Turkey could elect its first openly gay member of parliament in next month’s elections, despite a rising tide of social conservativism in the Muslim-majority country.

The four LGBT activists running include 37-year-old Baris Sulu, who made history once already when he and his same-sex partner applied — unsuccessfully — for a marriage license in a test case that is still going through the courts.

“We are here in this society, we have our problems and we want to be able to have our say,” he told NBC News.

Another candidate is transgender Deva Özenen, who is standing for the recently-founded secular nationalist Anatolia Party. She has been out campaigning on the streets of Izmir, a relatively liberal coastal city.

Homosexuality hasn’t been illegal in Turkey since 1858 — during the dying days of the Ottoman Empire — but it is far from accepted. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the country’s president, has previously described it as a “sexual preference” that is "contrary to the culture of Islam."

Turkey’s military, for which all citizens must carry out a mandatory period of national service, categorizes homosexuality as a mental illness and until recently required intimate photographic evidence or family testimonials from anyone seeking exemption because of sexuality.

But while the inclusion of LGBT candidates on the ballot paper is a sign of growing acceptance, analysts and campaign groups say there is little hope of progress towards ending widespread discrimination or creating legal rights for gays and lesbians.

“There is a degree of acceptance and many [LGBT] people are able to lead normal lives in Turkey,” said Andrew Gardner, Amnesty International's researcher on Turkey. “However, it is a tolerant society but also a country badly served by its government and its media in terms of the negative stereotypes about gay people. There has been a long history of negative statements by public officials and the government is incredibly reluctant to recognize that people have rights or any protection in law.”

Turkey has a visible gay scene, especially in comparison to its Arab neighbors. Istanbul’s annual gay pride march attracted more than 100,000 participants in 2014 — including many attending from other countries in the region where similar events are banned. Role models in popular culture include celebrated transgender singer Bülent Ersoy.

“If you’re out and you’re a celebrity then it is OK but if you’re a normal person you suffer discrimination,” Gardner said. “People have been kicked out of their jobs. A lot depends on people’s socio-economic status.”

He explained that greater visibility and awareness had come from activism rather than state protection.

“The change, where it has come, has come from civil society and LGBT groups,” Gardner addd. “In previous years there was a situation where virtually all [LGBT rights groups] faced closure on grounds of public morality. Largely, this isn’t happening anymore — there are fewer of these cases now.”

References to gay culture are sometimes censored from Western television imports and 85 percent of Turks say they would not like to have gay neighbors, according to the 2014 World Values Survey, compared to 20 percent of those surveyed in the United States.

There are still instances of violence against members of the LGBT community, even as the country seeks membership of the European Union, which upholds equal rights.

In 2008, student Ahmet Yildiz was shot by his father after coming out as gay, a crime billed as a so-called “honor killing.” His case has since been made the subject of a film, “Zenne Dancer.”

And there seems little prospect of change on the horizon. The government of Erdogan’s AKP party has introduced new rights popular with its own support base, such as allowing women to wear headscarves in state-run higher education facilities, but rights for others are not on the agenda.

“I’m very pessimistic about the prospects from this government of bringing [equality] laws into force,” said Gardner. “There was a time, up until a few years ago, when generally there was legislation improving protection for human rights. During the last couple of years generally we have seen new laws presented that actually weaken human-rights protection so the trend is definitely negative.”

Equality is well off the campaign agenda for the June 7 poll, with the economy and nationalist issues instead leading the debate.

Erdogan wants a strong parliamentary majority to push through constitutional changes to create a full presidential system, but with unemployment hitting 11.2 percent in the first three months of the year, some Turks are running out of patience with his AKP government which is leading the polls.

That dissatisfaction could see some tactical protest votes coming to smaller parties, including Sulu’s left-wing and pro-Kurdish party, HDP. It needs to pass a 10 percent threshold of the total vote in order to win any seats, which could leave Sulu with a place in parliament.

“The opinion polls have the HDP on between 9.5 percent and 11 percent, which is within the margin of error,” said Ahmet Han, professor of international relations and politics at the Kadir Has University in Istanbul.

However, the success of either HDP or the Anatolia Party would not be viewed as mandate for LGBT rights in Turkey, he said.

“It would not directly increase tolerance for gay people in Turkey, instead it would be a positive externality of what is mostly an election about the economy and governance,” he said.

Having gay members of parliament “would be symbolic and important,” he added, “but politics in Turkey for the near future will still be about higher political issues and realpolitik, not individual rights.”

Sulu acknowledged the challenges he was facing at the ballot box but remained optimistic. “Unfortunately right now it does not look possible [to get elected] but I opened the door of my candidacy for the next election and I hope we can see LGBT members of parliament within a few years,” he said.

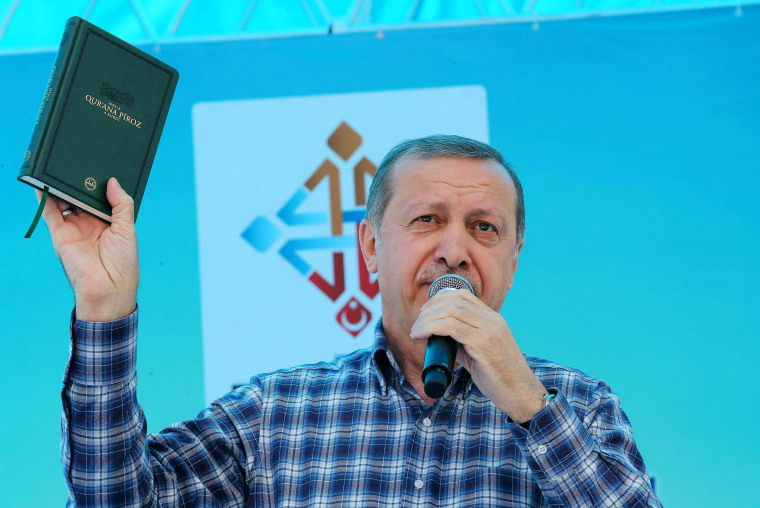

Erdogan’s dominant AKP is rooted in Islam — he has appeared at campaign rallies clutching a Quran — but it is not the sole explanation for Turkey’s conservatism on gay rights.

"There has never been a golden age for LGBT rights in Turkey,” said Amnesty’s Gardner. “The idea of Turkish masculinity and national identity are as important as religion. If you look into civil society there are Muslims who take a very positive stance [on gay rights] and also secular people who take a very negative stance. The idea that religion is the dividing line just doesn’t work.”