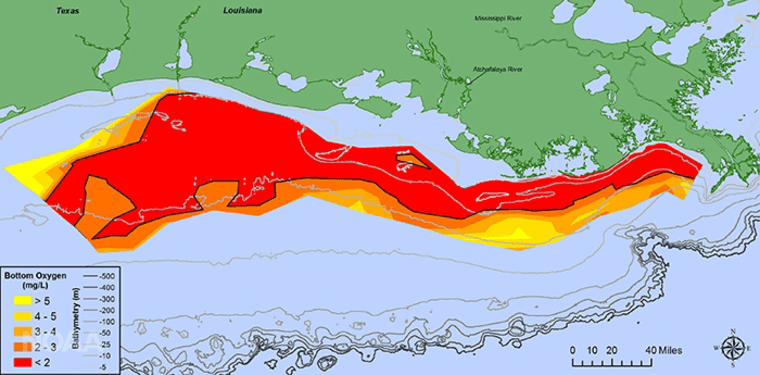

Right now, in the depths of the Gulf of Mexico, lies an area the size of New Jersey that's so oxygen-deprived it's void of almost all marine life.

The so-called "dead zone" isn't a new phenomenon: It appears in the Gulf, and other bodies of water, every summer. But what makes this year's Gulf dead zone unique is its magnitude: At 8,776 square miles, it's the largest ever since tracking began in 1985, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced this week.

Its size is projected to affect local fishing economies and is raising questions over the amount of pollutants that flow into our water — particularly nutrients from excessive use of nitrogen fertilizers.

"It's a symptom of an ecosystem that's not functioning," said Dr. Nancy Rabalais, a professor in oceanography and coastal science at Louisiana State University who has been leading survey missions of dead zones since NOAA started tracking them.

What causes dead zones

The dead zones occur as a result of nitrogen and phosphorus flowing into water from farmers using nutrients on crops as fertilizer, and those nutrients getting washed into streams and rivers by rain.

"It's a symptom of an ecosystem that's not functioning."

Once it gets to the Gulf of Mexico, the nutrients stimulate the growth of algae. The algae then sinks to the bottom of the ocean and bacteria start decomposing the organic matter in the algae. That process uses oxygen, drawing it from the water.

Related: Climate Change Worsens Dead Zones in Seas, Lakes and Rivers: Study

The dead zones grow to their biggest size in the summer because that's when there's more fresh water sitting on top of cold saltwater, blocking oxygen from the atmosphere from mixing with the water underneath. Dead zones then shrivel away as the fall and winter approach.

Man-made versus natural influences

This year's dead zone is particularly large because of unusually heavy rains in the Midwest, which washed more nutrients than usual, primarily from fertilizers, into the Gulf.

"The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico has been growing since the 1950s and 1960s, when much more fertilizer was applied to agricultural land and started going downstream and into the Gulf of Mexico. For the past 20 years, it has been fluctuating up and down. Most of that is due to differences in precipitation and river runoffs," said Robert Magnien, director of the Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research at NOAA.

But the amount of rain is only part of the equation, Magnien said.

"This is not a natural phenomenon, but it is affected by variations in climate or weather patterns."

"We are at a much different place than is natural. This is not a natural phenomenon, but it is affected by variations in climate or weather patterns," he said.

Prior to this year's, the largest Gulf dead zone encompassed 8,497 square miles in 2002. But NOAA said the average size of the dead zone over the past five years was just over 5,800 square miles, and experts can't predict how large next year's will be.

Who's affected

The dead zone has a striking effect on the Gulf: Marine life, such as shrimp, avoid the area, even if their life cycle would normally put them in it.

"They either have to go up over the top of it or around it," said Don Scavia, a University of Michigan professor who was one of the people who discovered the dead zone in the 1980s. "It puts them in different temperature water and a different habitat than they prefer, so that has an impact on their growth."

That's resulted in smaller shrimp, which are worth less to shrimp trawlers.

"Our shrimp fishery depends on small shrimp getting in the nursery areas in the marshes to the actual waters, and that migration is interrupted by this large area of low oxygen," Rabalais, the LSU professor, said. "When the shrimp can get back into the area, the food resources are lower, and they're not growing to a large size that would bring in more money."

Recreational fishing is affected too: Fishermen need to go further offshore to get fresh catch.

What can be done to prevent dead zones?

A spokesperson with the Environmental Protection Agency says a task force has worked for years with the 12 states along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to reduce the size of the dead zones.

"Despite strong efforts, reducing nutrient loads from a vast landscape, where tens of millions of people live and grow the food that feeds the world, is an extraordinarily large task. We can’t declare victory in years when the low oxygen zone in the Gulf of Mexico is much smaller than average, like the drought years of 2000 and 2012. Nor should we declare our efforts in vain when heavy rains and floods make the problem worse," the EPA said in a statement.

Experts suggested greater monitoring of agricultural practices to reduce the amount of nitrogen flowing into the water.

Scavia proposed the Gulf get the same kind of federal protection as the Chesapeake Bay, where a dead zone problem got markedly better after the EPA set limits on nutrient pollution in 2010, despite strong objections from farmers.

"If the states don't meet their load reduction targets, EPA can step in and enforce more reduction," he said. "Imagine doing that with the 25 states that are involved [in the Gulf]. It would be very difficult, but something like that would compel the states and agriculture to do more [than] what they're doing."