A majority of Democratic voters want President Donald Trump impeached, and, in at least one poll, a plurality of all Americans want the impeachment process to begin. And, regardless of their own opinion on the matter, nearly three out of four voters expect that Democrats will move to impeach Trump if they take back the House this fall.

But, of course, Democratic leaders want nothing to do with this conversation, even as Trump and his allies frantically try to bait them into it.

Each party's posture is understandable when you consider the earth-shaking upheaval that ensued the last time a full-fledged impeachment drive was launched on the eve of an election.

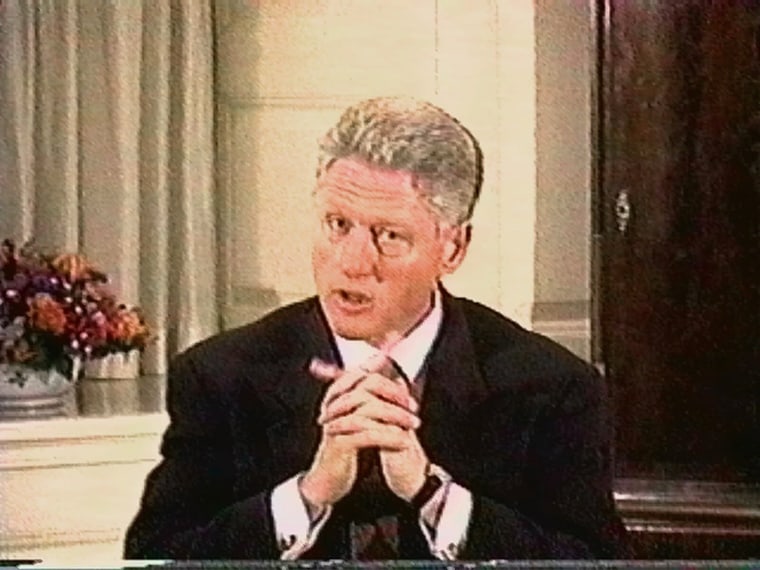

It was Oct. 8, 1998, less than a month before that year's midterm, and House Republicans were poised to use their majority to begin the impeachment process against President Bill Clinton.

Weeks earlier, Ken Starr, the independent counsel who'd been investigating the Clintons and their associates for four years, had filed a report with Congress accusing the president of 11 impeachable offenses. The charges, which included perjury, obstruction of justice and abuse of power, stemmed from Clinton's concealment of his affair with a former White House intern, Monica Lewinsky, a relationship he'd adamantly denied in public and only confessed to after months of sleuth work by Starr's team.

Conservative activists greeted the Starr report with moral revulsion and political determination. Since Clinton's victory in 1992, his electoral endurance had flummoxed them. Now, after years of watching him wriggle free of one jam after another, they finally had "Slick Willie" dead to rights — or so they wanted to believe.

When the Christian Coalition held its annual convention days after the Starr report was released, Pat Robertson brought the hall to its feet with a call to impeach the president: "As landlords of the White House, it's time to tell this occupant his lease has expired!"

This sentiment was shared by many Republicans on Capitol Hill, but their zeal for impeachment lived uncomfortably alongside another reality: The public didn't seem to want it. Poll after poll had been showing this, from the first reports of the Clinton-Lewinsky affair in January, through Clinton's compelled admission in August, to the release of the Starr report and all its lurid details in September.

By the start of October, a survey found that 70 percent of Americans believed that Clinton had lied under oath about the affair, that he'd committed a crime; yet only 36 percent wanted him impeached because of it. Most just wanted Congress to drop the matter altogether.

Republican leaders faced a quandary. All year, they'd been expecting a strong November. If nothing else, history was on their side — the opposition party hadn't lost seats in a midterm in generations. As the scandal initially unfolded, Speaker Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., even forecast that his party would add 10 to 40 seats to its majority. But the polls weren't budging. The GOP base was demanding a course of action that the rest of the country was apparently against.

Republican leaders opted to side with the base and introduced a resolution to launch a formal impeachment inquiry against Clinton. The actual hearings, Republicans insisted, wouldn't be held until after the election, but they wanted to get the House on the record before it.

"The question asks itself," Rep. Henry Hyde, R-Ill., the Judiciary Committee chairman, said during an Oct. 8 floor debate. "Shall we look further, or shall we look away?"

Democrats rallied in opposition. The Republican majority, declared Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., was exhibiting a "shameless and reckless disregard for the Constitution."

The final vote was 258-176 to go forward with the impeachment probe. Every Republican supported it, with 31 Democrats joining them. But Democratic leadership and the vast majority of the party's rank-and-file voted against.

Strategically, Democrats wanted to portray the impeachment push as a partisan crusade led by Republicans who were hell-bent on taking down the president. Just before the vote, Rep. Charlie Rangel, D-N.Y., looked out at the Republican side of the chamber and warned: "The voters will be judging you on November the 3rd."

By planting the impeachment flag, Republicans believed they were motivating their core voters to turn out on Election Day. They were also calculating that Democrats, demoralized by their president's reproachful behavior, would end up sitting the election out.

Instead, the House GOP's embrace of impeachment activated those Democratic voters, who showed up on Election Day in numbers large enough to defy history. Not since 1822 had a White House party gained ground in the sixth year of a presidency; but on Nov. 3, 1998, Bill Clinton's Democratic Party picked up five seats in the House.

Stunned Republicans looked for answers, and within days Gingrich was overthrown as speaker.

Clinton, meanwhile, could breathe a sigh of relief. Republicans would still press forward with impeachment, but to remove the president from office, they would need some Democrats to buy in. The result of the midterms all but guaranteed that Clinton would receive his party's top-to-bottom loyalty. When, weeks later, the House and Senate finally voted on impeachment and removal, the only cracks ended up being on the Republican side, and Clinton was saved.

It's no coincidence that the top three Democratic leaders in the House today — Nancy Pelosi, Steny Hoyer and Jim Clyburn — were all there in 1998 and are all quiet on the impeachment front now.

They remember the energizing effect that a push to remove their party's president had on their voters, and they all fear giving Trump's party that kind of motivation this fall. The same goes for the top Democrat in the Senate, Chuck Schumer, then a congressman who took advantage of the impeachment backlash of '98 to defeat three-term GOP Sen. Al D'Amato in a New York Senate race for the ages.

The Clinton and Trump situations aren't analogous in every way.

There is, obviously, no equivalent of the Starr report, at least not yet, and even if there was, Democrats could only agitate for impeachment — they don't currently have the votes in the House to push it through. Trump would also enter any impeachment showdown with far less popularity than Clinton had, but in our tribalized politics, the name of the game isn't necessarily having the larger army, but the more motivated one.

In that sense, Democratic leaders are content to do what the Republicans of 1998 did not do: They're playing it safe.

Steve Kornacki’s upcoming book, "The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political Tribalism," can be ordered here.