By Megan Gannon

Ancient lore has suggested that the Vikings used special crystals to find their way under less-than-sunny skies. Though none of these so-called "sunstones" has ever been found at Viking archaeological sites, a crystal uncovered in a British shipwreck could help prove they did indeed exist.

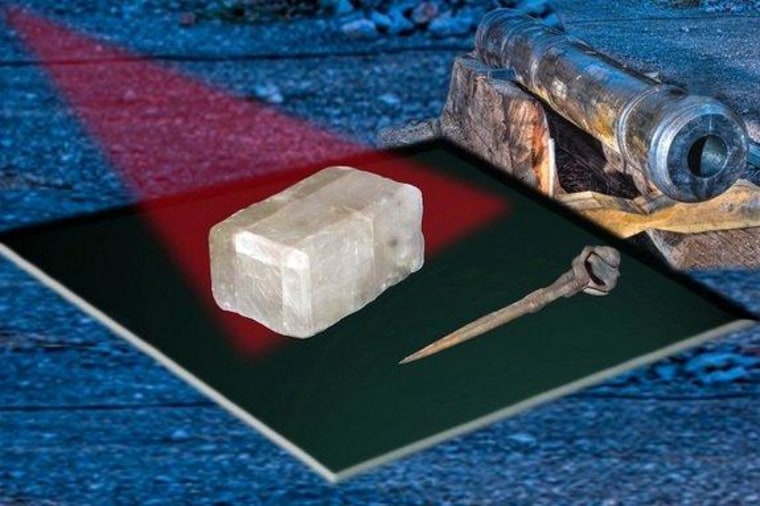

The crystal was found in the wreckage of the Alderney, an Elizabethan warship that sank near the Channel Islands in 1592. The stone was discovered less than 3 feet (1 meter) from a pair of navigation dividers, suggesting it may have been kept with the ship's other navigational tools, according to the research team headed by scientists at the University of Rennes in France.

A chemical analysis confirmed that the stone was Icelandic Spar, or calcite crystal, believed to be the Vikings' mineral of choice for their fabled sunstones, mentioned in the 13th-century Viking saga of Saint Olaf.

Today, the Alderney crystal would be useless for navigation, because it has been abraded by sand and clouded by magnesium salts. But in better days, such a stone would have bent light in a helpful way for seafarers. [Strange & Shining: Gallery of Mysterious Night Lights]

Because of the rhombohedral shape of calcite crystals, "they refract or polarize light in such a way to create a double image," Mike Harrison, coordinator of the Alderney Maritime Trust, told LiveScience. This means that if you were to look at someone's face through a clear chunk of Icelandic spar, you would see two faces. But if the crystal is held in just the right position, the double image becomes a single image and you know the crystal is pointing east-west, Harrison said.

These refractive powers remain even in low light when it's foggy or cloudy or when twilight has come. In a previous study, the researchers proved they could use Icelandic spar to orient themselves within a few degrees of the sun, even after the sun had dipped below the horizon.

European seafarers had not fully figured out magnetic compasses for navigation until the end of 16th century. The researchers say the crystal might have been used on board the Elizabethan ship to help correct for errors with a magnetic compass.

"In particular, at twilight when the sun is no longer observable being below the horizon, and the stars still not observable, this optical device could provide the mariners with an absolute reference in such (a) situation," the researchers wrote online this week in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A.

No such crystals have been found yet at Viking sites. The team notes that archaeologists are unlikely to find complete crystals as part of a group of grave goods, since the Vikings often cremated their dead.

But recent excavations turned up the first calcite fragment at a Viking settlement, "proving some people in the Viking Age were employing Iceland spar crystals," the researchers wrote.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

- 8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

- Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep

- In Photos: 'Alien' Skulls Reveal Odd, Ancient Tradition

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.