COLORADO SPRINGS — The Republican health care plan might be stalled in the Senate, but the bill's proposed cuts in Medicaid spending have spurred a backlash from activists like Kelly Stahlman, who say they would hurt the most vulnerable Americans.

And Stahlman is telling her personal story to try and persuade lawmakers in her home state and beyond that the health care debate is more than a numbers game.

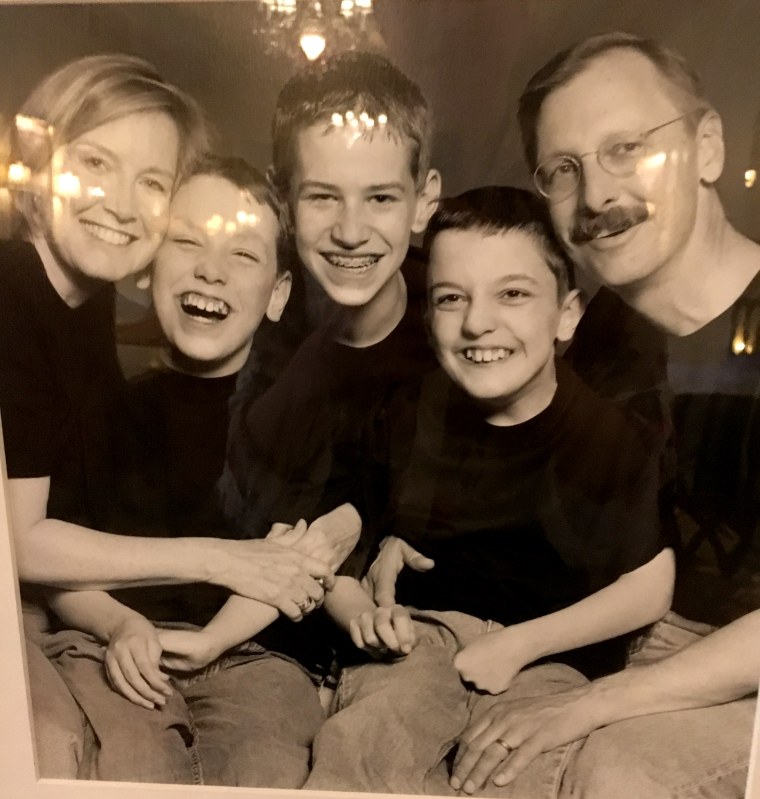

Stahlman's twin sons were born 12 weeks prematurely in 1992, and soon after, both were diagnosed with cerebral palsy and other severe health issues that required around-the-clock care.

After two years of constant care with the help of neighbors, friends and au pairs, Stahlman and her husband, Bruce, found themselves nearly broke — both financially and mentally, she told NBC News.

She says their search for assistance to help with the medical bills yielded nothing and even included advice to seek a divorce and give her twins up to foster care so they could receive adequate help.

Both sons required care that private insurance wouldn't cover at a cost the middle-class family couldn't afford as the bills reached hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

"We weren't poor enough" to get financial assistance, she said, "not in the right county. No matter where I went or what I did we couldn't access anything."

Stahlman says she was so hopeless she even considered ending her life because she felt like an obstacle to getting the care her twins required.

After two years of searching, Stahlman finally received news she said changed her life — her family had qualified to receive Medicaid assistance after Colorado expanded its budget. Mark and Eric moved off a seven-year long wait list to receive the daily care they needed.

“I broke my life into two parts," Stahlman said. The first two years had been "the business of disability." After receiving Medicaid assistance, that turned into a job of "loving on my kids.”

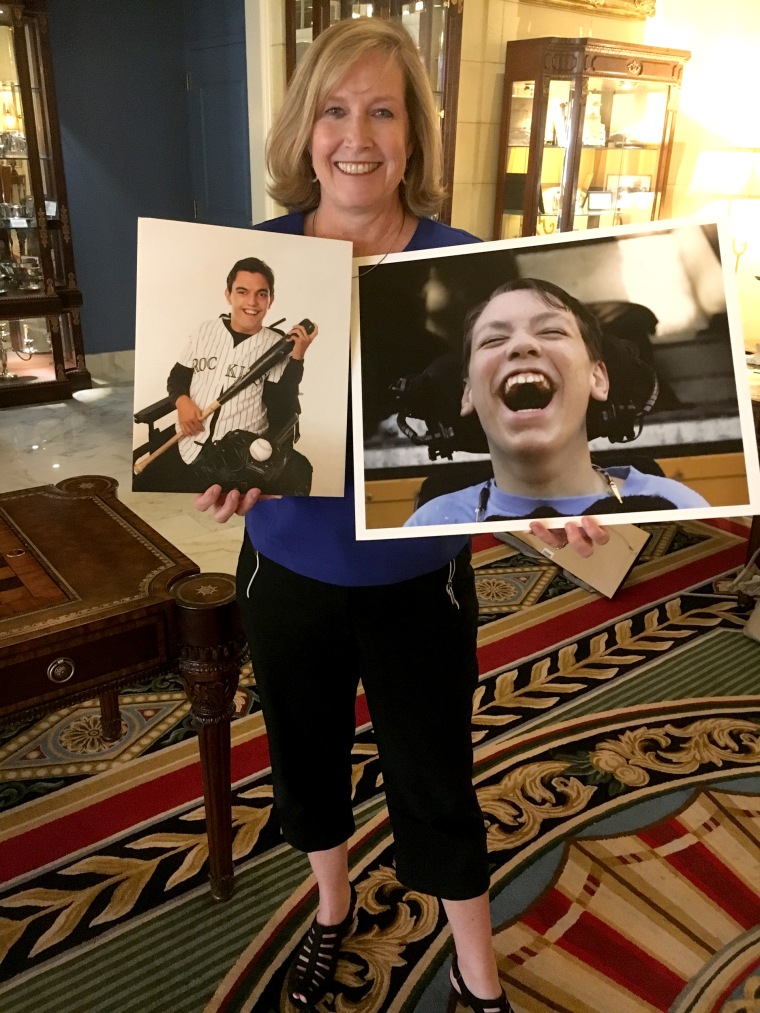

Stahlman said her sons lived full, though shortened, lives. They coached sports, went to school and had girlfriends. Eric proposed to his girlfriend three weeks before his death at the age of 23 in 2015 due to complications from his health issues. Mark “was at the top of his game” when he died in 2014 at the age of 22 after a blood clot that is almost always fatal and usually occurs In the elderly.

“Literally one heartbeat to the next heartbeat, your life changes," Stahlman said, through tears. "There’s before and there’s after and your life is never the same."

Stahlman remains active in advocating for the disabled community in Colorado and her personal journey is the reason why she is vehemently opposed to the Republican health care bill, particularly its cuts to Medicaid.

Medicaid is not just a program just for the poor or unemployed. Sixty percent of adult Medicaid recipients work for employers who don’t provide health care or they make too little to qualify for Obamacare subsidies. Most of the other 40 percent are either elderly or disabled.

Some Republicans have long sought cuts to the entitlement program, which costs more than $550 billion per year. They argue that the program is bloated and inefficient.

Tim Phillips, head of the Charles and David Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity, a conservative group, argues that Medicaid isn’t effective for those who rely on it, especially after it was expanded in 30 states and Washington, D.C. to include more people, under President Obama.

“It has crowded out care for those who are truly the most vulnerable,” Phillips said.

Proponents of the program disagree. Margaret Murray, chief execitive of the Association for Community Affiliated Plans, said that Medicaid is a lifeline for working and the disabled.

"That’s just a specious argument. It does tend to pay less (to providers) but that’s one of the reasons it’s an efficiently run program. Its cost are lower than commercial care," Murray said.

The Senate bill cuts $770 billion to Medicaid over the next 10 years by winding down the Obama-era Medicaid expansion starting in 2021 and implementing a funding cap based on population instead of need. And the bill creates even deeper cuts beginning in 2025 when it changes the funding allocation to rise with general inflation instead of the cost of medical care, a much slower increase.

Some Republicans are pushing for less-drastic cuts to the program. But those efforts aren't enough for activists. "There's no negotiation that can change the core of this bill, which decimates Medicaid," Stahlman said.

The Senate bill attempts to protect children like Mark and Eric by ensuring that they are protected from funding cuts. It was a requirement requested by Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, head of the Finance Committee, which is helping to write this bill, and a host of other senators. But Stahlman said the carve-out for children with complex medical needs doesn’t do enough

When children turn 18 they become adults and their protective status will disappear but their disability and health care needs won’t. Those individuals go to the back of the waiting line and, Stahlman argues, these new adults will see cuts to services and eligibility that will generate new waiting lists.

“Kids grow up,” Stahlman said.

CORRECTION (July 2, 2017, 5:40 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated the year when Stahlman’s twin sons were born. It was 1992, not 1981.