A deal hammered out by Russia, Turkey and Iran to set up "de-escalation zones" in mostly opposition-held parts of Syria went into effect Saturday.

The plan is the latest international attempt to reduce violence in the war-ravaged country, and is the first to envisage armed foreign monitors on the ground in Syria.

The United States is not party to the agreement and the Syrian rivals have not signed on to the deal.

It is not clear how the cease-fire or "de-escalation zones" will be enforced in areas still to be determined in maps to emerge a month from now. Here is what is known:

What are the cease-fire terms?

The deal calls on the warring parties to halt the use of all kinds of weapons in the designated "de-escalation zones," including air force flights. Moscow says that includes flight and strikes by Syrian war planes and air raids by the U.S.-led coalition.

What the deal does not cover are areas controlled by ISIS militants and U.S.-backed Kurdish groups. That leaves the U.S. and its allies free to continue the campaign to retake ISIS- held territory. It doesn't prevent frictions between Turkish troops and their Syrian allies from clashing or going after the U.S.-backed Syrian Kurds.

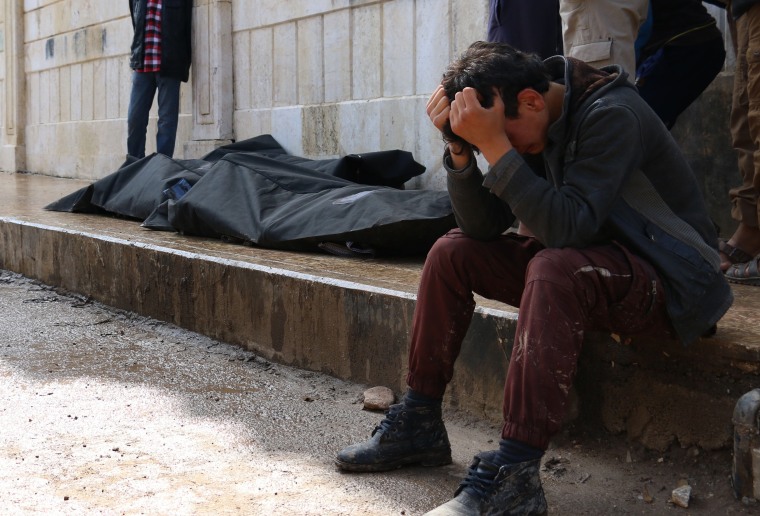

The halt aims to allow humanitarian aid to access hard-to-reach and besieged areas in Syria, were at least 4.5 million people in need reside. The deal also calls for refugees to be allowed to return to the safe zones and services and infrastructure to be restored.

Where are these zones?

Russia says maps delineating the zones should be ready by June 4. So it is not clear how the halt of airstrikes and other violence will be monitored for the month before then.

But the zones, as described on paper so far, are to cover the main battlegrounds in the fighting between rebel forces and Assad's military.

The largest covers northern Idlib province, the opposition-held enclave near the Turkish border, and parts of neighboring Aleppo, Hama and Latakia provinces where fighting has been fierce.

How do the armed observers work?

Previous cease-fires have quickly faltered because of the complex terrain and lack of implementation or monitoring mechanisms.

So under the proposal, Russian, Iranian and Turkish troops will monitor "security belts" on the edges of the "de-escalation zones." Armed forces will man checkpoints and observation points to monitor violations and facilitate movement of civilians. The deal says other nations could join as needed.

The size of such a force is unclear, and its duties are murky, particularly without a U.N. mandate. The important question of who would monitor what areas is unanswered.

And most complicating of all, all three of those countries are already combatants mired in the war, far from neutral "peacekeepers."

Russia and Iran's military support has been crucial to the survival of Assad's government and the victories of his military. Russian warplanes helped bombard rebel areas like Aleppo into submission. Iran's Revolutionary Guard troops have been fighting on the front lines alongside Assad's troops, as well as fighters from Lebanon's Hezbollah and Shiite militias from Iraq.

Still, in a call between President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin earlier this week, the White House said the two had a positive conversation about ways to go about resolving the Syria crisis that included a "discussion of safe, or de-escalation, zones to achieve lasting peace for humanitarian and many other reasons."

Turkey is a backer of the opposition, though its forces have not been fighting Assad. Instead, Turkish troops and allied Syrian factions have been fighting IS militants and a Syrian Kurdish group in the north.

The Iranian role as "observers," formalizing the Iranian troop presence, seems particularly combustible. Rebel factions often express particular hatred for the Iranians and could target their forces. The opposition strongly rejects the idea that Iran can play a role in a cease-fire, accusing the Shiite-majority country of fueling the sectarian nature of the conflict and orchestrating population swaps that amount to demographic change.