The 19 firefighters who lost their lives in an Arizona blaze took advantage of the last resort available to them — emergency shelters that look like aluminized sleeping bags — but even those weren't enough to save them.

The shelters are designed to withstand temperatures of 500 degrees Fahrenheit (260 degrees Celsius). That provides a high degree of protection against radiant heat, and shields against intermittent flames. But if the flames come in direct contact with the aluminum covering, the shelter doesn't last long.

For that reason, firefighters are trained to do everything they can to stay out of situations where the shelters have to come into play.

"There's all this training that is just hammered into the firefighters so that you don't get in a situation like this, but if you do, that's the final thing to do," Jennifer Smith, a spokeswoman for the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho, told NBC News.

Standard issue

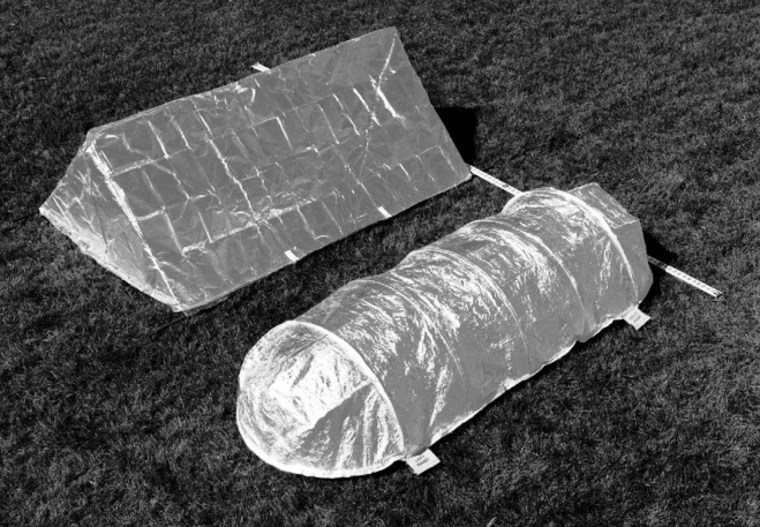

Fire shelters have been standard issue for wildland firefighters since the 1960s, but the classic "pup tent" design was replaced by the current design 10 years ago. Studies show that the new two-ply, sleeping-bag model is significantly better at protecting firefighters from the superheated air and flames that are the killers in a wildfire. The shelter weighs 4.2 pounds (1.9 kilograms), folds up into a pack that's 4.5 inches (11 centimeters) deep, and costs about $250.

Since 2005, 116 of those new-style shelters have been put into use during wildfires, said Tony Petrilli, equipment specialist at the U.S. Forest Service's Missoula Technology and Development Center. They're thought to have saved 21 lives and headed off 90 burn injuries. Petrilli said that, in retrospect, just six of the shelter deployments were not needed. And before Sunday's tragedy, two fatalities were associated with cases in which the shelters were deployed — during the 2008 Panther Fire in California and the 2011 Coal Canyon Fire in South Dakota, Petrilli said.

Safety on the front lines is a balancing act: added weight vs. added protection, aggressively fighting the fire vs. ensuring personal safety, digging in vs. retreating. And just when you think you've covered all the factors, Mother Nature throws you a curve.

The fire that swept through Yarnell, Ariz., over the weekend is still raging, and investigators will be looking into Sunday's 19 deaths for weeks to come. But Wade Ward, a spokesman for the Prescott Fire Department in Arizona, told NBC's TODAY that the elite unit of Granite Mountain Hotshots must have fallen victim to a "perfect storm" of hazards.

"Wind could have been a problem," said Bill Gabbert, a veteran firefighter who is monitoring developments in Arizona's Yarnell fire for his website, Wildfire Today. He told NBC News there were reports that winds in the wildfire zone rapidly shifted 180 degrees on Sunday. "That wind shift might have pushed the fire right up against them," Gabbert said.

Waiting out the fire

In an emergency, firefighters are trained to seek out open spaces and clear away any fuel that might stoke the fire. It takes less than 20 seconds to unfold the shelter. The firefighters climb inside, strap themselves in and lie face-down on the ground, where the air is coolest. If the flames don't come in direct contact, the shelters afford precious minutes of protection. But at 500 degrees F, the aluminum-coated layers start to come apart. And when the temperature reaches 1,200 degrees F (650 degrees C), the aluminum melts. A wildfire's flames average 1,600 degrees F (870 degrees C) and can get much hotter.

The experience of waiting out a fire in the shelter is harrowing: Some veterans have compared it to living through a nuclear blast. "If you hear anything at all, the things you hear you don't want to hear, you wish you'd never heard," one survivor said.

A typical entrapment lasts from 15 to 90 minutes, and the urge to flee can become overwhelming. But that's where the training comes in. "No matter how bad it gets inside, it is much worse outside," the National Wildfire Coordinating Group's fire shelter manual says.

Update for 5:50 p.m. ET July 1: The Forest Service's Petrilli gave journalists additional information about the new-generation fire shelters, including the statistics cited above. He couldn't comment specifically on the Arizona fire, because he still had to head down to the scene for investigation. But he did note that "humans can take up to 300 degrees Fahrenheit for a very short time. Above that, or much longer than a few moments, it will most likely not be survivable."

Petrilli said that fire shelters have undergone only minor design changes in the past decade, but that experts were considering new technologies. "One thing that is being seriously looked at ... is an improvement to the glue that laminates the aluminum foil to the cloth — trying to improve that bond as far as higher temperature."

Over the years, Petrilli has been collecting stories from the survivors who used the shelters, to include in training DVDs. "The No. 1 thing I hear from firefighters is, they can't ever believe they're in that situation and they're doing it," he said. "It's a hard reality to face. ... Being inside the fire shelter, it's quite often difficult for firefighters ... days and weeks and months and years following the incident."

More science of wildfires:

- Blame the beetles? Blame climate change

- Scientists work on wildfire warning system

- Wildfire coverage from NBC News

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following@b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ presence. To keep up with Cosmic Log as well as NBCNews.com's other stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.