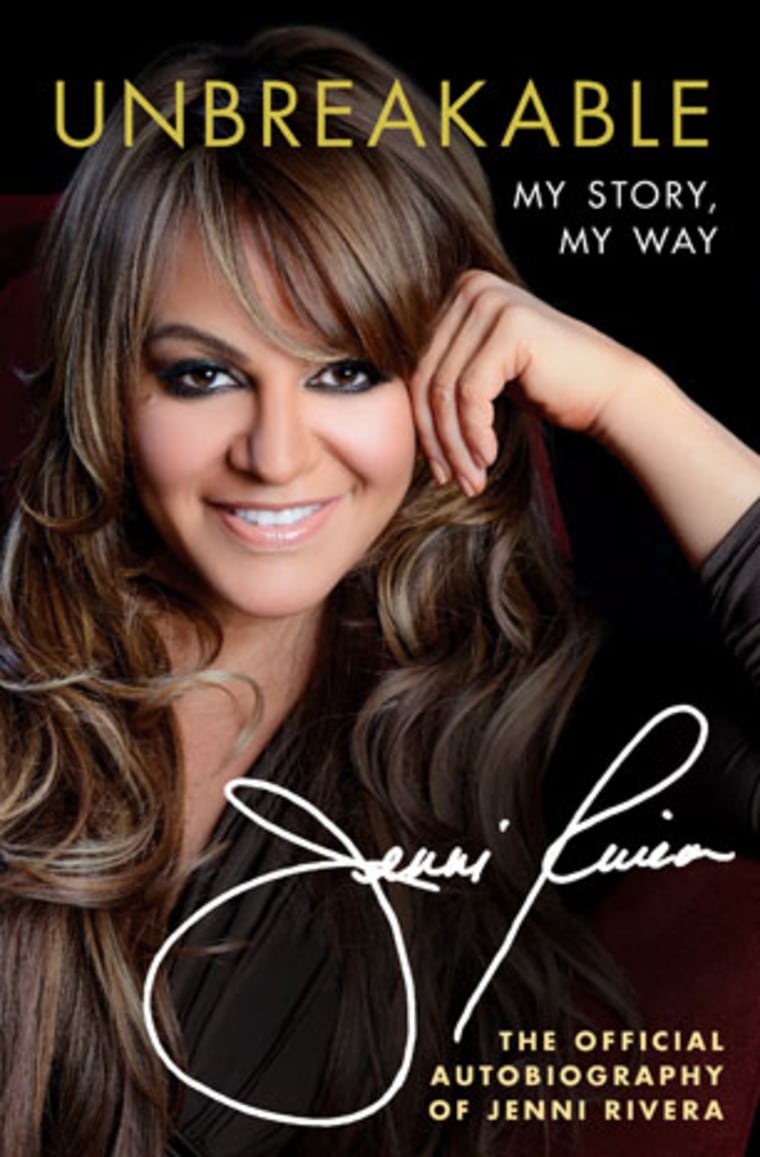

Mexican American singing sensation Jenni River died tragically in a plane crash on December 9, 2012, leaving behind a grieving nation of fans. In "Unbreakable, " her posthumously published memoir, Rivera looks back on her struggle and remarkable accomplishments. Here's an excerpt.

The Rivera Way

Que no hay que llegar primero

Pero hay que saber llegar.

(You don’t have to arrive first

but to know how to arrive.)

—from “El Rey”

My father, Pedro Rivera, first came to the United States in the sixties. He left my mother, Rosa, and my two brothers, Pilly (Pedro) and Gus (Gustavo), behind in Sonora, Mexico, with the promise to return for them when he had enough money. He headed to California in hopes that he would find work. He crossed the border illegally with three other men in a dangerous and risky passage. When they finally made it to San Diego, the other men wanted to sleep, but my dad is one of those people who always has to keep working. If there is one thing he doesn’t know how to do, it’s rest.

Dad left his three companions sleeping in the shade and walked to the nearest gas station. He asked the man at the counter if there was somewhere he could work. The man told him to go to Fresno; that was where the work was at the time. “Great,” my dad said. “How do I get there?” The man told him to take the Greyhound bus. The problem was, by the time my father made it to San Diego he had only sixty cents in his pocket, which was not enough to pay the Greyhound fare. When he told the man that he had no money, the man paid for his bus ticket and gave him an extra $20. To this day, my dad cries when he remembers that moment. It changed his life.

So my father followed the man’s advice and went to Fresno, where he started to pursue the American dream. He worked in the fields, picking grapes and strawberries. For the first few months, he lived with friends he had met there. He finally saved enough to rent a little apartment and then return to Mexico to get my mother and brothers.

But while my parents were in Mexico getting ready to leave for the United States, my mother became pregnant with me. She was twenty years old and terrified. She was leaving for this new country where she didn’t speak the language, they didn’t have money, and she already had two young children. The last thing she wanted or needed was another mouth to feed. So she tried, in every way possible, to abort me. She threw herself into burning-hot water. She moved the refrigerator and other heavy furniture, hoping that the pressure and strain would terminate the pregnancy. She drank teas and other home remedies that friends told her about. Nothing worked. Many years later, when I was sitting at her kitchen table and telling her I was about to give up on life, she told me this story. She said that back then she knew that I was a fighter, that I would always be a fighter.

I was born on July 2, 1969, in the UCLA hospital, the first Rivera born on US soil. The hospital was new and they had a program through which it only cost $84 to have a baby. Thank God, since my parents did not have health insurance. When I was growing up, my father would always say I was their cheapest baby. They named me Dolores, after my maternal grandmother. My middle name was going to be Juana, after my paternal grandmother. Dolores Juana. Can you imagine? Ugliest name ever! My mother had the good sense to say, “We can’t do this to her. Isn’t there an English version of Juana we can use? Or what about using your cousin’s name, Janney?” My father caved and I was christened Dolores Janney. Still not exactly the most beautiful name you’ve ever heard. I never let my parents off the hook for that one. “I was a baby! How do you give a child a grown woman’s name?” I would say. I never went by the name Dolores (though if my brothers and sister wanted to piss me off, that’s what they would call me, or Lola). As a child, I was always Janney or Chay.

I was a fair-skinned, redheaded baby. My parents said that when they brought me home my older brothers, who were five and three, instantly fell in love with me. Pilly and Gus were instructed to protect me and care for me. I was “the queen of the house” and “la Reina de Long Beach,” as my father said. If anything bad ever happened to me, it was on them. So they treated me as if I were another little boy. Since they had to protect me, they wanted to make sure I was tough enough to defend myself.

Financially, things were not good during those first few years. My parents moved us from Culver City to Carson to Wilmington and then to Long Beach. We were constantly on the move because we were always being evicted. My mother told my father that she would not have another baby until she had her own house. That’s when they bought the small two-bedroom on Gale Avenue near Hill Street on Long Beach’s West Side. The area was known for gang warfare, but it was the first place where the Riveras finally had a plot of American land to call their own. It was home.

I was almost two when we moved into that house, and my mother immediately became pregnant with her fourth child. Soon after she found out that she was pregnant, she got the news that her father was dying in Mexico. She couldn’t go back to see him because there was no money, and because if she crossed over the border again, she might not have been able to come back. One of the dilemmas of pursuing the American dream is that you sacrifice being able to ever see the friends and family you left behind. Back then I never realized how hard it must have been for my mother to be living in this new country, barely getting by financially, with three young children and another on the way. But how could I have known? My mother never let on that anything was wrong. She kept her chin up and acted as if everything were just fine, so we did too.

Mommy would have me rub her belly to get me acquainted with the little girl that was on the way. She wanted to have a baby girl so I could have a sister and we could grow up together and be lifelong friends, just like her and her sisters. It would be perfect. Two boys and two girls. But my mother’s wishes didn’t come true.

From "Unbreakable:My Story, My Way" by JenniRivera. Copyright © 2013. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books.