WARSAW, Poland - Seventy-five years after the Nazis invaded swaths of Europe and carried out the genocide of six million Jews, one Polish Catholic has made it his life mission to ensure the Holocaust is not forgotten.

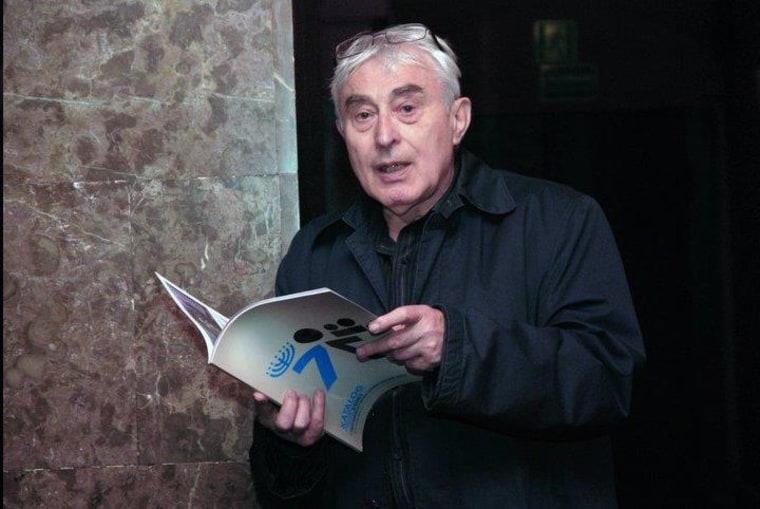

Jan Jagielski used to work as a chemist. But the 77-year-old has become one of the leading authorities on Polish Jewish history, making him the go-to man for Jews traveling from the United States and elsewhere to trace their ancestors.

"My office is a place where people can come to cry and talk about the past," he told NBC News at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. "This makes my life worth living. I make time for everyone."

Jagielski’s affinity to Jews and his interest in the Holocaust began during his high school years in Soviet-era Poland. Many of his schoolmates in his secular school were Holocaust survivors or survivors' children.

Most emigrated from Poland in 1956 and 1968 in response to the discriminatory policies of the communist regime. With all his Jewish classmates gone, Jagielski felt obliged to keep their memory alive.

Around 85 percent of American Jews have Polish roots, according to the New York-based YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. During Jagielski's interview with NBC News, several Holocaust survivors and their descendants visited him. He greeted them with a warm smile and an embrace, listening with patience and compassion.

"He doesn't know how to say no to another human being seeking help"

He began as a hobbyist in the 1960s before joining the Jewish Historical Institute in 1991, traveling the country and recording the location and condition of hundreds of synagogues and 1,400 cemeteries that served the pre-war Jewish population of 3.3 million. He compares pre-war pictures with current ones and has become an invaluable source for anyone looking into Polish Jewish history.

Many synagogues were destroyed by the Nazis, or abandoned and left to ruin. Jagielski helps Jews of Polish descent find cemeteries where their ancestors are buried and also to find their family homes.

"He’s a valuable resource because he has visited almost every city, town and village in Poland to gather information about Jewish institutions," said Poland’s Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich. "And because he doesn’t know how to say no to another human being seeking help."

Jagielski’s archives contain many of the millions of poignant personal stories of the Holocaust. Maria Tyk, 19, wrote a message on the back of her photograph dated November 24, 1942, which was found in a box in the Jewish Historical Institute.

"To the eternal memory for the one who will keep my picture, I am writing on the tragic departure from the family town of Stzegowo," the message said. "Please tell future generations that there were once a people who with full consciousness went to their death, tough people with a great sense of humanity. These people surrendered to the severity of fate. Let my eyes tell you how tragic was my short life."

The next day Tyk was deported to Auschwitz where she was killed.

But thanks to Jagielski’s research, her departing words were published in a newspaper article in 2004, 62 years after her murder.

"This is my eternal obligation to be a guardian of memory"

"It was his way to provide an accurate history of what the Germans destroyed and what the Communists deliberately suppressed," said Menachem Daum, a 67-year-old American Orthodox Jew of Polish ancestry who regards improving the condition of Jewish cemeteries in Poland as a major personal cause.

Jewish visitors come to Poland for historic or sentimental reasons and occasionally to settle restitution claims. Jagielski helps sustain their past, said author Konstanty Gebert, a columnist for Poland’s largest circulation newspaper and a prominent member of Warsaw’s Jewish community.

“He gets great happiness by making a past that many people consider obliterated available,” said Gebert. “In a way, it’s a small victory over Hitler.”

Many Catholics shunned Jagielski’s mother because she was divorced. “She always taught me and my brother to respect people of all religions,” Jagielski said. Her emphasis on tolerance and understanding had a profound influence on him, he said.

Ryzard Mostowicz, a longtime friend, summed up the thinking of many friends: “The history of the Jewish people is his passion. It’s his life.”

For Jagielski, he simply said: "This is my eternal obligation to be a guardian of memory."