WASHINGTON — Where GOP House members stand on the issue of tax reform can largely depend on where they’re from, a dynamic that is pitting Republicans against each other as they work toward passing an overhaul of the tax system.

Republicans hailing from larger states, which tend to have higher overall tax burdens and costs, have found themselves in a fight for their constituents, who are poised to be some of the biggest losers in the GOP tax bill.

Rep. Lee Zeldin, R-N.Y., who represents parts of Long Island, says the tax bill as proposed is a “geographic redistribution of wealth," taking more away from the many to give to the few.

The most contentious divide is on the Republican-named Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which would eliminate much of the state and local tax deduction, a popular deduction for residents in states where the cost of living is high and so are the state and local taxes.

For example, a resident in Zeldin's district pays nearly $22,000 a year in state and local taxes. But a resident of Janesville, Wisconsin — House Speaker Paul Ryan's district — pays around $11,000 in state and local taxes, according to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation.

Under current law, residents in both states are able to deduct that amount from their federal taxes. But under the proposed bill, much of that deduction would be eliminated, angering Republican representatives in states like New York and New Jersey, whose voters would likely end up paying more.

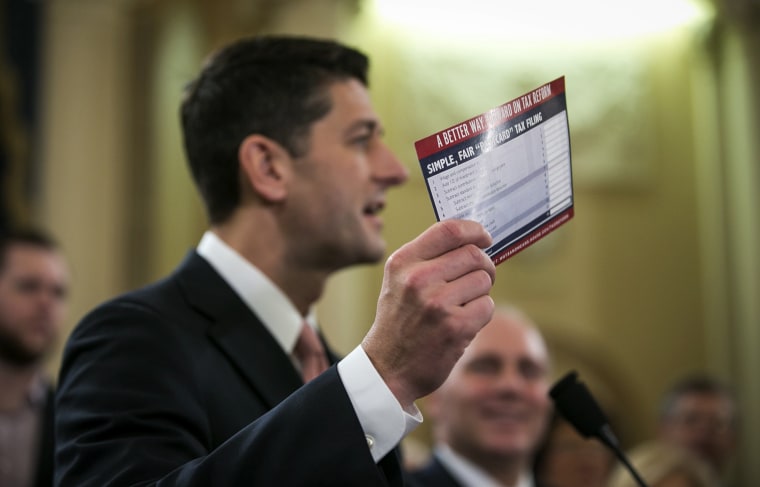

Many Republicans note that just 30 percent of taxpayers itemize their taxes and benefit from that deduction, and they argue that doubling the standard deduction, which the GOP proposal does, will both make up for the losses and benefit taxpayers who do not itemize.

But people with higher incomes do tend to itemize and getting rid of the deduction would mostly affect people making $100,000 to $200,000 per year. And those income levels mean different things depending on where those taxpayers live, opponents of eliminating the deduction say.

“In other parts of the country they might be living the good life. On Long Island, they’re barely getting by,” Zeldin said.

In Zeldin's district, the median cost of a house is $430,000, while in Ryan's it’s $145,000. The cost of child care in New York averages about $15,000 per year compared to just under $10,000 in Wisconsin.

After the first outline of the GOP tax bill, released in September, included the complete elimination of the state and local tax deduction, Rep. Tom MacArthur, R-N.J., launched what he calls an effort to “change the narrative.”

Many of his Republican colleagues have argued that, because of the current deduction, those in states like New Jersey have essentially been subsidized by states where the state and local taxes are lower. But MacArthur says that’s not true, noting that states like his receive less money from the federal government per capita.

“We not only pay for our poor people, we pay for other states’ poor people. And our taxes go up locally, and theirs go down locally,” MacArthur said. MacArthur showed up to one GOP conference meeting with a chart to hand out to his colleagues proving his point. GOP leaders, he said, were not pleased.

“It wasn’t the party line,” he said.

But MacArthur and like-minded lawmakers have continued talking their colleagues. He, along with other New York and New Jersey Republicans, also sent a message by voting "no" on the leadership’s budget, which was a necessary precursor to tax reform.

“Paul is an ideological leader, and I think part of it was him realizing there’s a legitimate perspective from these people,” MacArthur said of Ryan. “It’s not necessarily one that he agreed with, but I think realizing that it was a legitimate perspective combined with the fact that we were voting 'no' on his budget ... ”

The following few weeks consisted of ongoing discussions among Republicans concerned with the elimination of the state and local tax deduction, the GOP leadership and the White House to ensure that their constituents didn’t bear the brunt of a tax reform bill that has to also accommodate a 15 percent tax cut for corporations, a proposal costing $1.5 trillion.

The compromise that made it into the bill allows taxpayers to continue to deduct up to $10,000 of their property taxes, an idea MacArthur says might be enough to gain his support, although he wants that limit to increase with inflation.

But it hasn't been enough for others — five of the 14 New York and New Jersey Republicans have already come out against the bill.

“It specifically targets some areas to take money from in order to pay for deeper tax cuts elsewhere. And that’s why that part is a little bit more of an issue for me,” Zeldin said.

House Republicans are moving quickly to finalize details of the legislation. They began their process of amending the bill in the Ways and Means Committee on Monday, which could last four days.

To complicate the issue, there’s no guarantee the Senate will care about state and local tax deductions. There are no Republicans representing states with higher rates like New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, California or Illinois in the Senate. And a spokeswoman for the Senate Finance Committee said that the state and local tax deduction will likely be eliminated in their version.

House Republicans say they’ve already addressed that concern with their own leadership.

“(Ways and Means Committee Chairman) Kevin Brady and the speaker understand that if they don’t get that done in the Senate, they’re just going to move us back to ‘no’ on a combined bill with the House and the Senate,” MacArthur said. “So they know they have to sell this with the Senate.”