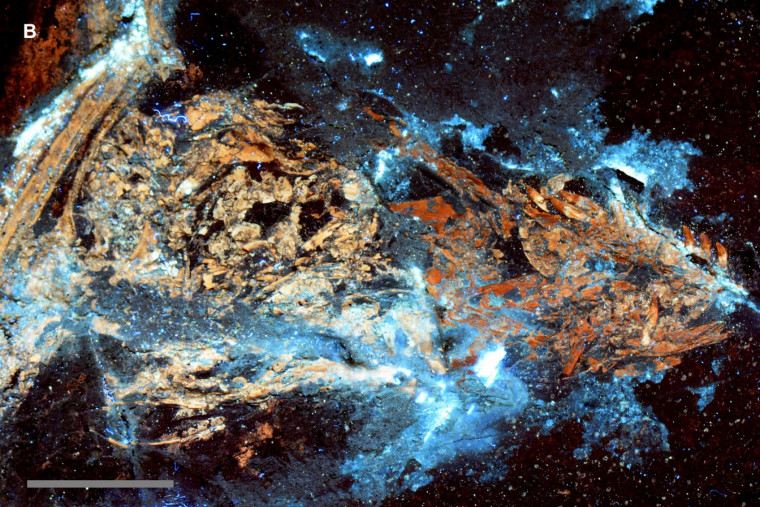

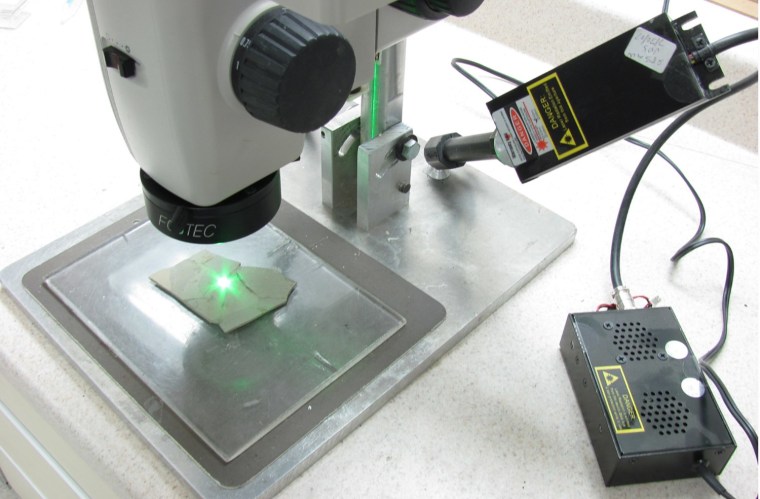

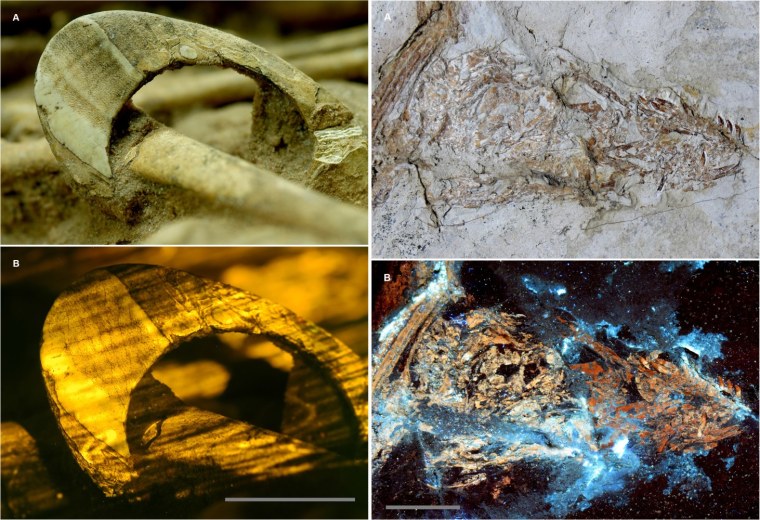

A new technique that uses a laser to illuminate fossils is producing beautiful and fascinating results at the University of Kansas. Shining the laser methodically onto the surface of the fossil or item to be examined causes it to fluoresce, or emit light, depending on what materials it contains. A monochromatic fossil bursts with color when examined this way, since bones, preserved tissues and background rock all fluoresce differently.

University of Kansas paleontologist David Burnham and Thomas Kaye of Seattle's Burke Museum hit upon the technique while trying to identify a fossil that was partly obscured by another fossil in the same specimen. The laser illumination helped separate the two and highlight other hidden materials as well.

"With things like feathers, we can see details really well using lasers," explained Burnham in a news release. "If the fossils themselves won’t fluoresce, the background will. We can see if a primitive feather looks like a modern feather."

The method is also useful for detecting fake fossils that people might try to sell (or have already sold) to museums or universities. Bone shards held together with plaster, for instance, would look very different under the laser light than bones fossilized in their natural state.

And because the technique is non-invasive and fairly easy to perform, it can be used in delicate situations. A bracelet on the arm of a girl buried thousands of years ago was analyzed without having to be removed — researchers found it was made from a hippopotamus tooth.

Researchers detailed the technique in a paper published in the journal PLOS One.