WASHINGTON — It's crunch time for health care in the Senate, where GOP leaders could bring up a bill soon that would partially repeal and replace Obamacare. But the process is taking place behind closed doors and it's often hard to keep track of what's going on amid major news developments elsewhere. Here's what you need to know about where things stand, which lawmakers could make or break a deal, and which policies might end up in a final bill.

Remind me what's going on with health care?

The House passed the American Health Care Act in early May in a dramatic and sudden vote after abandoning a similar effort in March. Now it’s in the hands of the Senate, which has been hammering out its own legislation with a small and secretive working group of Republicans. Because they're using a procedure called budget reconciliation, they can pass a bill with a bare majority — meaning they don't need votes from Democrats, none of whom are likely to support their bill. If the Senate passes something, lawmakers will have to find a way to reconcile their differences with the House to get a bill to the president’s desk.

Is the Senate going to pass a health care bill soon?

They sound close. Republican senators say they hope to pass legislation before the July 4 recess, which means a vote could come within the next two weeks. There's no firm deadline, though, and it's quite possible the process drags on longer. There are 52 Republican senators and they can only lose two votes, so getting to 50 won’t be easy, but members sound more optimistic that they can reach a consensus than they did just weeks ago.

So what’s in this bill they’re so close to passing?

Here’s the thing: We have no idea.

Republican leaders have been negotiating the measure in secret, with talks led by a small 13-member working group that’s consulting with the broader GOP caucus, and leaks are few and far between. Even though a bill may be coming to a vote in two weeks or less, there’s no draft floating around to evaluate or even an outline of the legislation's main features for the public to consider. Rank-and-file members say they’ve still only seen a broad menu of policy options in their meetings, rather than a concrete plan with legislative language.

This is a stark departure from the ordinary process, including the one used to pass the Affordable Care Act in 2009 and 2010, which is to have relevant committees draft legislation while holding public hearings with key industries, patients who might be affected by a bill, and policy experts who can weigh in on the details. The House took a similarly secretive approach with their own bill, which they voted on within 24 hours of releasing final text and without an assessment of its cost or impact by the Congressional Budget Office.

Even some Republican senators complain that they’ve been kept in the dark — Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) jokingly asked NBC News to find him a copy of the bill — and some have said that they’d prefer a more open approach. But so far their grumbling hasn’t translated into action that would force the drafting process into the open.

Are there hints of what's in the bill?

Based on interviews with senators and their public statements, we can get a loose sense of some of the policy debates going on between members, even if we don’t know all the specifics.

It’s likely the broad formula for legislation will be similar to the House bill, which offered less generous subsidies to buy insurance and pay out-of-pocket costs than Obamacare, cut Medicaid significantly and changed its structure, and used the savings to eliminate taxes that primarily affect wealthy Americans and the medical industry. Like the House bill, the Senate plan is expected to eliminate the individual mandate requiring everyone to buy coverage or pay a penalty.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated the House bill would spend $1.1 trillion less on health care and reduce deficits by $119 billion over a decade. But the effects on the individual insurance market would be dramatic: 23 million fewer people would have insurance in 10 years versus current law, premiums would soar for older and low-income Americans, and many customers would face higher deductibles and out-of-pocket-costs. On the flip side, some younger, healthier and higher-income customers could find less comprehensive insurance at cheaper rates.

Republican senators declared the House bill dead on arrival and it’s likely they produce legislation that’s somewhat less far-reaching in its cuts or spaces them out over more time. President Donald Trump publicly embraced the House bill when it passed, but then called it “mean” in a meeting with GOP senators last week and suggested on Twitter he was open to spending more money on care.

Who’s most likely to vote against a bill?

The toughest moderate votes at the moment appear to be Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), who have a wide range of objections to the House bill. Alaska has astronomically high healthcare costs compared to the rest of the country, which makes it a somewhat unique situation. The toughest conservative votes appear to be Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), who may be impossible to win over, and Mike Lee (R-Utah), who is taking a more active role in talks.

Various other senators have raised concerns as well and should not be taken for granted as "yes" votes, but they usually sound more amenable to passing a bill in the end. As was the case in the House, don't be surprised if some members make noise about voting "no" at the last minute as a prelude to cutting a deal that addresses one of their complaints.

What are the biggest issues they need to work out?

One visible area of contention between camps is how much to spend on Medicaid. The House bill would end Obamacare’s expansion of Medicaid and change its funding formula to cut the program further, eventually reducing overall spending by over $800 billion.

That would blow a hole in state budgets that could force them to raise taxes, cut spending elsewhere, or reduce benefits for common Medicaid beneficiaries like nursing home residents and people with disabilities. On Friday, a bipartisan group of governors, including Republicans John Kasich (OH), Brian Sandoval (NV), and Charlie Baker (MA), wrote a letter warning the House’s cuts were too deep.

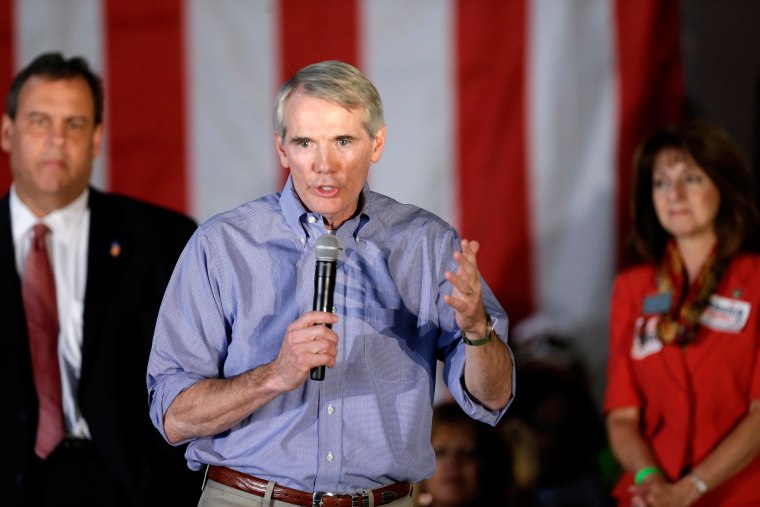

There’s almost no chance the Senate keeps Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion. But some more moderate members in expansion states like Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W. Va.) and Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) are backing a more gradual drop-off, perhaps as long as seven years. Senators in states that aren’t taking Obamacare’s added Medicaid dollars want a shorter transition, like the House bill’s three years. They also have to decide how fast Medicaid grows in the future. Conservatives like Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) are looking at changing the formula in a way that could cut spending even more than the House bill, while moderates want it at higher rates.

Then there’s the question of how generous to make tax credits for people buying private insurance on the individual market. Some Republican senators, including Senate Republican Conference chairman Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), say they want to provide more aid to low-income and older customers than the House, but how and by what amount is not clear.

Another tense issue is how to handle people with pre-existing conditions. The House bill would let states drop Obamacare’s requirement that insurers charge people the same rates regardless of their health status. It would also empower states to waive Obamacare’s requirements that insurers provide certain “essential health benefits” like hospitalization or maternity care. Conservatives argue these moves help lower premiums, but some members are concerned they’ll leave sick people without needed coverage. The CBO predicted the House bill's changes would cause markets to become unstable for people with pre-existing conditions in states that dropped Obamacare's rules.

Some Senate Republicans, including Collins and Murkowski, say they’re worried about leaving too many people without coverage. One idea that’s in play, championed by Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), is to auto-enroll people in a cheap high-deductible plan and give them an option of pulling out. Conservatives are wary of the proposal, however.

Abortion politics could be another sticking point: Murkowski and Collins both oppose a measure in the House bill that would cut off Medicaid payments to Planned Parenthood. The federal government is already restricted from paying for abortion, but the group receives money for preventive care.

Finally, there’s the question of how to pay for everything. The more generous the bill gets, the more taxes lawmakers need to keep or replace with new ones. The budget reconciliation process they’re using requires them to match the House’s $119 billion in overall savings, making this an especially pressing concern.

How is Obamacare doing in the meantime?

Things are getting rough in some states, but there’s a lot of political argument going on over the cause.

In recent weeks, a number of insurers have announced they’ll pull out of Obamacare exchanges in states like Ohio, Kansas, Missouri, and Iowa or raised premiums by significant amounts. Some insurance plans have also stepped in to fill gaps, but there’s a real danger that certain regions could have no insurance options at all come 2018.

This is a continuation of a trend last year as well and Republicans have cited it as evidence Obamacare will collapse without a complete overhaul. But Democrats say the real issue is sabotage: Outside private analysts and the Congressional Budget Office observed that the market was stabilizing this year and insurers themselves say a lot of their turbulence stems from threats by Trump and Congress to withhold payments they’re owed for covering low-income customers’ expenses, known as cost-sharing reduction (CSR). The slow and opaque process of passing a health care bill and questions about the White House’s willingness to fully administer Obamacare is also an issue.

A study by consulting firm Oliver Wyman released last week concluded that the overall uncertainty is likely to cause premium increases of 28% to 40% for the 2018 enrollment period. They also surveyed insurers and found that 42% said they planned to withdraw from the individual market if the government refused to make its CSR payments.

Even if Congress decides it can’t pass a full Obamacare replacement, they may have to pass a short-term measure to stabilize the market. But with insurers making decisions about premiums and whether to offer plans, it may already be too late to avoid some pain for customers next year.