A high-tech team of scientists and filmmakers shared pictures of what appears to have been a centuries-old civilization in Honduras, one year after they used laser-mapping technology to identify traces of structures in the thick jungle.

The square-shaped and rounded structures, seen in computerized elevation maps of a rugged rain forest, may have been the last vestiges of pyramids, palaces and houses in a fabled settlement known as "la Ciudad Blanca," or the White City.

Tales of Ciudad Blanca have circulated since at least 1526, when the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez told King Charles V about a mysterious province called Xucutaco that "must exceed Mexico in riches and equal it in the great size of the towns, the multitude of people and the government thereof." Many explorers have gone in search of the vanished city, driving deep into some of Honduras' roughest and most inaccessible rain forests. Neither riches nor ruins were found.

Nevertheless, the sagas inspired documentary filmmaker Steve Elkins to mount yet another search, this time using an aerial mapping technology known as light detection and ranging, or lidar.

How lidar works

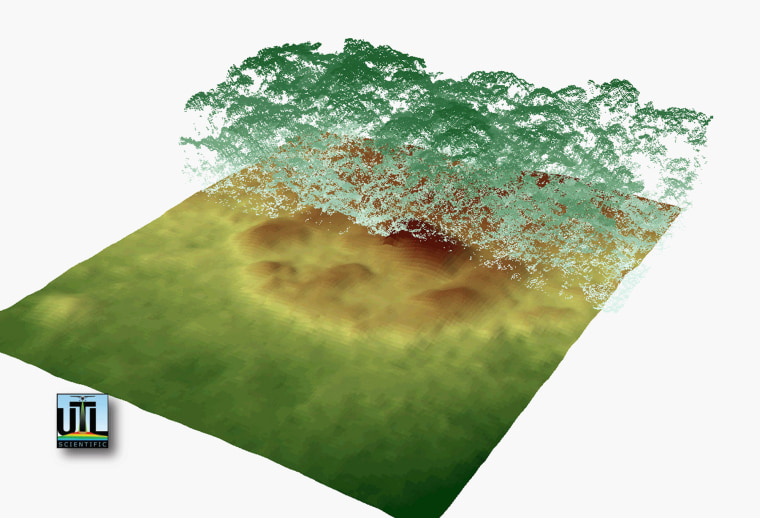

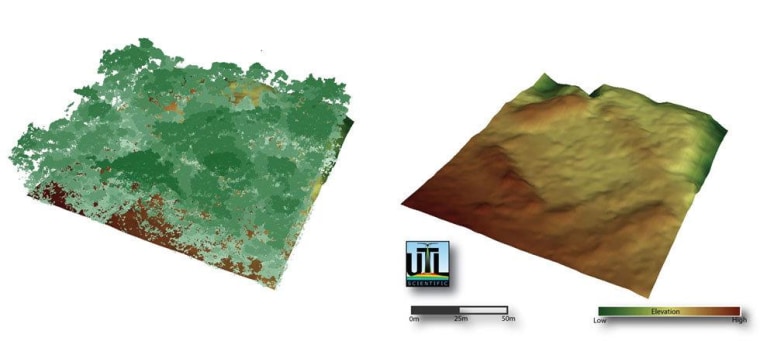

An airplane equipped with the lidar mapping apparatus can bounce laser light off the terrain below, and then gather millions of the reflected readings. Those readings can be interpreted by high-powered software that can produce 3-D maps with an elevation resolution of less than 4 inches (10 centimeters). Such maps can even be "filtered" to peel back the dense vegetation and see the contours of the land below. Using lidar, archaeologists can conduct land surveys that might have required months or years to do on the ground.

"We use lidar to pinpoint where human structures are by looking for linear shapes and rectangles. Nature doesn't work in straight lines," Colorado State University's Stephen Leisz, a member of UTL Scientific's archaeological team, said in a statement from the American Geophysical Union.

Archaeologists once thought the rain forests of Central and South America were too rugged to allow for large, highly organized communities like the one described by Cortez. But over the past decade or so, researchers have found evidence to argue that the forests were once much more highly managed by native populations. The idea that the ancient peoples of the Americas created complex cities and roadways in what are now wild forests no longer seems as radical as it once did. That's what inspired Elkins and his colleagues to go ahead with their search.

An 'easy' discovery

A year ago, the team mapped about 60 square miles (160 square kilometers) of Honduras' Mosquitia rain forest, and sent the data back to University of Houston engineer Bill Carter. Carter, who works with the National Science Foundation's National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping, identified the regular outlines of artificial structures after just a few minutes of analysis.

"It was kind of surprising how easy it was to find them," Carter told The New Yorker.

It took months more to map hundreds of ruins at several sites in the target area. On Wednesday, Elkins and his team shared some their images to fellow researchers during a session at a geophysical science conference in Cancun, Mexico, organized by the AGU. The laser images unveiled this week illustrate how structures could be identified beneath the vegetation, but do not show the settlements in a wider context.

"We can't show the overall place because we'd like to protect the site" from treasure hunters and looters, Elkins explained in the AGU's news release.

He said that the UTL Scientific team plans to explore the structures on the ground later this year. (UTL stands for "Under the Lidar".) Eventually, Elkins and fellow filmmaker Bill Benenson, who is underwriting the expedition, plan to produce a documentary about the latest search for Ciudad Blanca.

More about lost cities:

- How lasers helped spot lost city in Honduras

- Lost city of Atlantis may lie off Spain's coast

- Gallery: Seven tales of cities lost and found

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding the Cosmic Log page to your Google+ presence. To keep up with NBCNews.com's stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.