Methane appears to be bubbling up from more than 500 vents on the Atlantic Ocean floor off the U.S. East Coast, according to a new study in a finding that could have profound long-term implications for the global climate.

While scientists suspected these so-called seeps existed there, until now they lurked undetected. Their discovery suggests similar seeps exist throughout the world's oceans.

The seeps come from gas hydrates, an ice-like combination of water and methane that forms naturally with extreme cold and depth in the ocean. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and gas hydrates are thought to hold up to 10 times as much carbon as the earth's atmosphere.

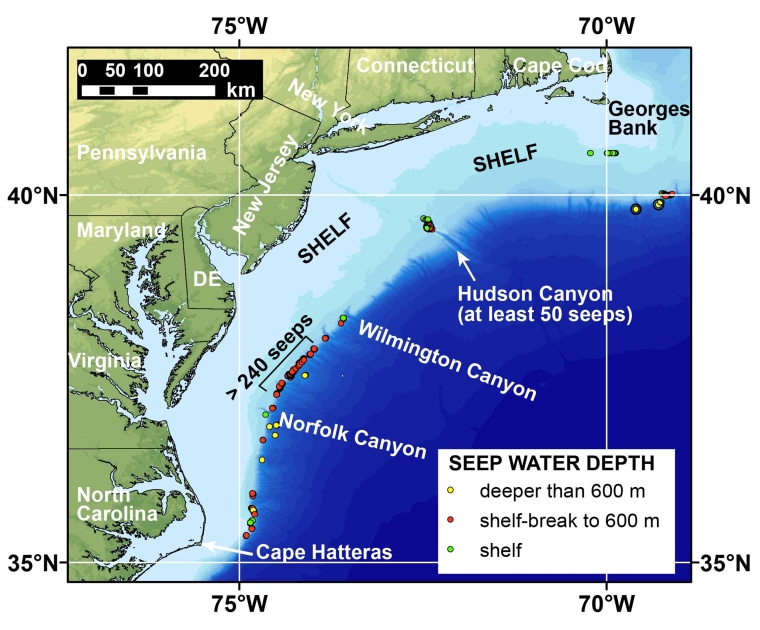

The seeps were discovered in a stretch of ocean waters from Cape Hatteras, N.C., to Georges Bank, Mass. The majority are located at a depth of about 1,640 feet, which is at the upper level of stability for gas hydrate.

"Warming of the ocean waters could cause this ice to melt and release gas," Adam Skarke, a geoscientist at Mississippi State University and the study's lead author, told NBC News. "So there may be some connection here to intermediate ocean warming, though we need to carry out further investigations to confirm if that is the case," he added.

The gas, which hasn't been directly sampled but circumstantial evidence suggests is methane, is being released too deep to make it directly to the atmosphere, noted paper co-author Carolyn Ruppel, chief of the U.S. Geological Survey's Gas Hydrates Project in Woods Hole, Mass.

The majority of the methane can be oxidized to carbon dioxide, which increases ocean acidity and reduces oxygen levels. Some is turned into carbonate rock and a tiny bit may escape to the atmosphere as methane or carbon dioxide.

"There is a sense that the upper ocean is absorbing a lot of the heat from global warming and a lot of these seeps are sitting right at the water depth where they are going to be affected by that warming," Ruppel told NBC News, adding that "those warmer waters impinging on the upper slope could be triggering maybe a more active phase of methane emissions."

Whether or not that is actually happening, for now, is unknown, noted Gerald Dickens, an earth scientist at Rice University in Houston, Texas, who has studied gas hydrates for more than 20 years and long suspected seeps existed in continental shelf sediments. He was not a part of this study.

"Certainly, the first question is, is this normal," he told NBC News. "In other words, is this just a steady state and we just haven't looked at it?"

'Prolonged seepage'

Skarke, Ruppel and colleagues used sonar instruments to identify the seeps and subsequently revisited a few of them with a remotely operated vehicle. Images of the seafloor indicate the presence of carbonate rock, which forms over timescales measured in centuries via a series of chemical reactions starting with methane and sulfate.

"The fact that it is there in the quantities that it is and it is exposed suggests that indeed the processes at these locations have been going on, in a very general sense, on the order of at least 1,000 years," Skarke said. While more seeps need to be visited to see if there is similar evidence elsewhere, "the ones we visited suggest a very prolonged seepage," he added.

"Direct transfer of even a small fraction of this methane to the atmosphere would have catastrophic effects on Earth's climate."

The researchers have yet to determine whether the newly detected seepage represents a more active phase where "there is more gas leaking and less is going into carbonate," Dickens explained. "One would predict that as you start warming the ocean, the output has to increase," he added.

The second question that begs to be answered concerns how widespread the phenomenon is, he continued.

While researchers have long suspected gas hydrates are ubiquitous in the world's ocean, until now few seeps were known outside of the Arctic. The new research confirms the hunch and suggests that "tens of thousands of seeps could be discoverable," Skarke, Ruppel and colleagues write in their study published Sunday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Methane-climate connection

Previous studies have estimated that gas hydrates may hold as much as 10 times more carbon than the atmosphere, John Kessler, a chemical oceanographer at the University of Rochester in New York, noted in a perspective article that accompanies the new study.

"Direct transfer of even a small fraction of this methane to the atmosphere would have catastrophic effects on Earth's climate, a process that has been proposed as both an initial driver of and positive feedback to climate change," he wrote. The new discovery, he added, points to "one of the best locations to critically evaluate the interplay of changing climate and oceanic methane."

Within the next 100 years or so, any major impact on the global climate from methane, which is about 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide, will come from methane emitted from tropical wetlands and human activities, not the oceans, noted David Archer, who studies the global carbon cycle and global climate at the University of Chicago.

"In the timescale of centuries to hundreds of thousands of years, (gas hydrate) is clearly a significant amplifier," he told NBC News. "But in terms of the climate of just the coming century, the actual forcing of climate from the rise in atmospheric methane due to this, I think, will be small."