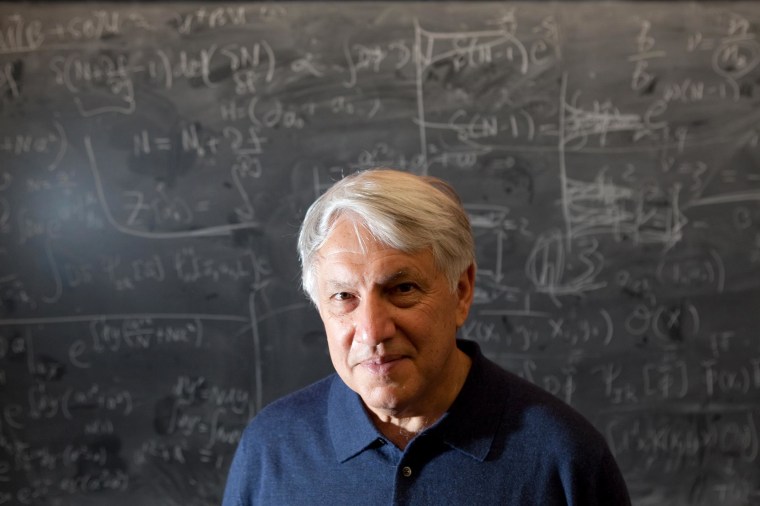

When a video crew recorded Stanford University physicist Andrei Linde's jaw-dropping reaction to the news that hush-hush findings confirmed more than three decades of his theorizing, reality TV couldn't have planned it better.

In just one day, the video has attracted 1.2 million views on YouTube and enough kudos to fill a particle collider.

But what made the moment even sweeter is that it wasn't really all that planned. In fact, Stanford News Service's Bjorn Carey had no idea what would happen when he walked up to Linde's door with videographer Kurt Hickman and the bearer of the glad scientific tidings, experimental physicist Chao-Lin Kuo.

"We knew it'd be great," Carey told NBC News. "We just didn't know whether we'd be able to use it."

The "Candid Camera" moment was sparked by data from detectors at the South Pole. The readings from the BICEP2 experiment pointed to the existence of primordial gravitational waves, thrown off by a gigantic burst of inflation during the first instant of the Big Bang.

Theorist was kept in the dark

If the findings hold up, they would serve as confirmation of inflationary Big Bang theory. Along with MIT physicist Alan Guth, Linde is considered one of the pioneers of that theory — but he was kept in the dark about BICEP2's progress.

About two weeks ago, Kuo, a Stanford researcher who is one of the leaders of the BICEP2 collaboration, told Carey about the big news to come — and Carey instantly suggested letting Linde know in advance. Kuo thought he'd head over to Linde's house with a bottle of champagne. Then Carey asked if he and Hickman could tag along.

"It took a little convincing to get Chao-Lin to do it," Carey recalled, but after a couple of fits and starts, the team arrived at Linde's doorstep.

As you can see in the video, Kuo's knock was answered by Renata Kallosh, Linde's wife and a physicist specializing in string theory at Stanford. When Kuo reported the bottom line for BICEP2's observations, Kallosh gave him a hug, but Linde was so gobsmacked that he needed to hear the numbers two more times.

The video skips over the detailed explanations and the gazing into Kuo's laptop. Instead, it cuts right to the champagne toasts and Linde's reflections on the revelations.

"We did not expect anybody," he said as the camera rolled. "Renata tells [me], 'It's probably some kind of delivery. Did you order anything?' Yeah, I ordered it 30 years ago. Finally it arrived!"

Case closed? Not yet

Linde acknowledged that there were times when he wondered whether he was on the right track: "I always live with this feeling. 'What if I am tricked? What if I believe in this just because it is beautiful?' ... So this is really helpful to have events like that. Really, really helpful. Thank you so much for doing it."

It goes without saying that Linde and Kallosh gave their OK to make the video public. Carey said he and the other messengers were even offered celebratory chocolates.

On Monday, Linde (and many other physicists) said the BICEP2 results served as a "smoking gun" in the investigation of cosmic origins. But the case isn't closed yet. Some physicists say the readings are so different from what they expected that they're waiting for further confirmation, in the form of data expected within the next two years from the European Space Agency's Planck mission.

"Considerable caution is advised until the BICEP2 measurement has been verified by some other experiment," theoretical physicist Matt Strassler, a visiting scholar at Harvard, said on his blog. "Moreover, even if the measurement is correct, one should not assume that the interpretation in terms of gravitational waves and inflation is correct; this requires more study and further confirmation."

High stakes for physics (and gambling physicists)

If the BICEP2 results and their interpretation hold up, it could lead to dramatic new clues to the nature of gravity and dark energy, Strassler said. The "wow" factor would be at least as high as the hype surrounding the discovery of the Higgs boson, he said. That's why it's so important to verify the BICEP2 team's claims.

As if the future of high-energy physics weren't enough, there are also a couple of bets riding on this. For example, in 2002 Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking bet Neil Turok, director of Canada's Perimeter Institute, that primordial gravitational waves would someday be detected. Now Hawking says it's time for Turok to concede. In response, Turok is saying he won't yield until the Planck results are in.

In 2009, Caltech physicist Sean Carroll bet MIT's Max Tegmark $100 that Planck would fail to find evidence of primordial gravitational waves. Although BICEP2's findings don't technically settle the bet, it's not looking good for Carroll right now.

"I might owe Max Tegmark $100 — at least, if Planck confirms the result," Carroll acknowledged in a blog posting. "I will joyfully pay up."

For more about the making of the Stanford video, check out this report from The Atlantic's Megan Garber.