SAN JOSE, Calif. — Climate experts have seen the future of America's breadbasket — and from their perspective, it doesn't look pretty.

"I don't want to be a wheat farmer in Kansas in the future," said Harold Brooks, a senior scientist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma.

Brooks isn't a wheat farmer. He's a researcher who has analyzed how climate change could affect the weather in America's midsection, based on historical data and computer modeling. Last year, he and his colleagues found that tornado patterns are becoming more variable — with severe storms coming in bunches or not at all.

There's more variability in the long-term weather outlook as well, Brooks said this month in San Jose during the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Some climate models suggest there'll be more storms, while others suggest there'll be more drought.

Either scenario is bad for the farmers. "I lose all my crop because it gets hailed on, or it burns up," Brooks said.

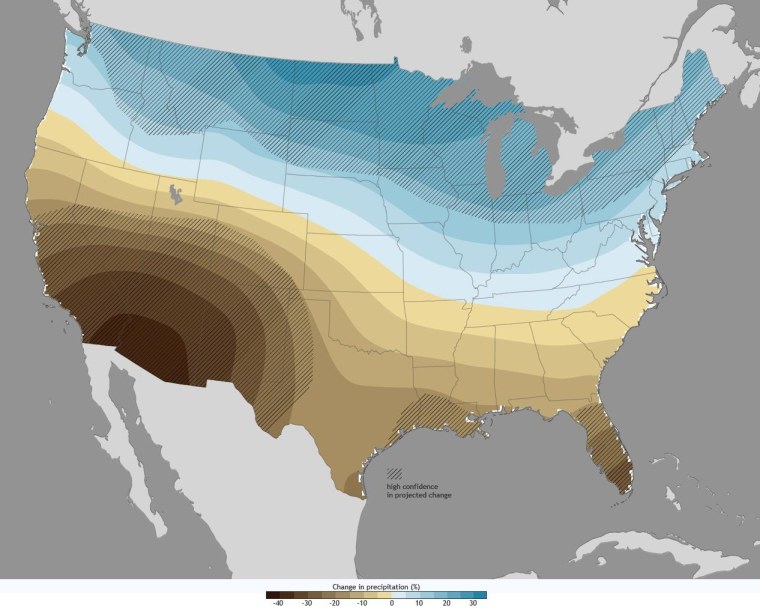

In a warmer world, the threat of drought is drawing more attention. "If I look at the future, and I say, 'What's the biggest threat to food security in the future,' at least from a Midwest perspective, it is more intense, major droughts," said Kenneth Kunkel, senior scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites.

More heat waves

It's no surprise that drought is a big part of the climate forecast, but Brooks, Kunkel and other experts are now working out how a rise in global mean temperatures are likely to translate into changed weather conditions for key areas, including America's wheat belt and corn belt.

Last year, for example, researchers matched up their computer models with weather data in an attempt to determine the contribution of human-caused climate change to extreme weather events ranging from western Europe's heat wave to California's mega-drought. Their verdict: Greenhouse-gas emissions played a substantial role in Europe's misery, but not so much in California.

Looking ahead, the models predict that today's heat-wave conditions will become the norm in Europe. "By the end of the century ... this event will seem cold," said Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at Berkeley Lab who helped write the latest U.N. climate report.

Shifting grain belt

The outlook suggests that the most suited region for U.S. crop production will shift northward as global temperatures increase. Although it's dangerous to read too much into one year's statistics, North Dakota surpassed Kansas as the nation's top wheat-producing state last year, due primarily to Kansas droughts.

Theoretically, reduced production along the southern edge of the country's grain-producing regions should be offset by increased production along the northern edge. The Corn Belt (and Soybean Belt) is already pushing up past the Canadian border, and Canada's wheat-producing zone is creeping farther north. But in reality, the shift is still likely to produce a net loss in crop production, said Jerry Hatfield, director of the USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment.

"We're going to consume soil resources, because the urban population that we're going to build up is going to consume more land as well," he said. "We'll lose other parts of the land because of excessive erosion and degradation that occurs. As we move agriculture north, we're going to be putting it in areas that don't have the same water-holding capacity, nutrient-holding capacity."

Hatfield said the world's increasing population, plus the rise in per capita consumption that comes with economic development, will add to the pressure. Between the year 2000 and 2050, "we basically have to produce the same amount of food as we've produced in the last 500 years," he said.

Can we adapt?

The experts said heading off a food crisis will require changes in every aspect of production and consumption. "Adaptation strategies should be under way," Wehner said. "Denying this, I think, is a disservice to the public."

Among the strategies: developing new crop strains that produce bigger yields; reducing waste at every step in the food production chain; and eating less meat, to cut down on the huge amounts of grain that are consumed by livestock.

Will we be able to feed the world in 2050? "I'd say we could, but I would bet against it," said Paul Ehrlich, president of the Center for Conservation Biology at Stanford University. The longtime critic of overpopulation and overconsumption noted that little has been done to counter negative trends in food security, even though they've been known about for decades.

Ehrlich said climate shifts could make things worse, and fast.

"If we had a thousand years to solve this, I'd be very relaxed," he said. "But we may have 10 or 20. That's a different story."