Laser-scanning technology reveals that the Cambodian lost city of Mahendraparvata, dating back to a time before Angkor Wat, was much more extensive than previously thought. The latest word about the high-tech hunt for hidden ruins came over the weekend in an on-the-scene report from Australia's Fairfax Media.

Archaeologists have known about the Hindu-Buddhist-influenced city, situated about 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of the better-known Angkor Wat temple complex, for decades. Some of the ruins rank among the tourist attractions on the holy Khmer mountain known as Phnom Kulen ("Mountain of the Lychees"). However, experts weren't sure how extensive the site was ... until now.

"We're talking about a city that is more than 1,000 years old and is all underground. If you didn't know, you might think it's natural," Stephane De Greefe, the archaeological project's lead cartographer, told Cambodia Daily.

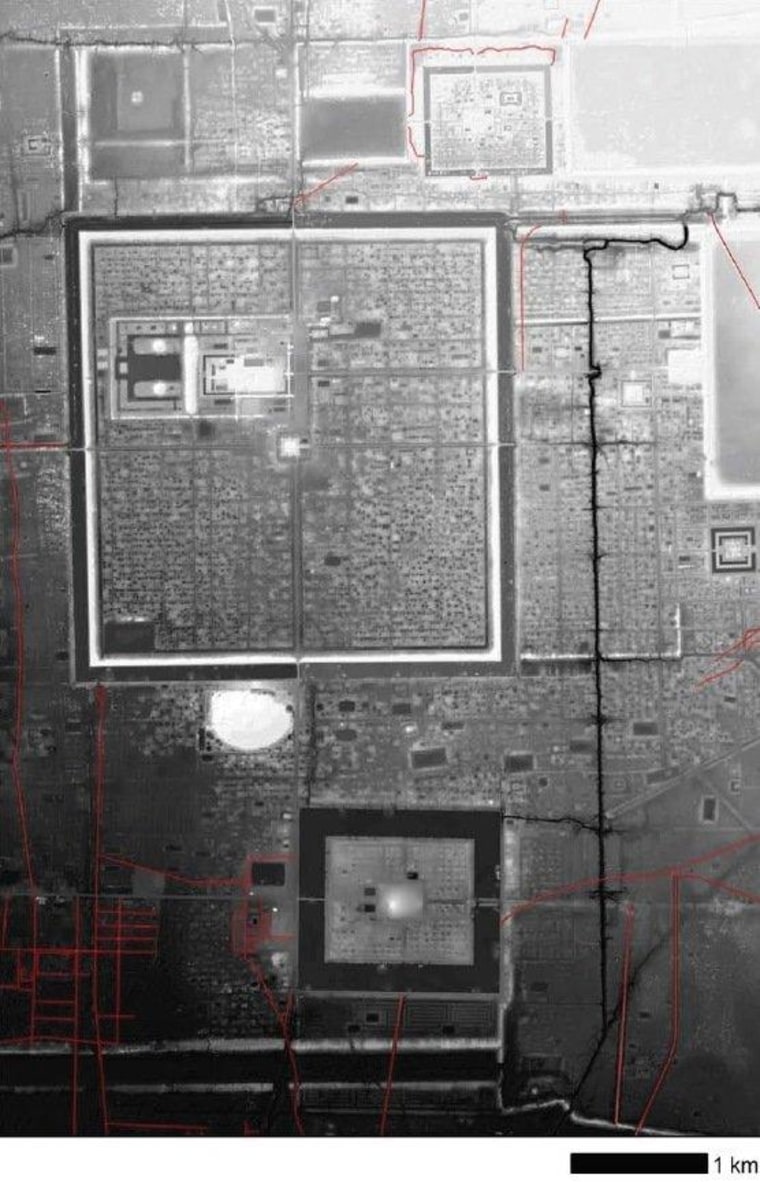

The Khmer Archaeology Lidar Consortium set up an aerial survey of the Mahendraparvata site and its surroundings, using a technique known as lidar (short for "light detection and ranging"). The process involves flying an instrument-equipped helicopter over the area, bouncing pulses of laser light off the ground below, and then analyzing the scattered light readings to produce a 3-D map of the terrain beneath the jungle's vegetation.

Billions of data points and about 5,000 digital photographs were collected during a week's worth of aerial surveys, taking in an area amounting to 143 square miles (370 square kilometers).

'Eureka moment'

University of Sydney archaeologist Damian Evans told Fairfax Media that seeing the map displayed on a computer screen marked the "eureka moment" in a years-long search. The readings revealed dozens of temple sites, hundreds of mysterious mounds that may represent burial sites, and traces of canals and roads criss-crossing the area.

An on-the-ground expedition followed, during which the team came across two temple sites that may still be intact, and a cave with centuries-old carvings that may have been a refuge for hermits during the Angkor period.

Phnom Kulen served as a center of the Angkor civilization between the ninth and the 16th centuries. Tradition has it that Mahendraparvata was where the founder of the Khmer Empire, Jayavarman II, celebrated his people's freedom from Javanese control in the year 802. Angkor Wat was built nearby more than 300 years later.

How a city got lost

Why did Mahendraparvata fade away? "We see from the imagery that the landscape was completely devoid of vegetation" at some point during the site's history, Evans told Fairfax Media's Lindsay Murdoch. "One theory we are looking at is that the severe environmental impact of deforestation and the dependence on water management led to the demise of the civilization. ... Perhaps it became too successful to the point of becoming unmanageable."

Some reports have made it sound as if Mahendraparvata was only now being discovered, but Evans told Cambodia Daily that the real point behind the research has to do with how lidar resolved the debate over the lost city's extent. Lidar surveys are becoming a routine part of "lost city" quests — including the discovery of centuries-old ruins in Honduras that may be linked to the legendary city of Ciudad Blanca, and an extensive survey of Caracol, a Maya center in Belize.

Details about the Cambodian project are to be published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Update for 6:30 p.m. ET June 17: The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences just sent journalists a pre-publication draft of the paper submitted by Evans and his colleagues — suggesting that Mahendraparvata as well as Angkor Wat were part of a vast urban network.

"We identify an entire, previously undocumented, formally planned urban landscape into which the major temples such as Angkor Wat were integrated," the researchers write. "Beyond these newly identified urban landscapes, the lidar data reveal anthropogenic changes to the landscape on a vast scale, and lend further weight to an emerging consensus that infrastructural complexity, unsustainable modes of subsistence and climate variation were crucial factors in the decline of the classical Khmer civilization."

The researchers say their mapping reveals a pattern of regular "city blocks," within which mounds and ponds were built to create temple precincts. Such cityscapes existed in ancient Angkor as well as the Phnom Kulen region and another area farther northeast, known as Koh Ker.

"These 'urban temples' are not isolated; rather, they are nodes in an increasingly concentrated medieval cityscape," they said.

The paper echoes Evans' comments about the potential environmental roots of the Khmer Empire's decline: "The archaeological record shows that episodes of failure were commonplace within the hydraulic infrastructure within the medieval period. ... For several centuries at Angkor, episodic renovation of the water management system offered a series of provisional solutions that were adequate for mitigating the risk of low rainfall on an annual scale. Eventually, however, the civilization was confronted with decadal-scale megadroughts in the 14th and 15th centuries."

The researchers speculate that those megadroughts triggered the doom of Cambodia's megacities. In that, they see a parallel to the classic Maya civilization, which is thought to have gone into decline due to a similar pattern of deforestation and drought. And they include a chilling observation about our own era, attributed to University of Sydney archaeologist Roland Fletcher: "If the infrastructure of low-density cities is inherently liable to be or to become a constraint on the viability of a city’s daily life, then this is an issue of some serious consequence for our engagement with a future of giant, low-density cities."

More about lost cities:

- Scientists share images of Honduran ruins

- Atlantis thought to be found off Spanish coast

- Lost pyramids spotted by space scientists

- Gallery: Seven tales of cities lost and found

The study to be published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences is titled "Uncovering Archaeological Landscapes at Angkor Using Lidar." In addition to Evans, Fletcher and De Greef, the authors include Christophe Pottier, Jean-Baptiste Chevance, Dominique Soutif, Boun Suy Tan, Sokrithy Im, Darith Ea, Tina Tin, Samnang Kim, Christopher Cromarty, Kasper Hanus, Pierre Baty, Robert Kuszinger, Ichita Shimoda and Glenn Boornazian.

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding the Cosmic Log page to your Google+ presence. To keep up with NBCNews.com's stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.