SAN JOSE, Calif. — Shhh! Our noise is taking the luster off America's natural wonders, and it's affecting the wildlife as well. That's according to researchers at the National Park Service and elsewhere who study natural soundscapes to gauge how they're affected by human activity.

"Both noise and light pollution are growing far faster than the human population of the United States," Kurt Fristrup, senior scientist for the National Park Service's Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, told reporters here at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science on Monday. "They're somewhere between doubling and tripling every 20 to 30 years."

The issue has environmental as well as potentially legal ramifications: A 99-year-old law requires the park service to guard against the impairment of America's national parks — and although Fristrup said noise pollution hasn't yet risen to the level of legal action, it is having an effect on the park experience.

"It has the same effect on your hearing that fog has on your vision," he said.

Bring in the noise?

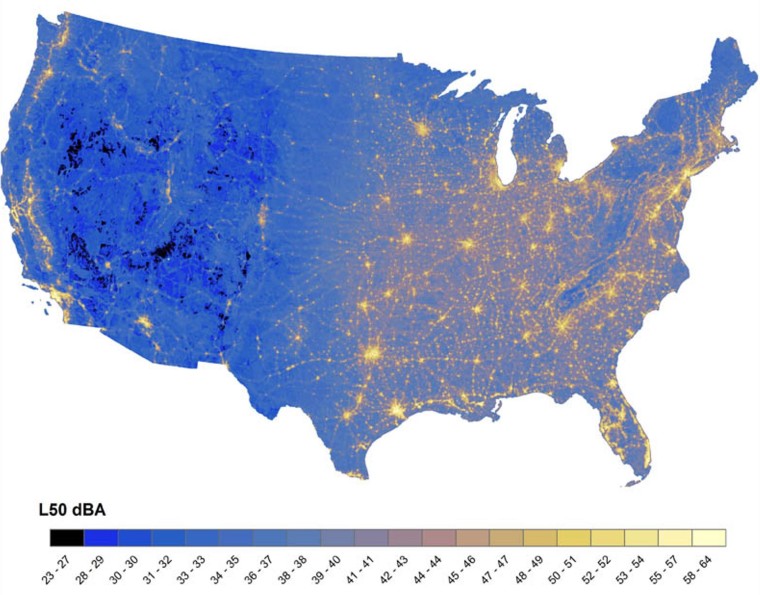

To gauge just how much outside sounds are intruding upon natural soundscapes, Fristrup and his colleagues set up about 600 sound meter gauges in national parks. Then they used computer models to extend those readings to the entire country.

"We find that noise is not confined to the built environment," Fristrup said. Depending on atmospheric conditions, the sound of motorized activity can extend for miles — and it turns out that airplane overflights are a significant contributor to backcountry noise.

He recounted the experience of hiking with friends in Colorado's Rocky Mountain National Park, and asking them later whether they heard any obtrusive noises. "Of course I'm counting them, like 17 jets, three GA [general aviation] aircraft and one helicopter, and most people are astonished when I tell them that," he said.

Fristrup worries that the cacophony of contemporary society could dull the next generation's appreciation of natural soundscapes and lead to "learned deafness."

Studies have shown that the subtle sounds of the great outdoors — such as birdsong, the rustling of wind through the trees, and the trickle of flowing streams — tend to have a soothing effect, while the noise of motorized vehicles is more likely to put people on edge.

"This gift that we're born with — to be able to reach out and hear things that are hundreds of meters away, all these incredibly subtle sounds — it is in danger of being lost to generational amnesia," he said.

Overwhelming wildlife

It's not just humans: Wildlife species are affected by noise as well. A newly published paper reports that anthropogenic noise affects bird species differently, depending on their diet and the pitch of their songs.

Cal Poly biologist Clinton Francis found that noise was more likely to drive out birds that sing in relatively low frequencies, probably because the noise was closer in pitch to the songs. Also, birds of prey were more likely to flee, perhaps because the noise interfered with their ability to listen and hunt.

"These results suggest that anthropogenic noise is a powerful sensory pollutant that can filter avian communities non-randomly by interfering with the birds' abilities to receive, respond to and dispatch acoustic clues and signals," Francis wrote in a study published online Monday by the journal Global Climate Biology.

For some birds, noise is a good thing: Francis said black-chinned hummingbirds are more active in the noisy environment of New Mexico natural-gas wells, perhaps because their predators have been driven away. "Hummingbirds may be benefiting from the absence of key threats during nesting," he told reporters.

However, Francis said noise can have a negative effect on even plant species, by driving away the animals that play a role in dispersing seeds. "It appears as though noise pollution is causing a large-scale decline in pinyon pine seed dispersal," he said.

Keeping things quiet

Is Mother Nature doomed to be drowned out? Not necessarily. "One of the great hopeful things about this particular area is that mitigation can be immediately effective," Fristrup said.

For example, the National Park Service worked out a noise mitigation plan for Yellowstone National Park that rewards tour operators if they find quieter ways to show people the sights. Officials are also working on a plan to address aircraft noise in Grand Canyon National Park, although some environmental groups are dissatisfied with the plan in its current form.

Overflight noise can be a problem for some of America's best-known retreats, such as Denali National Park in Alaska and Yosemite National Park in California. "Yosemite is in the crosshairs of air traffic," going east-west as well as north-south, Fristrup said.

But other national parks are renowned for their noiselessness. If you're really looking for peace and quiet, Fristrup's picks include City of Rocks National Reserve in Idaho, Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve in Colorado and Haleakala National Park in Hawaii.