WASHINGTON — On the surface, the American political system looks fairly steady, with two well-known behemoths, the Democratic and Republican parties, fighting for control.

But those two parties have changed a lot in recent years and those changes have remade American politics.

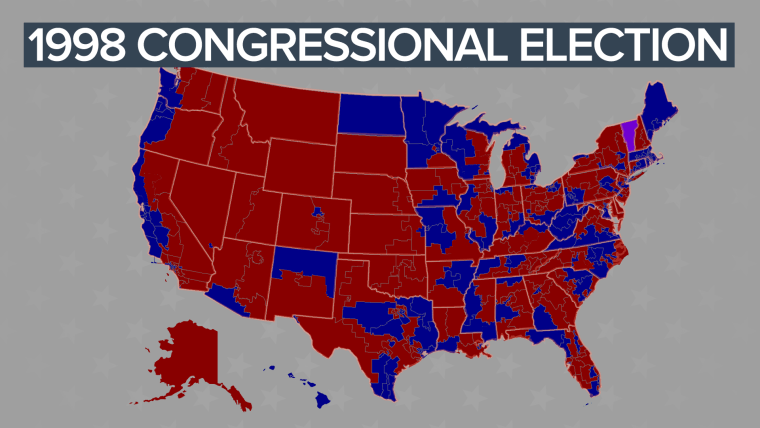

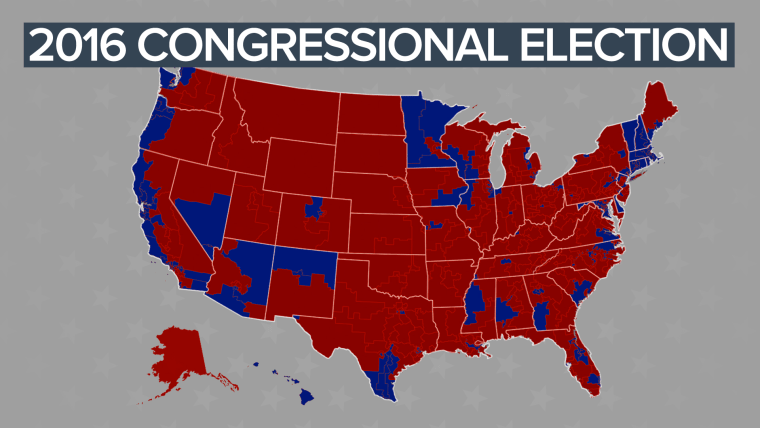

Philosophically and geographically the Democrats and Republicans look very different than they did in the 1990s. You can see it by looking at maps for the House of Representatives from the 2016 and 1998 elections (the last Congress of the 20th Century).

Those maps reveal some big differences. Republicans are in retreat in states like California, Connecticut and Maryland. Democrats have seen their numbers dwindle in states such as Arkansas, Texas and West Virginia.

Some of those moves have to do with which party controlled redistricting in the state, while other changes are due to population shifts, but the numbers fit with the larger demographic trends in the two parties. The Democrats have increasingly become home to better-educated whites and minority voters, while Republicans have seen their support grow among blue-collar whites.

Beyond simple demographics, however, those shifts have had impacts in how business gets done in Washington because they have altered the kinds of people that serve in Congress.

The last 20 years have witnessed a change in the political archetypes in the Capitol. Gone for the most part are moderate Rockefeller Republicans of the Northeast and the conservative “blue dog” Democrats of the South. Replacing them are more-consistently liberal urban Democrats and staunchly conservative southern GOPers.

Consider a few examples.

In Connecticut, moderate Republican Chris Shays represented the 4th congressional district for more than 20 years, surviving both Democratic and Republican presidents and congressional redistricting. As recently as 2002 he won re-election with 64 percent of the vote, but in 2008 the seat swung to Democrat Jim Himes in a close race. In 2016, Himes won re-election with 60 percent of the vote.

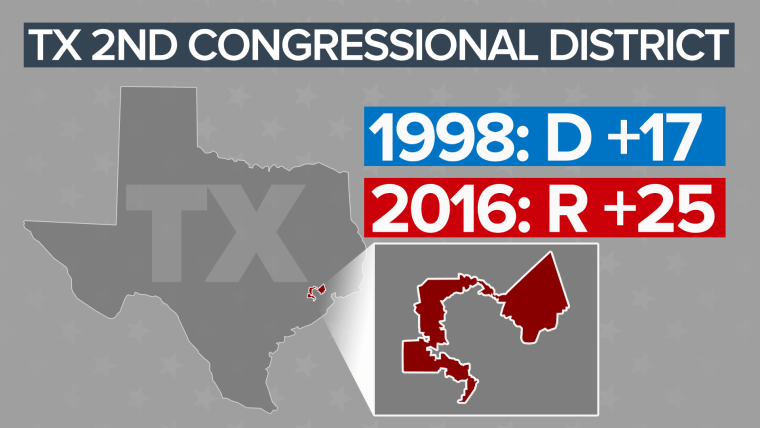

In Texas, the 2nd district was held by Democrat Charlie Wilson, a defense hawk and gun enthusiast, for 12 terms. He was succeeded by moderate Democrat Jim Turner. In 2002, Turner won re-election with 61 percent of the vote. The seat flipped in 2004 and has since been held by Republican Ted Poe, a conservative former judge who won re-election in 2016 with 61 percent of the vote.

In both cases, the losses of these seats — by the GOP in Connecticut and the Democrats in Texas — weren't about losing people, but about weakening the ideological diversity within the parties. And as the parties on Capitol Hill become more philosophically homogeneous internally, it gets harder to find common ground between them.

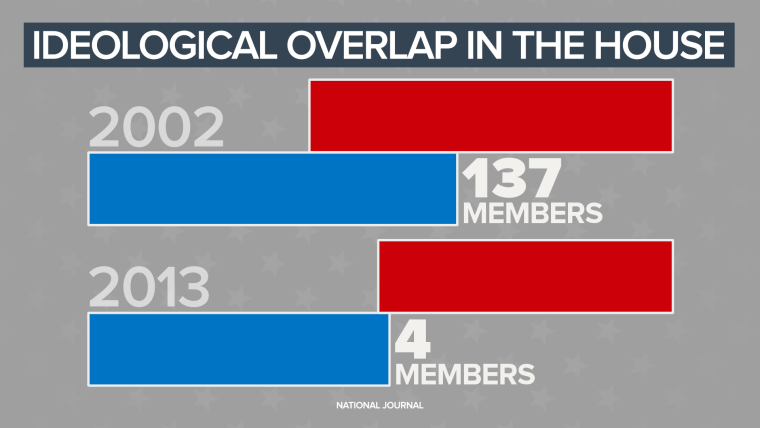

Those problems are clear in the data.

National Journal regularly analyzes the partisan split in Congress by looking at members who have voting records somewhere in between the most conservative Democrat and the most liberal Republican. It’s a way of defining the political center. In 2002, 137 members fell into that overlapping group. In 2013, that number was down to four.

With numbers like those it’s not a surprise that members of Congress have a hard time finding common ground on much of anything. The changes in the two parties over the last 20 years — ideological and geographic — have simply pushed them farther apart, literally.

Does this mean Congress is stuck in a loop of endlessly growing partisanship? Maybe not.

After years of stasis, the Democratic and Republican coalitions look like they are fragmenting. Donald Trump’s candidacy and presidency have shaken the traditional fault lines of the American political scene and accelerated what many analysts see as a coming realignment. (Note the Republican struggles to reform health care, even with majorities in both houses of Congress and the White House.

But for now the two major brands of American politics, the Democrats and Republicans, have formed into tight ideological groups and walked themselves into their respective corners. Without a major shakeup, coming to the middle won’t be easy.