know what he was dealing with when he started snorting heroin.

“It’s been a very hard thing,” he said. “I spent a lot of time helping him to get clean. It was a very hard reality. And it was very hard to find services to help him.”

Smith said people in Wilkes-Barre turn to drugs because they are already depressed about their lives, depressed that they have to work two or three jobs to get by.

“That’s why people went for Trump,” said Smith, who runs a limo service, owns real estate — and admits to voting for the Manhattan mogul as well. “People are so sick of other people doing better.”

Sitting beside Smith was 28-year-old John Sabatelli. He agreed that it was ignorance of dangerous new variety of heroin that was fueling the crisis. He recalled being surprised when he discovered that a couple at the warehouse where he works was getting high on heroin in the bathroom.

“It’s surprising in that you don’t know who is going to do it,” he said.

Grieving dad Christopher Emmett said drugs have got a death grip on his community. He said his doomed son started smoking pot at age 13 and quickly graduated to harder drugs. He said Christopher Jr. was in and out of rehab — and so were most of his friends.

“It is really an epidemic,” Emmett said. “We went to 14 funerals of my son’s friends who died of addiction in just one year. They’re dropping like flies, every day.”

Emmett’s wife, Patricia, burst into tears at the thought of spending Christmas without her son. And as she cried, her boy’s ashes sat in an urn on a shelf in the living room.

“There ain’t no Christmas,” she said, bitterly.

A proud town fights on

Wilkes-Barre may be down now but it is far from defeated. In Public Square, new restaurants like Franklin’s have opened to serve the young professionals who have moved downtown to live in loft apartments in some of the vintage buildings.

Older establishments like the Café Toscana were bustling with diners on a Tuesday night. And so was the brand new Chick-fil-A, which is located on the first floor of a dorm that King’s College built right on the square in an attempt to make students part of the city’s revival.

Just outside downtown loomed the rotting hulks of long-abandoned factories. But higher up in the hills, Christmas lights twinkled on many of the modest-but-clearly kept up homes and the streets bustled with families going about the business of everyday life.

Over at the ornate county courthouse, which dates back to 1909 and which was built at a time when the future of Wilkes-Barre seemed bright, a chorus of fourth graders from a school across the river in Larksville filed into the central hall to perform a medley of Christmas carols.

Watching them was the grandmother of one 11-year-old, a chubby, brown-haired boy with untied gym shoes. His face creased into an angelic smile when he spotted his grandma.

“I am scared for him,” said the grandmother, who declined to give her name. “I have family that got hooked on drugs. I don’t want that to happen to him.”

Asked why the area has been so ravaged by drugs, she shook her head. “I don’t know, maybe because they’re so easy to get,” she said.

The children’s music teacher, Joseph James, said so far his kids “are completely sheltered” from the heroin crisis unfolding around them.

“I hope it stays that way,” he said.