The fierce battle over the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch to be a Supreme Court justice ended with an already partisan Senate further divided over lingering grudges and left some members mourning a more collegial time for the upper chamber.

Both Republicans and Democrats were troubled by the dramatic showdown and changes in the Senate rules but also remained hardened by their distrust and frustration with their colleagues on the opposite side of the aisle. In fact, when the votes were called, all but four senators stood squarely by their party's side on the very issues they say could deepen the divide.

Each party made unprecedented moves this week resulting in a change of Senate rules that govern how Supreme Court nominees are confirmed. They even had an apocalyptic name for the change — the "nuclear option" — which eliminated a 60-vote threshold for nominees for the high court.

Related: Neil Gorsuch Confirmed to Supreme Court After Senate Uses ‘Nuclear Option’

The episode was the latest in a long fight over presidential nominations that has left the power of the minority severely limited and feelings raw.

“I think it's a very sad day for the Senate,” said Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who has been part of many bipartisan groups in the past to diffuse partisan stalemates, including one that avoided the “nuclear option” in 2005. “We have now destroyed that 200 years of tradition requiring 60 votes," he said, meaning that the Senate no longer has to "have bipartisan votes to these issues and these appointments.”

Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., struggled with the Democrats' filibuster of Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch, a move that led Republicans to change the rules. It all happened, he said, because there's just too much animosity between Republicans and Democrats.

"In the end, we just don't have enough trust at this point for us to be able to get past this point," Coons said on MSNBC's "Morning Joe."

Related: What is the Nuclear Option and Why Does it Matter?

Sen. Gary Peters, D-Mich., agreed. He has been in the Senate for just over two years but he served in the House of Representatives for four years before that.

"The Senate is much more collegial than the House," Peters said. He says this week's episode will have a negative impact on the Senate.

"It certainly changes the institution of the Senate where you try to find common ground or consensus," Peters said.

And some fear that this is not the end but just the next step in a series of actions that completely changes the function of the Senate. Now that there is no 60-vote threshold for any presidential nominee to pass, some lawmakers say that the same threshold on legislation is next on the chopping block.

McCain warns about that “slippery-slope.”

“Next it will be the legislative 60-votes,” he said.

The filibuster is critical because it gives the party in the minority a tremendous amount of power. One senator can block any legislation from moving forward until they can come to an agreement on a way to move forward.

Coons is so concerned about preserving the institution that he is circulating a letter with Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, to Senate leaders, urging them to keep the filibuster for legislation. Sixty-one senators have agreed to sign.

"We have a long way to go to heal the wounds between our two parties, but this letter is a small first step towards that important goal," Coons wrote.

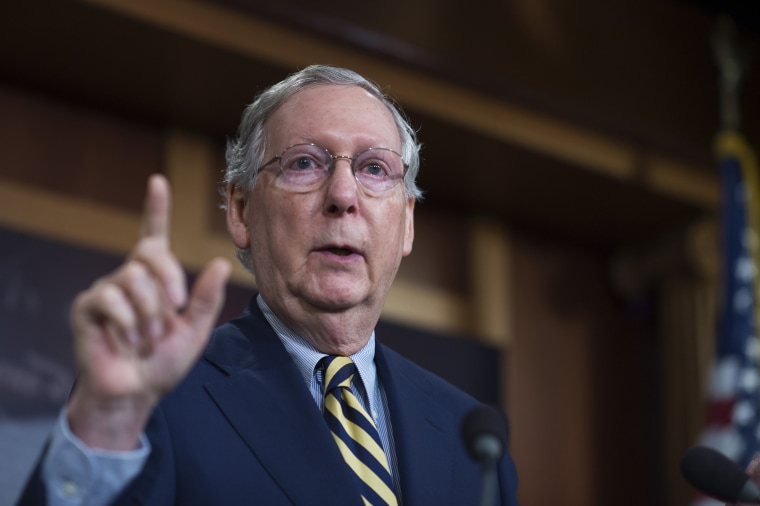

Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said earlier this week that there is “not one” Republican senator who wants to change the legislative filibuster.

“We all understand that's what makes the Senate the Senate,” he said.

Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch predicted that would never happen.

“If we do that, the Senate would become like the House,” he said. “The Senate is a place of deliberation it’s not a place where you can quickly move things through, and the filibuster rule is a very great protection for the minority (party).”

But Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, didn't dismiss the possibility of getting rid of the filibuster for more than presidential nominees.

“At this point there is not a majority for ending the legislative filibuster. My hope is that Democrats will stop their unreasonable across-the-board obstruction and allow the Senate to operate,” Cruz told reporters.

But he added, “if they continue on with an immovable blockade, I suspect the votes will shift on that question as well.”

In spite of this week's bitter fight, many Senators say the upper chamber hasn't been broken. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, told reporters that it’s not going to stop him from working to pass bipartisan legislation.

"I'm of the view that it actually reminds us of how important it is to get along when we can get along," said Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Missouri, and a member of a Republican leadership. "We'll see. The appropriations process will be a test of whether members want to get back together and get something done or not, and I'm optimistic that things can really happen."

Hatch, who has been in the Senate for four decades, wasn’t too worried about the overall impact of the Senate.

“I’ve seen the Senate broken before and we always come back. Hopefully this won’t cause too much consternation,” Hatch said.