SEATTLE — Hurtling space rocks like the one that traced a blazing streak across the Russian sky last year slam through Earth's atmosphere on a regular basis, according to data from a system used to detect nuclear weapons explosions. And there’s no way to tell when the next one is coming.

The bright flare of the Russian meteor was hard to miss, and left 1,200 people injured in February 2013. What the human eye missed was two separate high-altitude explosions that occurred over Argentina and the North Atlantic Ocean just months later. That’s according to data from an infrasound network used to track nuke tests, released Tuesday by the B612 Foundation.

Right now, we can only know about these incoming asteroids after the fact, the foundation said.

“Because we don’t know where or when the next major impact will occur, the only thing preventing a catastrophe from a ‘city-killer’-sized asteroid has been blind luck,” said B612 co-founder and CEO Ed Lu, a former NASA astronaut.

The two blasts are among 26 explosions attributed to incoming asteroids since 2000, based on an analysis of data from the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization's sensor network.

None of the asteroids was detected in advance, and in most cases the explosions occurred too high up to have any impact on Earth. Nevertheless, their characteristic signals were registered by the CTBTO's network and analyzed by Peter Brown, a meteor researcher at Western University of Ontario.

Lu said that the statistical analysis was the subject of a paper published in the journal Nature last November, but that the specifics for asteroid impacts between 2000 and 2013 were laid out for the first time in a video visualization released Tuesday. Brown is continuing to analyze the impact data for a forthcoming scientific paper, Lu said.

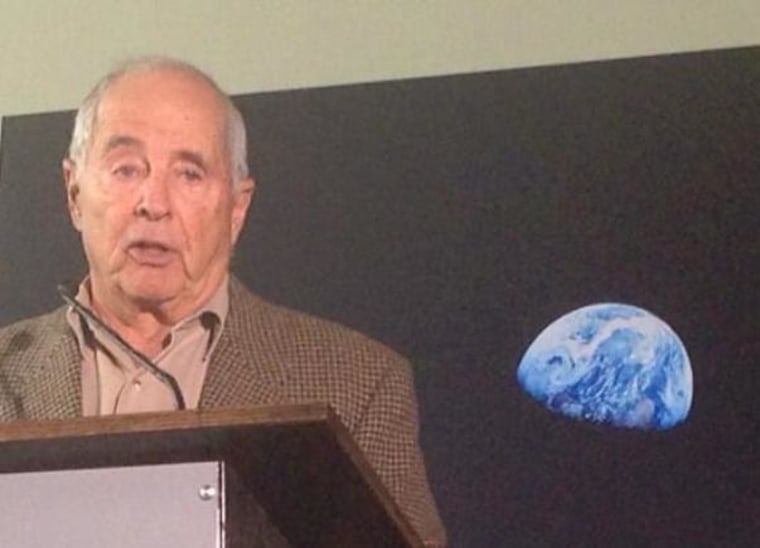

The B612 Foundation released Brown's list to support its campaign to build and launch an asteroid-hunting Sentinel Space Telescope. Lu joined to join Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders and former shuttle astronaut Tom Jones to discuss the project Tuesday at Seattle's Museum of Flight.

Anders said the Sentinel project "sounds like something that we as humanity ought to be doing."

"This is what I think Earth Day is all about," Anders said as he stood in front of the "Earthrise" photo of our planet as seen from the moon — the photo he took during his round-the-moon mission in 1968.

Blasts attracted attention

Each of the 26 explosions listed Tuesday gave off enough energy to equal the detonation of 1 kiloton or more of TNT. The Chelyabinsk blast was the biggest, at roughly 600 kilotons. In comparison, the nuclear blast that devastated Hiroshima in 1945 was 12 kilotons.

Three other explosions were recorded with an estimated energy release greater than 20 kilotons: over the Mediterranean Sea in 2002, the Southern Ocean in 2004, and Indonesia in 2009. Witnesses marveled at the 50-kiloton Indonesian meteor blast, and at the time, some experts said it was the biggest object to hit Earth in more than a decade.

The 2002 Mediterranean blast occurred during a face-off between India and Pakistan over the disputed Kashmir region. U.S. military officials said that if the asteroid had entered Earth's atmosphere a few hours earlier, it might have touched off a nuclear war.

Yet another explosion on the B612 list attracted attention in 2012, when a meteor streaked through the skies over Nevada and California. That asteroid breakup released 5 kilotons of energy, experts said.

Although the Chelyabinsk meteor was the only one on the list to cause damage, Lu said the infrasound data suggested that asteroid impacts were at least three times more common than previously thought. Asteroids capable of wiping out a city, in the range of 130 feet (40 meters) in diameter, might blast Earth every century rather than every few hundred years, he said.

How big is the problem?

The most recent example of an asteroid impact capable of wiping out a city is the Tunguska blast of 1908, which released on the order of 5,000 to 20,000 kilotons of energy (5 to 20 megatons). Fortunately, that asteroid blew up over Siberian forest land instead of a populated area, flattening 500,000 acres of trees but causing no known injuries.

Lu acknowledged that not every "city-killer" will kill a city. "The question is, really, what are we going to do about it?" he told NBC News. "Is this something where we want to sit here and just go, 'Well, we hope we're going to continue to get lucky'? ... One of the things we should be spending our effort on is protecting our own planet."

Experts say nearly all of the near-Earth asteroids big enough to wipe out civilization have been detected and are being tracked — but they add that they've spotted only a small percentage of an estimated million smaller asteroids that are nevertheless capable of causing damage. Lu said B612 is seeking to raise about $250 million dollars to put the Sentinel Space Telescope into an orbit that would detect far more such asteroids. Launch is currently planned for 2018.

NASA budgets about $40 million annually for asteroid detection, and in advance of Tuesday's news briefing, some scientists debated how much more money needs to be spent.

"We are doing plenty, spending more money to do more is silly, and usually justified by fear mongering. ... Once-a-century events with no more consequence than the worst hurricane each year seem unworthy of our worry or investment," Caltech astronomer Michael Brown said Monday in a series of Twitter updates.