Why are the Midwest and the Southeast stuck in a deep freeze, while Alaska is suffering a perilous thaw this winter? The woes associated with this month's unseasonably cold and warm temperatures all go back to the same root cause: a high-pressure ridge that's been locked in for weeks over the American West. And if you think this winter's weather is bad, just wait till this summer's droughts kick in.

"A lot of this is connected," said Brian Fuchs, a climatologist at the National Drought Mitigation Center in Lincoln, Neb. "As we're seeing, the warmth and dryness in the West has implications all the way up to Alaska and also in areas to the east."

The long-lasting ridge causes a kink in the jet stream, sending warm marine air from the Pacific up into Alaska and bringing cold Arctic air down into America's heartland.

The effects are brutal: Midwesterners and Easterners already have suffered through a couple of cold waves, and this week's big chill is disrupting air travel and spreading misery across a region stretching from Texas to Minnesota to the Carolinas. Meanwhile, Alaska's thaw has triggered a mammoth avalanche, cutting off road access to the port of Valdez and stoking fears of flash floods.

Worries in the West

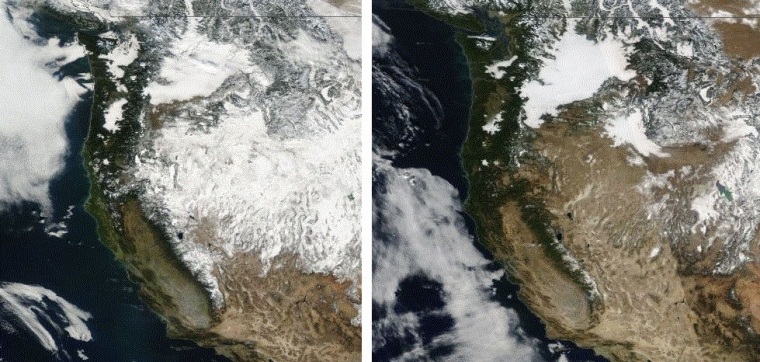

The locked-in ridge is having a more insidious effect on the West. Precipitation has been scarce — so scarce that there's a drought emergency in California and wildfire warnings in Oregon. In January!

Is it possible that this year's drought and fire season will be even worse than last year's? "The current water year, which started in October, is one of the driest on record that we've ever seen," Fuchs told NBC News. "Even if we had near-record moisture from here on out, it would still be tough to make up the deficit."

Last year at this time, drought conditions were in effect for 54 percent of California's land area, Fuchs said. Currently, 94 percent of the state is feeling the drought. "What's happening in the western third of the U.S. is a strong, developing situation," Fuchs said.

This winter is exceptional because the Western ridge has been locked in for so long. "We've seen this happen. Rarely, but it does happen," said Cliff Mass, an atmospheric science professor at the University of Washington who calls the trend "startling and scary" on his blog. "It started in October, and basically it hasn't gone away. There's something causing it, but we don't understand what it is."

The C-word

Whatever it is, don't call it climate change. At least not yet. "It has nothing to do with climate change or global warming," Mass insisted.

James Overland, a weather researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, agreed that it's too early to play the climate card.

"We know there are large changes going on in the Arctic," he told NBC News. "We'll be putting more energy into the Arctic, 20 or 30 years from now. We think the potential for a linkage is there, and some people think they're starting to see some of that now. But most scientists are fairly skeptical that we can prove there's an effect already."

Fuchs said it's hard to attribute any individual weather event to climate change. "Now, is climate change contributing?" he said. "I'm guessing that once we go back and analyze 2013 and 2014, we're going to be able to say, sure, we've seen some longer-term factors that helped intensify or lengthen the change that we've seen."

Relief ... but will it be brief?

So what about the shorter term? Is relief in sight? Yes, for a while, for some parts of the country. "The big blocking ridge finally breaks down over the next few days," Tom Moore, coordinating meteorologist for The Weather Channel, reported in his latest outlook.

Moore said the Plains and the South are in for warmer temperatures, while the cold is expected to continue in the Northeast and the upper Midwest.

It's not clear how much relief is in store. "Looking at a week from now, there's talk about the ridge re-forming again. That would be something like the fourth episode of this very wavy jet stream pattern since the first of the year," Overland said.

"The scientific question is, is there anything in particular that is helping to set up this wavy pattern over and over again?" he said. "That's about as far as we can go."

More about the science of weather:

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ circles. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.