The same crops that have fed a rapidly expanding global population over the last 50 years may pose problems for the global food chain as pests and limited diets spread, according to a new study.

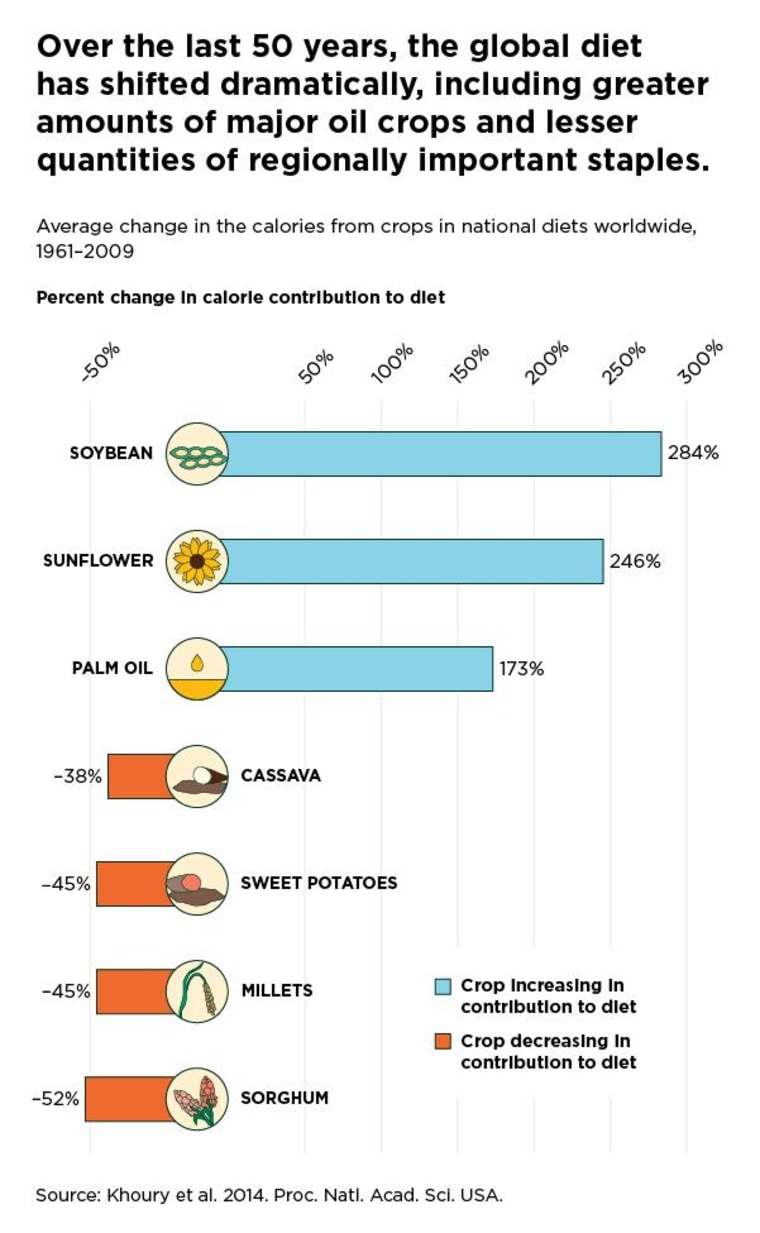

Crops such as wheat, corn, potato, and soybean, as well as meat and dairy products make up a bulk of the world's diet today. Meanwhile, once regionally important crops such as millet, sorghum and yams are losing ground, explained Colin Khoury, a visiting research scientist at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture in Cali, Colombia, and the study's lead author.

"It is not all bad, but there are some very significant implications on both the agricultural side and on the nutritional side," he told NBC News.

Sameness can make food supplies vulnerable. A single crop pest, for example, could lay waste to millions of acres of wheat in a single growing season and send food prices soaring around the world. Meanwhile, diets concentrated on a few crops may accelerate the worldwide rise in obesity, heart disease and diabetes, which are strongly affected by dietary change and are major health problems, according to the study.

Rosy picture in the data

The raw data behind the study, which was published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paint a rosy picture of diets getting richer around the world as a wider range of crops spread into the global marketplace, according to Kenneth Cassman, an agronomist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, who was not involved in the study.

"And so ultimately, the question becomes how diverse is enough."

He cautioned, however, that similarity in the global food system is not all bad.

"Another way to look at that is with limited land and water, there are certain crops that really do a better job in terms of being efficient at converting land and water and other resources like energy and fertilizers into edible products," he told NBC News. "And so ultimately, the question becomes how diverse is enough."

Khoury acknowledged the paradox in the data: there is growing diversity in national diets and more people around the world are being fed, but there is less diversity in crops grown globally. The homogenizing trend, he said, reflects rising wealth, liberalized international trade, and urbanization — factors that are expected to accelerate in the future.

"What that means is more access to processed foods through restaurants, fast food, and supermarkets; less time spent cooking or having a garden or collecting food from the wild," he said.

Breeding in nutrition, diversity

If the world is going to increasingly rely on a few handfuls of major, global crops for the bulk of its food supply, as the data in the paper shows, then breeders must take extra care to boost the levels of nutrients important for human health, such as vitamin A, zinc, and iron in those crops. Doing so can be done through traditional breeding, but genetic engineering could also contribute, said Khoury.

"Examples like the Irish potato famine [and] the southern corn leaf blight in the ’70s in the United States have shown that if you have one variety, pests will find it and make trouble."

As the menu of crops grown around the world continues to narrow, he added, the need for greater diversity within those crops will rise.

"Examples like the Irish potato famine [and] the southern corn leaf blight in the ’70s in the United States," he noted, "have shown that if you have one variety, pests will find it and make trouble."

Greater diversity within the crops also allows more genes to select for traits such as tolerance to drought and heat stress, which are expected to increase as the planet warms, Khoury explained.

Another tactic, the paper published Monday noted, is to increase the diversity of crops grown in any given place to provide resilience in the face of climate change. But that tactic is controversial, according to Cassman.

"You could say that it would be great if we had a more diverse diet, but if that included crops that were not as efficient in using land, water, nutrients, it means expanding agriculture to get the same level of production and expanding agriculture means cutting down natural habitat, etc., [which] contributes to climate change," he said. "So, it is not quite that simple."

Shifting diets

Khoury and colleagues said the homogenization trend of global crop production shows no signs of slowing down.

"But does that mean that all of us at some endpoint are really all going to be eating exactly the same thing?" he said. "I doubt it." In fact, in communities around the world there is a trend toward diets that include more cereals and a greater variety of vegetables, he said.

That may reflect growing awareness about the benefit of a healthier diet.

"People seem to be realizing," he said, "that what we eat does affect us a lot."