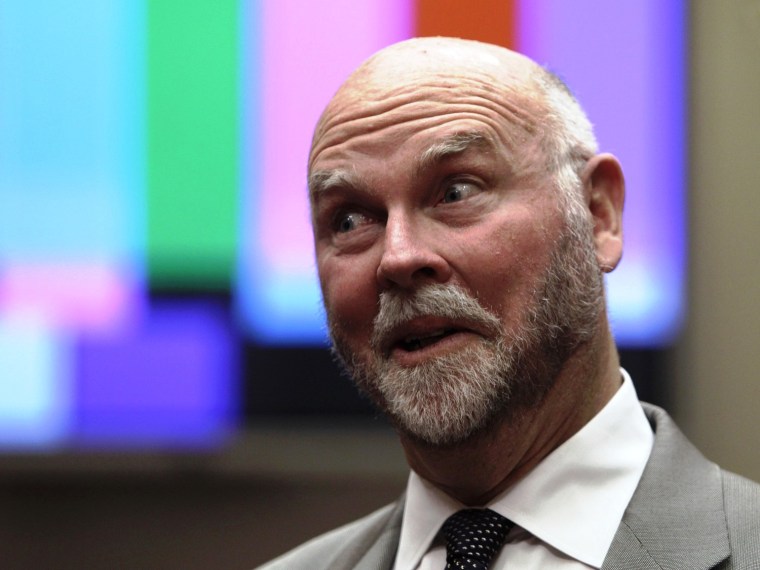

In his latest book, genetic guru J. Craig Venter envisions a brave new world where DNA can be teleported between planets and where custom-made bacteria produce drugs, food and biofuel — but he also worries that do-it-yourself biohackers could spoil that vision.

"One of the concerns that I address in my book is this new emergence of do-it-at-home biology," Venter told NBC News. "One important part of scientific training is that scientists learn the boundaries, the safety issues, how to properly deal with and dispose of chemicals and reagents.

"While it's great at one level that there's excitement and people wanting to do experiments at home, playing with things without the proper knowledge set and the proper training, I think, legitimately raises concerns for an increased chance of unintended consequences," he said.

As Venter points out in his book, "Life at the Speed of Light," he's not the only one worried about biohacker boo-boos. Almost three years ago, a presidential commission on bioethics raised concerns about the risk of "low-probability, high-impact events" such as the creation of a doomsday virus. Bioterror is one aspect of the issue, but Venter says he's also concerned about bio-error — "the fallout that could occur as the result of DNA manipulation by a non-scientifically trained biohacker or 'biopunk.'"

Some have called for more regulation of synthetic biology and home biotech. Venter, however, says overregulation can be as harmful as laxness. It's possible to add built-in safeguards — such as biological kill switches, suicide genes or molecular brakes and seatbelts — to make sure genetically engineered microbes don't escape from the lab. And law-enforcement agencies like the FBI are finding it more advantageous to work with the do-it-yourselfers than to work against them.

The last thing Venter wants to do is kill off the curiosity. "We need to find a way to channel that great level of curiosity into places where people can get proper training, and at the same time exercise their curiosity in a healthy fashion," he told NBC News. "Every university lab and serious research lab has that training. That's where I'd start. I don't think we need a new system for it."

What is life?

In Venter's mind, public ignorance about biotech is a bigger problem than biotech's risks. "It's very hard to have a conversation when over 50 percent of people don't know that tomatoes have DNA in them," he said. "They don't realize that every plant, animal, insect on the planet only exists because it has DNA software. The scaremongers and the worriers, that tells me that we need to greatly improve science education so we can at least start to have an intelligent conversation."

Reading Venter's latest volume provides a good antidote for biotech ignorance: The book was spawned by a talk he gave last year in Dublin, as a follow-up to Nobel-winning physicist Erwin Schrödinger's famous lecture series titled "What Is Life?"

"Life at the Speed of Light" tells the story of biology from the 16th century to the current revolution in genetics, framed as a quest to understand how life is defined.

Venter has had a key role in that quest — as one of the leaders in the race to decode the human genome, as an adventurer seeking to catalog the ocean's microbes, and as the head of a team that created the first synthetic genome in 2010.

Now his main focus is to "rewrite the software" for life, and enlist genetically engineered organisms to manufacture synthetic insulin, vaccines and other kinds of medicines; produce food and fuel for humanity; to clean up toxic waste sites and soak up atmospheric carbon dioxide.

DNA to beam up

One of the tools that Venter and his colleagues are developing for the task is a "biological teleporter," or digital-biological converter. Synthetic Genomics Inc., one of Venter's ventures, has already built a prototype with backing from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. The converter is designed to turn huge strings of digital code into synthetic molecules of DNA.

Future versions of such a device could read the code of an organism robotically at a remote site — say, beneath the surface of Mars — and beam the data back to a lab for reconstruction.

"We can rebuild the Martians in a P4 spacesuit lab — that is, a maximum-containment laboratory — instead of risking them splashing down in the ocean or crash-landing in the Amazon," Venter writes. He suggests that the same technique could be used to reconstruct the life forms of aliens beaming their own information from distant planets. That's assuming, of course, that E.T. is broadcasting the proper code on the proper channel.

And if life's code could be sent at the speed of light from Mars or Gliese 581, couldn't it be sent from Earth to the stars as well?

"In the past decade, since my own genome was sequenced, my software has been broadcast in the form of electromagnetic waves, carrying my genetic information far beyond Earth, as they ripple out into space," Venter says in the book. "Borne upon those waves, my life now moves at the speed of light. Whether there is any life form out there capable of making sense of the instructions in my genome is yet another startling thought that spins out of that little question posed by Schrödinger half a century or more ago."

More about Venter and synthetic biology:

- Venter says 'teleporter' will beam back Martian DNA

- Craig Venter Q&A: Decoding the DNA decoder

- DIY biotech sparks new wonders and worries

- How synthetic biology will change us

- NBC News archive on synthetic biology

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ circles. To keep up with NBCNews.com's stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.