To confirm the theory that humans spread out from Africa tens of thousands of years ago, all you have to do is follow the cold sores. Or, to be more precise, follow the mutation patterns encoded in the genome of the virus that causes those cold sores.

That's what researchers at the University of Wisconsin at Madison did: In the journal PLOS ONE, they describe how they sequenced the genomes of 31 samples of herpes simplex virus type-1 to reconstruct how it hitchhiked on humans as they dispersed around the world.

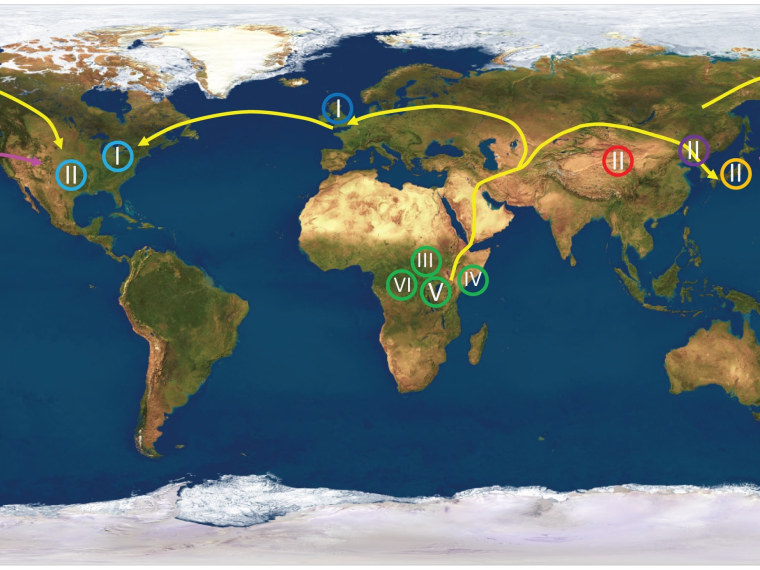

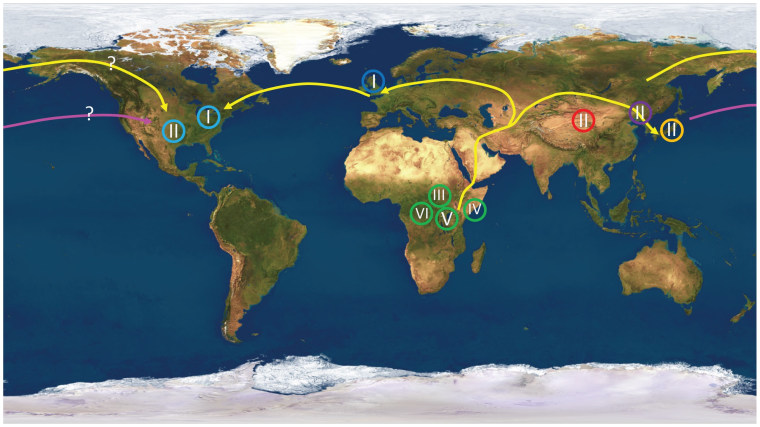

The results match the pattern proposed by the "Out of Africa" theory, which has become the most widely accepted scenario for ancient human migration. The analysis showed that African strains of the virus contained the most genetic diversity — suggesting that they had the oldest roots.

“The viral strains sort exactly as you would predict based on sequencing of human genomes. We found that all of the African isolates cluster together, all the virus from the Far East, Korea, Japan, China clustered together, all the viruses in Europe and America, with one exception, clustered together,” senior author Curtis Brandt, a professor of medical microbiology and opthalmology, said in a UW-Madison news release.

“What we found follows exactly what the anthropologists have told us, and the molecular geneticists who have analyzed the human genome have told us, about where humans originated and how they spread across the planet,” he said.

The findings reflect the view that a small human population passed through a "bottleneck" to get from Africa to the Middle East, then went their separate ways to Europe and Asia, and eventually to the Americas.

Almost all of the samples from the United States were linked to European strains, but one sample from Texas was more closely linked to Asia. Brandt and his colleagues said that particular sample may have come from someone who picked up the virus during a trip to the Far East, or perhaps from someone with Native American heritage whose ancestors passed over a "land bridge" between Asia and North America.

“We found support for the land bridge hypothesis, because the date of divergence from its most recent Asian ancestor was about 15,000 years ago," Brandt said. “The dates match, so we postulate that this was an Amerindian virus.”

The researchers said HSV-1 strains are ideal for tracking long-term migration patterns because they're easy to collect, usually not lethal, and capable of forming lifelong latent infections. Because the virus is spread by close contact, through kissing or exposure to saliva, it tends to run in families. And because the viral genome is so much simpler than the human genome, it's cheaper to sequence.

"While preliminary, our data raise the possibility that HSV-1 sequences could serve as a surrogate marker to analyze human migration and population structures," the researchers say.

More about human migration:

- Lice genes may shed light on human migration

- Rat DNA helps trace migration across Pacific

- Was ancient human migration a two-way street?

In addition to Brandt, the authors of "Using HSV-1 Genome Phylogenetics to Track Past Human Migrations" include Aaron Kolb and Cecile Ane.

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ circles. To keep up with NBCNews.com's stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.