I don't advise playing any drinking games on New Year's Eve, but when scientists play with their drinks, the results can make for interesting cocktail-party conversation.

Here's a recap of research relating to the physics and chemistry of liquids in a glass:

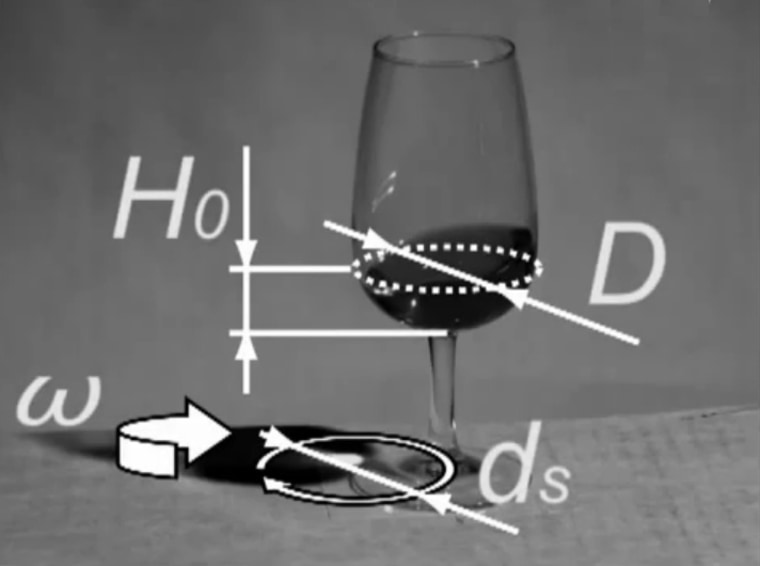

Tweak your twirl: Swirling red wine in the glass aerates the vintage and facilitates the release of all those wonderful aromas that distinguish a Rothschild from rotgut. The ideal is to have one smooth wave breaking around the bowl of the glass, and this year physicists at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland figured out the fluid dynamics of the perfect swirl.

They used glasses of different shapes plus a healthy supply of cheap merlot to study the factors that determined the shape of the wave rolling around the glass. Three factors emerged, as described in this ScienceNOW summary: the ratio of the level of the wine poured in to the diameter of the glass; the ratio of the diameter of the glass to the width of the circular shaking; and the ratio of gravitational force pushing downward to the centrifugal force pushing outward.

A smooth wave can be achieved in glasses of widely varying sizes, as long as the three ratios are preserved. To get a feel for the right level of slosh, study the video below. Be careful not to swirl too vigorously, though: The researchers found that when the merlot was accelerated at 40 percent of the force of gravity, the slosh turned into an unwelcome splash.

Baby your bubbly: French researchers reported last year that the best way to baby that New Year's Eve champagne is to pour it gently down the side of your glass. This is one kind of wine you don't want to slosh: If you do, a lot of the carbonated bubbles are released before you bring the glass to your lips. And it's the bubbles that make champagne so pleasurable. The researchers found that champagne is best served when it's cold (39 degrees Fahrenheit, or 3.8 degrees Celsius). Warmer temperatures cause faster CO2 loss. And besides, who wants to drink warm champagne?

When it comes to serving champagne, narrow-mouthed flutes are currently preferred to wide. saucer-shaped glasses for similar reasons. The greater surface area of the saucer bowl leads to faster CO2 dissipation.

The same research group found that smooth-walled flutes tend to tone down the bubbles in poured champagne, while scratches in the glass promote bubble nucleation. Some glassmakers intentionally put microscratches in the inner surface to create showier special effects. If you want to do something similar, try wiping the inside of the flute with a cloth towel; the tiny fibers that are left behind produce a similar effect on nucleation. This video from the American Chemical Society tells you more about the chemistry of champagne:

Shaken or stirred? Physics and chemistry often determine whether an alcoholic drink takes flight or flops, as Harvard physicists Naveen Sinha and David Weitz explain this month in a report on cocktail physics for PhysicsWorld (free access with registration).

Straight shots of aquavit, vodka or other spirits are best served cold — zero degrees F, or -18 degrees C — because that reduces the burning sensation you get in the throat and chest when you toss the shot down the hatch. But low temperatures also make it harder to savor the taste and aroma of other ingredients, which is why mixed drinks are usually served at higher temperatures.

A nice chill helps balance the taste of a gin martini, though. If it's anywhere close to room temperature, the gin tends to overwhelm the vermouth.

Speaking of martinis, The Straight Dope provides some words of wisdom about the "shaken-vs.-stirred" debate. The way Cecil's pals tell it, a gin martini is best stirred, not shaken — because shaking dissolves more air into the mix, "bruising" the gin and supposedly giving the martini more of a bitter taste.

On the other hand, a vodka martini (which some drinkers refuse to recognize as a martini at all) is best served as cold as possible, and shaking with ice is a more effective way to cool down the drink. Also, shaking breaks down the oils in the vermouth more completely. In case you've forgotten, Agent 007 James Bond preferred his martinis with vodka — and "shaken, not stirred." A decade ago, researchers found that shaking deactivates the hydrogen peroxide in a martini better than stirring does, producing more of an antioxidant effect. They concluded that "007's profound state of health may be due, at least in part, to compliant bartenders."

If you're making a manhattan, don't follow 007's lead. Sinha and Weitz observe that "a manhattan, which contains whisky, vermouth and bitters, can become cloudy when shaken."

"This results from small air bubbles introduced into the beverage while shaking, which are then stabilized by the bitters," they write. "A stirred manhattan, in contrast, is clear, which is why it is typically served stirred, not shaken, unlike James Bond's martinis."

For more about the physics of mixology, including a high-tech recipe for a hot and cold gin fizz, check out the full report from Physics World. Whatever you do, drink responsibly ... and have a happy and safe New Year's Eve.

More about the science of alcoholic drinks:

- The high-tech cocktail: Future happy hour is now!

- Eight ancient drinks uncorked by science

- How to pour that drink, scientifically

- The why behind a wine's bouquet

Alan Boyle is msnbc.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the log's Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding the Cosmic Log page to your Google+ presence. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.