People were hunting and foraging in what is now Florida 14,500 years ago, archaeologists said Friday in a discovery that may settle one debate over when the earliest Americans arrived.

The team used scuba gear to dive into a murky, 20-foot-deep hole in a river to recover the stone tools, mastodon bones and other artifacts that they show people had pushed all the way across the continent thousands of years before conventional wisdom had them even arriving in North America.

“It’s the oldest archaeological site from the American southeast,” anthropologist Michael Waters of Texas A&M University told reports on a telephone briefing. “Clearly humans were exploring and settling the Americas at this time.”

Their research also shows that people lived alongside mastodons for 2,000 years before the elephant-like creatures went extinct about 12,600 years ago. And they found what could be dog bones, although more tests are needed to confirm that.

The findings, published in the journal Science Advances, will have a “long-lasting and profound impact on our understanding of the earliest explorers and pioneers of the Americas,” Waters said.

“It’s the oldest archaeological site from the American southeast."

It also strikes another blow to arguments that the first Americans didn’t arrive until 13,000 years ago in what’s called the Clovis culture, named after a site in New Mexico where distinctive stone tools were found in the 1920s.

The site, called Page-Ladson, had been known for years but the discovery of what appeared to be butchered mastodon tusks and stone tools was largely dismissed by the scientific community. The team, led by Jessi Halligan of Florida State University, went back starting in 2012.

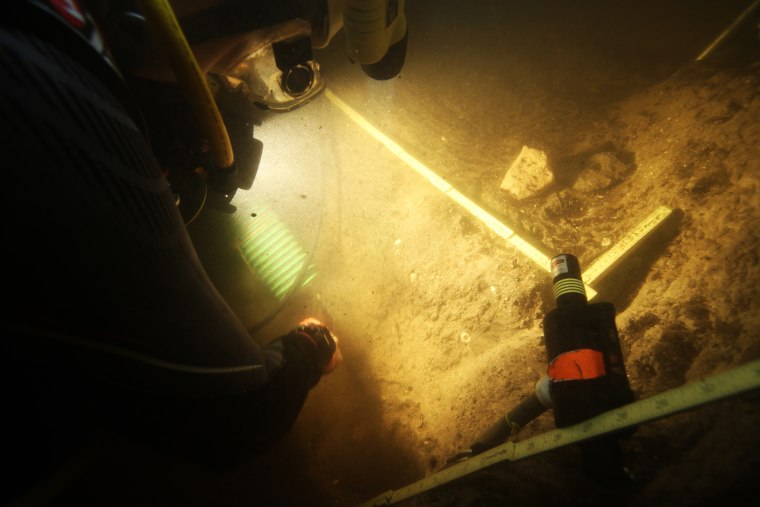

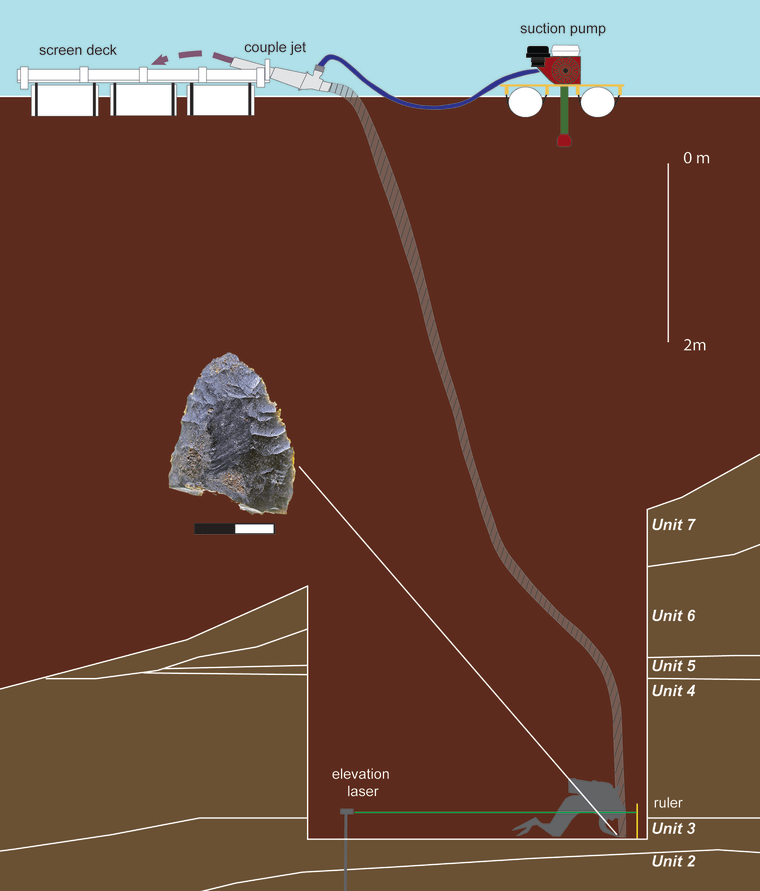

Halligan is a scuba diver and she and Waters assembled a team of experts to do an underwater dig – a technique not often used in the U.S. except to recover shipwrecks. They had to contend with cold water stained black by tree leaves, which meant they could barely see what they were doing.

But they blocked it off just as they would a land site, Halligan said. “We used underwater lasers to control our depth of excavation,” she said. Vacuum tubes gently suctioned away debris before it could cloud what little visibility they had.

They found the rest of the mastodon and more goodies. “These excavations were successful beyond our dreams,” Halligan said.

Carbon dating confirmed that the tools and the bones had been lying under the water for 14,550 years, preserved by the cold, dark conditions under the muck.

There was also plenty of mastodon dung to analyze, and spores found in the dung helped date the site.

The findings paint a picture of people either hunting or scavenging mastodon, traveling over terrain to track their prey. They clearly knew their way around, so they’d been there a while.

“At Page-Ladson hunter-gatherers, possibly accompanied by dogs, butchered or scavenged a mastodon carcass at the sinkhole’s edge next to a small pond at around 14,550(years ago),” the team wrote.

“These people had successfully adapted to their environment; they knew where to find freshwater, game, plants, raw materials for making tools, and other critical resources for survival.”

“These excavations were successful beyond our dreams."

In those days, the oceans were smaller because so much water was still tied up as ice. What was then a sinkhole would have been 120 miles from the coastline of the time. It may have been a water hole used by animals as they moved from place to place -- and by the people who moved with them.

“We have only a handful of things but we pretty sure they were hunters and gatherers. They were fairly mobile on the landscape,” Halligan said.

There are other sites in the continental U.S. that have also been dated to before 13,000 years ago, but only three, and they’re all much further west – in Oregon, Wisconsin and Texas, and there is one site in Chile. DNA evidence suggests that humans were in the Americas long before even 14,550 years ago, but there is no physical evidence to support the idea.

But coastal settlements are almost certainly underwater because of rising sea levels. The earliest Americans migrated from present-day Siberia over a land bridge into Alaska. That’s all underwater now.

“How people made their way to Florida and how long this took we can only speculate,” Waters said.

Now the team's hoping their techniques can be used to find the other sites they are sure lie waiting to be found across the continent.