The capture of the man accused of leading the deadly raid on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, is more a political and legal victory than an operational one, U.S. officials and Middle East analysts said Tuesday.

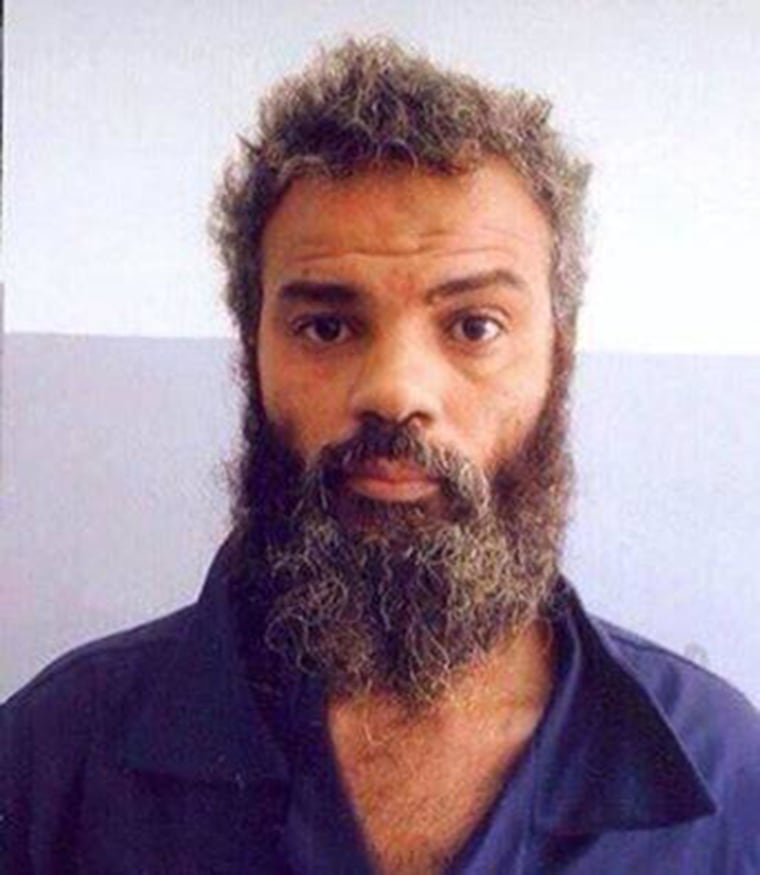

The man, Ahmed Abu Khattala, who is believed to be in his early 40s, faces capital charges in the September 2012 attack, in which Christopher Stevens, the U.S. ambassador to Libya, and three other Americans were killed. He is known to have survived at least one revenge assassination attempt.

Sign up for breaking news alerts from NBC News

Khattala has been described as a top leader of the Benghazi branch of the terrorist group Ansar al-Sharia, which is fighting to impose Islamic Sharia law across Libya. But he was seen as "a simple figure ... not like the current leader" of the larger Ansar al-Sharia structure, Mohammed al-Zawahi, according to Frederic Wehrey, a Libya and Persian Gulf analyst for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Shortly after the attack on the consulate, Khattala began giving interviews all but taunting the U.S. for failing to find and capture him — part of a long pattern of behavior that led other militants to regard him as "an eccentric" at best and at worst "a liability," Wehrey told NBC News in a telephone interview from India.

The U.S. said its operatives were able to swoop in and out with Khattala while sustaining no casualties, which Wehrey said indicates he was not an iconic leader "or has a significant constituency that would rally to his side."

A U.S. official agreed, telling NBC News that the U.S. operation over the weekend was made easier because Khattala was "persona non grata" with the Libyan government.

"He was on the run from both us and them," the official said Tuesday.

In public statements, U.S. officials chose to emphasize the capture of Khattala as a signal of the worldwide reach of U.S. justice over its potential operational value in the battle against Islamist militias.

"It's important for us to send a message to the world that when Americans are attacked, no matter how long it takes, we will find those responsible and we will bring them to justice," President Barack Obama said Tuesday at an event in Pittsburgh.

"I think this is entirely about the objective we had in the country in the immediate aftermath [of the Benghazi attack], to bring them to justice," White House press secretary Jay Carney told reporters. "That's been our focus."

Carney described Khattala only as "a key figure in the attacks," saying he "wouldn't want to characterize" him as the ringleader.

Wehrey said: "I don't even think he's been that active [since the Benghazi attack]. This is really about bringing someone to justice rather than to stop current operations."

Who is Khattala?

Ahmed Abu Khattala has kept his terrorist operations at home in Libya.

Khattala is believed to have been born in Benghazi sometime in the early 1970s. Public accounts and U.S. officials say he spent most of his adult life imprisoned by the government of the late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, which considered him an Islamist extremist.

In interviews with several news outlets, most prominently The New York Times and Reuters, Khattala has said he was a construction worker who never went to college and had never left Libya.

Khattala became part of the militia movement that arose during the Libyan revolution.

In 2011, he formed his own small brigade, called Obaida Ibn al Jarra, which is believed to have been made up of only about two dozen operatives.

While he became influential in and around Benghazi, he was "actually somewhat of a fringe figure in terms of the most powerful militia leaders," Wehrey said.

Khattala rose to prominence that year when Obaida Ibn al Jarra claimed credit for the capture of Gen. Abdel Fattah Younes, Gaddafi's former interior minister who defected to become commander of the Western-backed rebel movement.

Younes' bullet-riddled body was found July 28, 2011, after he'd spent the night in the "judicial custody" of Khattala's group.

Fourteen months later, on Sept. 11, 2012, the U.S. consulate in Benghazi came under a fierce assault. Ambassador Stevens, who was visiting the consulate, was killed, along with Sean Smith, a State Department security official, and Tyrone Woods and Glen Doherty, both described as CIA contractors.

Khattala quickly emerged as the leading suspect. Although he denied having masterminded the raid, he did acknowledge in the New York Times interview that he was present at the scene, and numerous witnesses told The Times he was the one they saw and heard giving the orders.

Last year, the Justice Department filed criminal charges against Khattala in an indictment that remained sealed until Tuesday, when the government revealed that he was charged with:

- Killing a person in the course of an attack on a federal facility.

- Providing material support to terrorists resulting in death.

- Using a firearm in relation to a crime of violence.

He could face the death penalty if he's convicted, which would be a major political victory for Obama, who has come under fierce attack from Republicans for what they see as his administration's failure to secure the consulate and its ineffectuality in responding to the attack.

"I am very happy for the folks who put the operation together," said Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Michigan, a prominent Obama critic who is chairman of the Intelligence Committee. "Well done."

FBI Director James Comey said Khattala's capture sends a message that "we will shrink the world to bring you to justice, and I think this is a good example of that."

"I am very happy for the folks who put the operation together. Well done."

While that's "a very powerful signal," it's one that could have messy consequences, however, Wehrey said.

In the short term, the U.S. operation could drive even more Libyans into the arms of the militias at a time when Libya's government is deeply divided — breakaway Gen. Khalifa Haftar is leading his own anti-jihadist war in and around Benghazi.

"I think the danger is some Islamist factions may see the United States is now a player in this internal struggle," Wehrey said. "You never know if there's going to be some sort of retaliation."

And in the long term, he said, "I think this could send the wrong signal to the Libyans that we care only about terrorism operations."

U.S. officials confirmed that they didn't inform Libya about the operation until after it was over, telling NBC News that Washington didn't believe it could trust the Tripoli government.

"Libya is a country in desperate need of law and national systems," Wehrey said. "It needs an army and the ability to control its territory. I think there needs to be a more holistic approach."

Jim Miklaszewski, Pete Williams and Courtney Kube of NBC News contributed to this report.