Skywatchers could be treated to a Memorial Day weekend meteor shower tonight – but scientists can’t quite be sure.

When Earth passes through the trail of Comet 209P/LINEAR, the mystery meteor shower could produce hundreds of shooting stars in the course of an hour. Or it could be a total no-show. It all depends on how much space debris the comet has left behind over the course of centuries.

Not even SETI Institute meteor astronomer Peter Jenniskens, who was among of the first to sound the alert about the potential for a new meteor shower, knows how the show on Friday night (and early Saturday morning) will turn out. "The situation with the meteor shower itself is the same as it was 10 years ago when we first noticed this opportunity," he told NBC News.

Jenniskens and a colleague, Finnish mathematician Esko Lyytinen, figured out that Earth would pass right through a sweet spot in Comet 209P/LINEAR's orbit on the night of May 23-24, 2014. The comet, which was discovered in 2004 by the LINEAR sky survey, has been swinging between the orbits of Earth and Jupiter for centuries — and leaving behind trails of cosmic dust every time it passed through.

Meteor showers occur when Earth passes through a substantial trail of cometary debris. Those bits of grit zip through the upper atmosphere and spark bright trails of light. Comet 209P/LINEAR's trails haven't matched up with Earth's orbit in the past, but this year, the alignment should be ideal.

"We found that a lot of these trails from the past are actually in Earth's path," Jenniskens said. "They're all sort of piled up on top of each other."

How much debris is in those trails? "The big mystery, and nobody knows, is whether the comet was shedding dust in the 18th, 19th and early 20th century," Jenniskens said. "If it was dormant, we may not see anything at all."

But if the comet was active back then, skywatchers could see 100 to 400 meteors per hour under peak conditions, maybe even more. That could put it in the same league as the Leonid meteor storm of 1999. What's more, the timing is ideal for North American observers.

"If there's going to be a meteor shower, it should show up this year," Jenniskens said. "Keep your expectations low, but make sure not to miss it, because this event has potential."

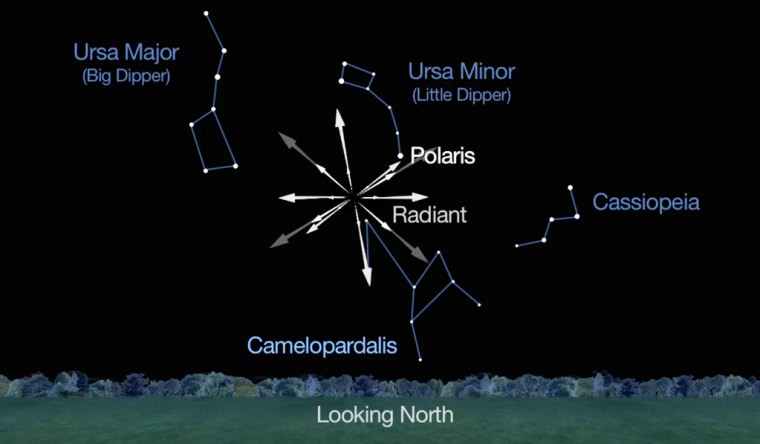

The shooting stars would appear to emanate from a point near the North Star, in the dim constellation Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). That's why the meteor shower has a name that's a real mouthful: the Camelopardalids.

Some meteor showers are known for their fast streakers, but the debris from Comet 209P/LINEAR is expected to plow through the atmosphere at a mere 43,400 mph (19.4 km/sec), Jenniskens said. "Instead of seeing these swift streaks in the sky, what you'll see is meteors that glide through the air, in stately motion," he said.

The timing is critical: If there is a meteor storm, it's not expected to last more than an hour or two. Jenniskens is targeting 3:18 a.m. ET Saturday for the peak, but other astronomers have come up with different predictions, ranging between 2 and 4 a.m. ET.

It's a good idea to check with the SETI Institute's Java-based Fluxtimator app, which offers three prediction models and is accessible via http://meteor.seti.org. (Word to the wise: You may have to fiddle with your computer's Java security settings to make it work.)

How to see it in person or online

Plan to get to your viewing spot before the predicted peak. The best spots are far away from the glare of city lights, with an unobstructed, clear view of the sky. Bring a comfy lounge chair or blanket to lie on, and give your eyes plenty of time to adjust. (Check out these tips from last year's Leonids for more advice.)

To keep track of the meteor buzz via social media, check in with the Camelopardalids Facebook page, which is hosted by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, or watch for Twitter updates with the hashtags #meteor and #camelopardalids.

Seeing meteors flash outdoors is obviously dependent on the weather. But if you're clouded out, you can still get in on the action online:

- The Slooh virtual observatory is planning a marathon webcast starting at 6 p.m. ET Friday. Views of Comet 209P/LINEAR, which just happens to be passing through our celestial neighborhood, will be streamed from telescopes on the Canary Islands. Live coverage of the meteor shower begins at 11 p.m. ET, with commentary from Slooh's Geoff Fox and Paul Cox. Jenniskens is due to be one of the guests on the show. You can tune in via Slooh.com, YouTube or Slooh's iPad app.

- NASA is offering a live video view of the skies over Huntsville, Alabama, starting during the run-up to the meteor shower. Bill Cooke, an expert on meteors at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, will participate in a Web chat from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. ET. You should be able to access the chat as well as the Ustream video via this Web page. While you're waiting for the show to begin, take a look at NASA's six-page guide to the Camelopardalids.

- The Virtual Telescope Project 2.0 has partnered with astrophotographers in the United States and Canada to stream sky imagery starting at 1:30 a.m. ET (0530 GMT). Italian astrophysicist Gianluca Masi is in charge of the event and will provide commentary.

- Even if you can't see the meteors, you can still hear them — thanks to SpaceWeather Radio. When meteors pass over a specially configured radio antenna in New Mexico, the 54 MHz TV signals reflected by the meteor trails are registered and translated into weird-sounding audible whistles. This audio file demonstrates how they sound.

Jenniskens has arranged to look for the Camelopardalids from an instrument-equipped airplane flying out of California. "We will be going into the skies just to have a good, clear view of this," he said. "We're bringing night-vision cameras to measure precisely how the dust is distributed."

From his vantage point, Jenniskens will be able to determine definitively whether the Camelopardalids are a hit or a flop.

"If there are no meteors, I'll be disappointed," he said. "But as a scientist, I will have learned something. We'll know that the comet was dormant long before it was discovered. It's cool to be able to look into the past that way."

Got pictures to share? Alert us to them by using the hashtag #NBCMeteor on Twitter or Instagram, submitting your favorites via our FirstPerson photo-upload page, or sharing them on the NBC News Science Facebook page.