It would start with a proclamation from the Senate's sergeant-at-arms: "All persons are commanded to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment, while the House of Representatives is exhibiting to the Senate of the United States articles of impeachment against Donald John Trump."

It would end with senators voting on whether the president should be found guilty of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

Much of what happens in between would be decided by a simple majority of senators, all of whom would effectively be barred from speaking during the bulk of the proceedings.

If, as expected, the House passes articles of impeachment this week, lawmakers won't have much history to rely on as a guide — the proceeding would be just the third impeachment trial of a president in U.S. history. Andrew Johnson was acquitted in 1868, and Bill Clinton was acquitted in 1999. (Richard Nixon resigned in 1974 after the Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment but before the full House voted on them.)

Here's what to expect at a Senate impeachment trial of the president.

Who are the prosecutors?

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., would name an unspecified number of House members as case managers who would, in effect, act as prosecutors at the trial. Those names have yet to be revealed, but Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff, D-Calif., and Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nadler, D-N.Y., are expected to make the cut. Johnson's trial had seven case managers, while Clinton's had 13. One of the Clinton case managers was Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., a top ally of the president, who was then in the House.

Who are the defense lawyers?

It's not yet clear who would defend the president at the trial, but his team is expected to be led by White House counsel Pat Cipollone, who's been strategizing with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and other Senate Republicans. A source told NBC News that there have been discussions about adding Alan Dershowitz to the president's legal team. He would be a controversial addition — his previous clients include O.J. Simpson and Jeffrey Epstein.

Who presides over the trial?

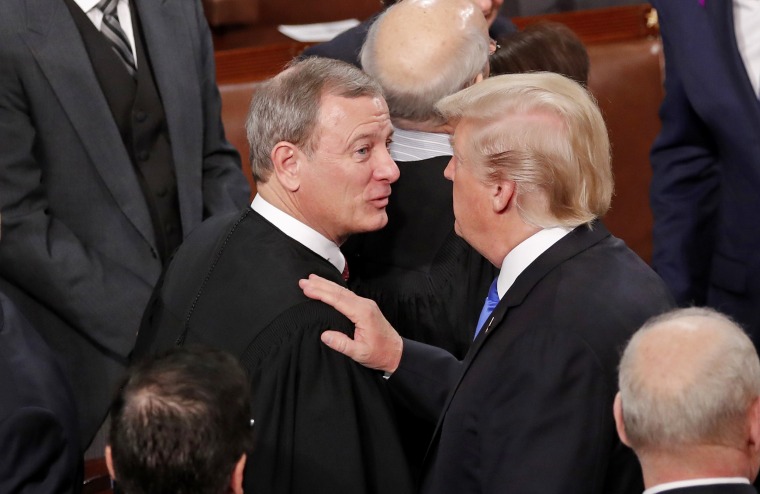

John Roberts, the chief justice of the United States, would preside over the trial, but his role would be more limited than that of a judge in a traditional trial. He would rule on evidentiary questions — or he could pass that role off to the Senate and have it vote on those questions.

If there's a 50-50 split, Roberts could act as a tiebreaking vote. That's a role typically played in the Senate by the vice president, who is the president of the Senate, but the vice president can't do that in a presidential impeachment trial because of conflict of interest issues. (The judge during Johnson's trial, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, cast two tiebreaking votes.)

The Senate could also override Roberts' decisions with a majority vote.

Who are the jurors?

The entire Senate would be the jury, but with some differences from a typical civil or criminal jury.

In addition to being able to vote on procedures and evidence, senators could submit questions and objections to the chief judge. And while judges strive to pick unbiased civil and criminal juries, that wouldn't be the case here. The Senate has 53 Republicans, 45 Democrats and 2 independents. Four of those Democrats, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, Cory Booker of New Jersey and Michael Bennet of Colorado, are running for president, as is one of the independents, Bernie Sanders of Vermont. McConnell, meanwhile, told Fox News' Sean Hannity on Thursday that he's working in "total coordination" with the White House.

"Exactly how we go forward I'm going to coordinate with the president's lawyers, so there won't be any difference between us on how to do this," McConnell said. "My hope is there won't be a single Republican who votes for either of these articles of impeachment."

How do proceedings begin?

The House would inform the Senate of its named impeachment managers, and the Senate would tell the House that it is "ready to receive the managers for the purpose of exhibiting such articles of impeachment."

The managers would head to the Senate floor, where they would be introduced by the sergeant-at-arms. The sergeant-at-arms would then tell the Senate "to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment," while the managers introduce the two articles of impeachment.

The next day, at 1 p.m. ET, Senate rules say, they would "proceed to the consideration of such articles and shall continue in session from day to day (Sundays excepted) after the trial shall commence (unless otherwise ordered by the Senate) until final judgment shall be rendered."

The Senate would need to establish rules of procedure — McConnell has suggested that he'd use the Clinton procedures as a template — and the president's attorneys could file paperwork outlining his defense.

Roberts would be sworn in, the senators would be sworn in and then the six-day a week trial would officially be underway.

What happens in the trial?

The House managers would make their opening statements, followed by the attorneys for the president. In the Clinton trial, each side had a total of 24 hours to make its presentations. When they were done, senators were able to question the two sides for 16 hours. The senators submitted their questions in writing to Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who read them aloud.

If the Senate follows the Clinton procedures, senators could call for a vote to dismiss the case after the questioning. If they don't have the 51 votes to do so, they could then vote to subpoena witnesses and hear additional evidence.

Who will the witnesses be?

Democrats would love to call witnesses who were blocked from testifying in the House, such as acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former national security adviser John Bolton. Trump said Friday that he wants the person who reported his call with Ukraine's president to take the stand. "I'd like to see the whistleblower, who's a fraud, having the whistleblower called to testify in the Senate trial," Trump told reporters at the White House.

Odds are, however, that there wouldn't be any witnesses at all. While Trump has said he wants witnesses as part of a robust defense, McConnell and Graham have suggested that they might rely on the evidence that was presented before the House.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

"Here's what I think is best for the country, that we listen to the House's case based on the evidence they used to impeach if they do, that we not build upon that record. We let the president give his side of the story of why it's not impeachable, then I think we should vote and end it," Graham told reporters on Wednesday.

There is precedent for not calling live witnesses. While Johnson's trial featured direct testimony from 25 prosecution and 16 defense witnesses, Clinton's trial had none. Instead, three witnesses were deposed on video, and snippets of their testimony were played during the trial.

If no witnesses were called, the case would then go to closing arguments. The Senate would deliberate behind closed doors before voting on each article in open session.

How many votes are needed to convict?

It takes a super-majority — 67 votes — to convict. Anything else leads to acquittal. Neither verdict could be appealed to a court.

What would happen if the Senate convicted Trump?

He would be immediately removed from office, triggering the 25th Amendment. Vice President Mike Pence would become president.

That would create a vacancy in the office of vice president, so Pence would nominate someone to succeed him, who would become vice president upon confirmation by both houses of Congress.