RIYADH, Saudi Arabia — Dikembe Mutombo may have an easy smile and famous gravelly laugh, but the NBA Hall of Famer does not mess around.

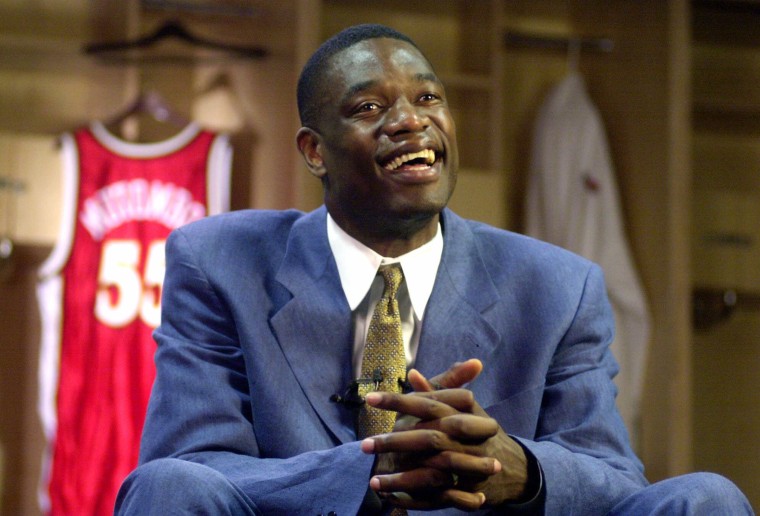

“That African boy does not know how to play basketball,” Mutombo recalls naysayers claiming when he was drafted by the Denver Nuggets fourth overall in 1991.

The Georgetown graduate proved them wrong and went on to become an eight-time all-star and one of most celebrated defensive players in the sport's history.

Mutombo retired in 2009, and traded in his jersey for expensive blue suits.

His mission is now saving and improving lives, not blocking shots. He's using his stature and fame to help some of the world's poorest and most vulnerable.

Mutombo says people told him he was "crazy" when he decided to build a state-of-the-art hospital to help the poor and sick in his native Democratic Republic of Congo.

"You’re a basketball player, get out of here with that story," he recounts being told.

But in Dec. 2007, the Biamba Marie Mutombo Hospital's emergency room, intensive care unit and 150 beds began serving patients in Kinshasa, the capital of his homeland.

The hospital named after his late mother is part of the Dikembe Mutombo Foundation — a multi-million dollar charity that seeks to improve health and education in one of the world’s poorest countries.

It is an understatement when Mutombo says: “If I want to do something and I like it I go for it.”

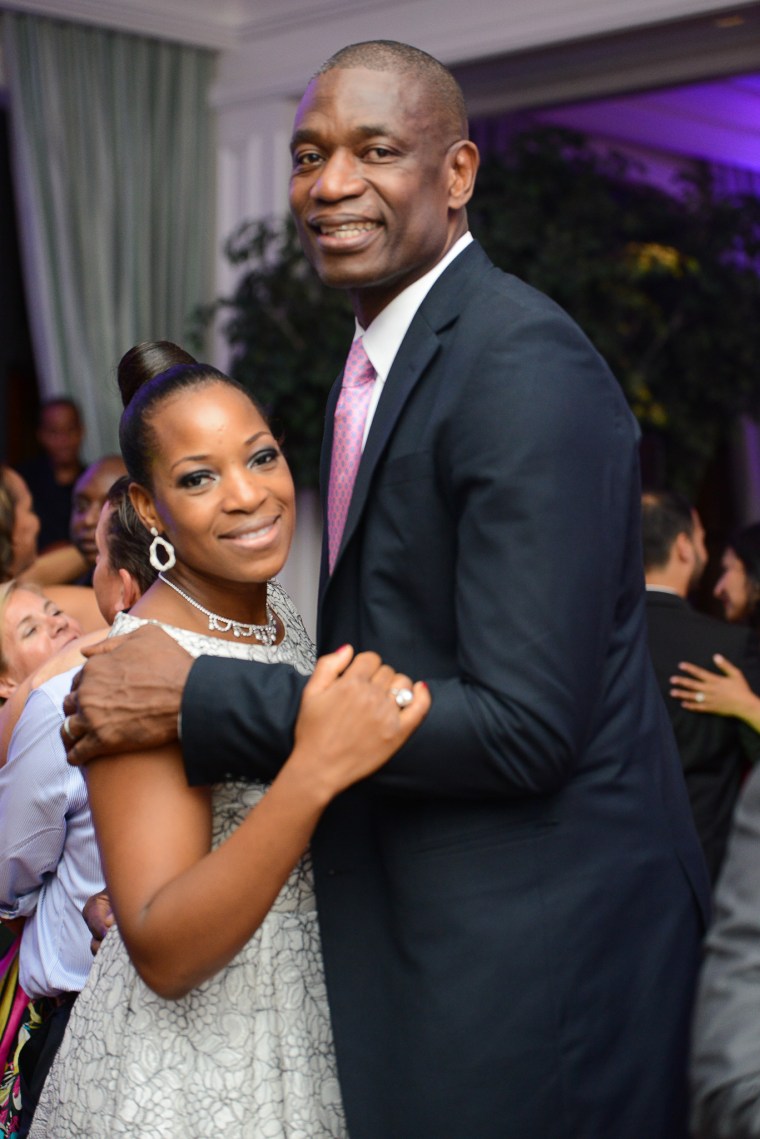

That attitude also defines his relationship with his wife of 21 years, Rose.

She was among a group of English students the 7-foot, 2-inch superstar met during a visit to Kinshasa in 1995.

The future Mrs. Mutombo later told him she had no idea who the giant addressing the class was — she just put up her hand to ask a question.

“She said, ‘Are you married, sir?’” Mutombo remembers.

Mutombo admits he was taken aback but recovered and then turned to his brother who was standing nearby.

"I think I’m going to marry her," he said.

His brother called him "crazy."

Two weeks later Rose flew to America to be wedded to Mutombo. The couple now live in Atlanta and have three children ranging from 13 to 19 years in age.

Mutombo met NBC News in Riyadh, the Saudi Arabian capital where he is a featured speaker at a conference on business and social entrepreneurship.

Folded into chair in the lobby of the Four Seasons, he regaled passing fans with his trademark finger wag and mantra of, “No, no, no, not in my house,” which he deployed during his 18 seasons as a center with Denver, Atlanta, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York and Houston.

"We need to go save our mothers, sisters, grandmas, aunties, cousins"

Now aged 50, his "Mt. Mutombo" nickname still fits him in a lot of ways.

First there’s his height. Then there’s his name — Dikembe Mutombo Mpolondo Mukamba Jean-Jacques Wamutombo.

There is, of course, his storied record as an athlete.

And his baritone laugh makes the air around him vibrate.

But when he talks about his Atlanta-based foundation, the genial NBA global ambassador turns serious.

His work “is all about death,” Mutombo says.

“My thing is about fighting the mortality rate so we can allow the people to live longer,” he told NBC News. “That has been my cause, my drive.”

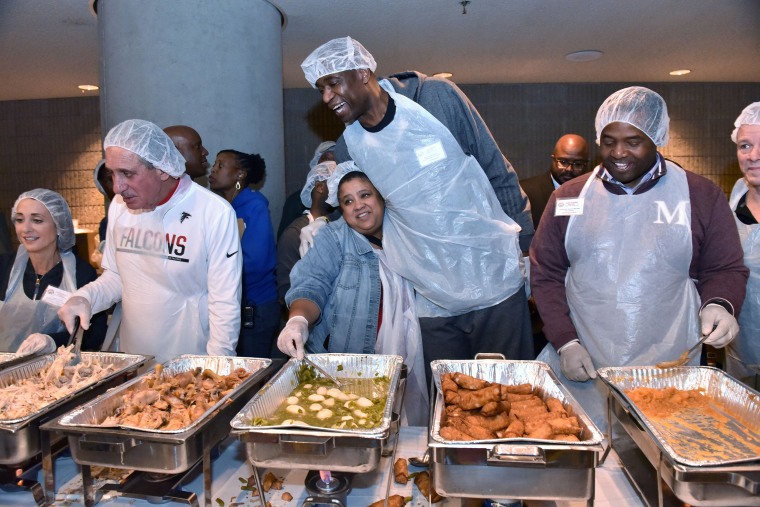

Mutombo says he has contributed tens of millions and much of his time to helping people in developing countries as well as in the United States. He is also a longtime supporter of the Special Olympics.

Mutombo’s own family has not been immune to the violence that claimed nearly 6 million lives during a civil war in the 1990s.

He was in the midst of his successful career when his mother died of a “panic” — most probably a stroke or a heart attack. His father Samuel was unable to get his mother to a nearby hospital because soldiers at roadblocks ordered him and his dying wife back home.

“Then it was impossible for my dad to reach the hospital,” Mutombo recalls.

So Mutombo built the hospital named after his mother, who he remembers as a “wonderful lady, lovely lady” who “kept the door open to strangers and cooked for anybody.”

Mutombo’s commitment began earlier — on the day he was drafted by the Denver Nuggets in 1991.

“I come from a society that is very poor, very abandoned, very neglected by the world,” he says. “I was going from a child who had no dollars in his pocket to suddenly you’re a millionaire … suddenly you got $5 million in your pocket.”

He adds: “It didn’t make me crazy because I come from a place where they say your success is considered a product of the village where you came from — it represents where you come from. The house would not be standing by itself if you didn’t have a strong foundation."

This sense of belonging — to his family, Congo and Africa, as well as the United States — led to his drive to help those who had not been as fortunate.

So Mt. Mutombo moved — he traveled throughout the continent to see for himself what he could do about the violence and disease.

In his quest “to figure out why my people are suffering” he visited Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan and apartheid-era South Africa.

The sense of responsibility comes from being African, he says.

“I see it as a moral obligation. If you’re house has got to be clean, somebody in that house has to take initiative,” he said. “I got sick and tired of people dying on the continent.”

Mutombo is also a man who knows the value of alliances with powerful people.

This ability to make connections is something he honed when he got to know the people who had the money to buy courtside seats during his NBA career. He continues to rub shoulders with the world's royals and pop stars.

He's met and been honored by presidents, including Jimmy Carter, Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton — who calls him an "old friend."

Bush said: "We're proud to call this son of the Congo a citizen of the United States of America."

Mutombo acknowledges such relationships with a simple shrug of the shoulders.

“When you play basketball you’re surrounded by different kinds of people — those are the people you meet you want to know and how they became successful,” he says. "I would not have raised $20 million-plus if I weren’t a good networker."

His most recent venture involves helping drive down Congo’s shatteringly high cervical cancer rates — about 19 million are at risk of developing the disease. So Mutombo and his partners have reached around 10,000 women with a variety of treatments.

"We need to go save our mothers, sisters, grandmas, aunties, cousins," he says.