Scientists have already used 3-D printing technology to help produce human body parts like an ear, but what about a full-blown organ like a liver, kidney or heart? Companies like the San Diego-based startup Organovo broke new ground in this field in 2013. Having successfully printed human liver tissue, the company is now planning a product launch (of sorts) for 2014 in the form of 3-D printed liver models that can be used by other pharmaceutical companies for toxicology testing.

Don't think "Frankenstein" quite yet, though. We're far from — and may never get to — the point where somebody will be able to just press "Print" from a home computer and get a brand-new liver. Scientists won't be growing human hearts and lungs in large glass tubes anytime soon. Speaking in an interview with NBC News, Keith Murphy, chairman and CEO at Organovo, emphasized that what his company is making is "tissue for research," not a "liver for immediate transplant."

But even then, the work still offers an incredible potential for improvement from older models of research and development, Stuart Williams, scientific director of the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute in Louisville, Ky., who has worked with Organovo in the past, told NBC News.

"We're getting very good at printing out the parts for the aircraft carrier, but not the whole carrier yet," Williams said. "So for a near-term application, what this allows us to do is print out the cells that are in the liver and use those to test out the safety of certain drugs, for instance."

Williams said that Organovo's real achievement in this regard isn't necessarily a result of new technology. Using 3-D printers to produce organic material with human cells has been a part of the biomedical industry since the late '90s, he explained. But what Organovo was able to do better than anybody else was make what Williams called a superior "recipe" that kept the liver tissue intact and performing its essential functions for an extended time.

Jordan Miller, a professor of bioengineering at Rice University, agreed with Williams, telling NBC News that, once they are extracted, "liver cells are one of the most fragile types of cells in the human body."

"It's been a huge area of interest for decades," Miller said. "The ability to stabilize them long enough that you can print them is very exciting."

Placed in a standard Petri-dish culture, Organovo's Murphy explained, liver cells will "stop functioning like the liver after 48 hours." Using its 3-D printing technique, Organovo was able to get its liver samples to last for 40 days. This allows researchers to measure subtler and longer-term effects of drugs on the liver.

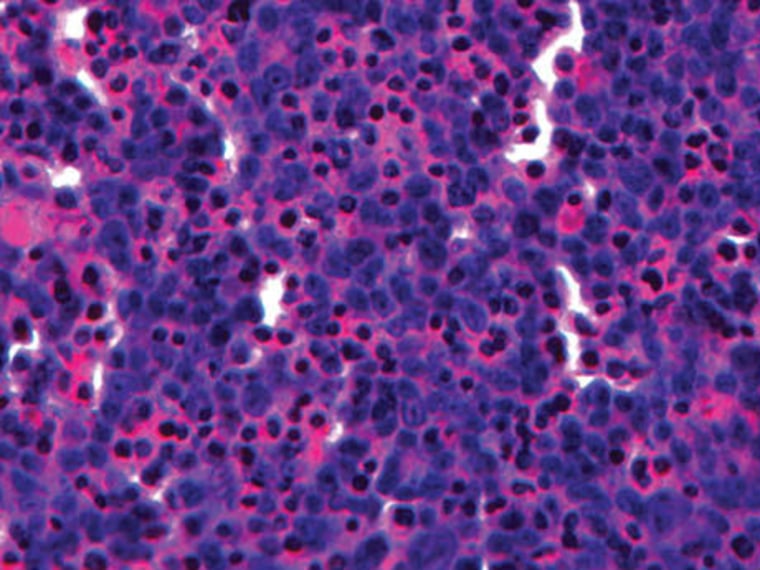

Improvements in the technology have also allowed them to make the tissue as thick as one millimeter. While that might not sound like much, it goes a long way toward replicating the actual physical structure of the organ, down to the level of its microvascular architecture. So rather than simply analyzing a cluster of isolated cells, scientists can see these mini-organs (Williams referred to them as "tissue mimics") acting as a real liver would: producing essential proteins, cholesterol and bile — not to mention clearing the blood of toxic materials.

It's hard to predict where researchers will take this kind of work in the coming months and years, but Miller told NBC News that 3-D printing techniques like Organovo's give the entire field something it's always needed more of: data.

"What we need in the biomedical industry is a lot of data," Miller said. "We need to be able to produce many experiments a number of times to get enough information to make solid conclusions. This extremely reproducible fabricated tissue gives us the architecture to actually produce that."

Organovo won't be the only company trying to build this new architecture, however. Earlier this month, the Methusela Foundation, a Springfield, Va.-based nonprofit that offers funding for research into regenerative medicine, announced that it would issue a $1 million prize to the first organization that produces a fully functioning human liver.

"They're not alone," Williams said of Organovo. "There is a real arms race for printing all these organs."

Yannick LeJacq is a contributing writer for NBC News who has also covered technology and games for Kill Screen, The Wall Street Journal and The Atlantic. You can follow him on Twitter at @YannickLeJacq and reach him by email at: Yannick.LeJacq@nbcuni.com.