Some people may be disappointed that NASA's next Mars rover won't conduct a life-detection experiment, but hunting for currently existing Red Planet microbes is decidedly premature at this point, mission planners say.

NASA officials announced Tuesday that the agency's new Mars rover, which is slated to launch in 2020, will hunt for evidence of past life and collect samples for eventual return to Earth. The scientists who drew up goals for the mission considered recommending life-detection gear, which NASA's twin Viking landers carried in the 1970s, but the planners ultimately decided against it.

"To date, the evidence that we have from observations of Mars and Martian samples is that we don't have the clear indication that life is at such an abundance on the planet that we could go there with a simple experiment like Viking (had) and detect that (life) there," Brown University professor Jack Mustard, chairman of the 2020 rover mission's Science Definition Team (SDT), told reporters Tuesday. [NASA's 2020 Mars Rover (Images)]

"To go and look for simple organisms, or not-so-simple organisms, that are living within that toxic, harsh environment we just think is a foolish investment of the technology at this time," Mustard added.

It makes more sense right now to look for signs of past life, scientists said, for Mars was much warmer and wetter in the ancient past than it is today. Indeed, observations by NASA's Curiosity rover led scientists to announce this past March that the Red Planet could have supported microbial life billions of years ago.

"It's not just the instrumentation and the basis of the science, but it's also a matter of maximizing potential return," said SDT member Lindy Elkins-Tanton, director of the Carnegie Institution for Science's Department of Terrestrial Magnetism.

"If we were only looking for what microbes could be found on the surface in this place right now, that's like a tiny snapshot of the history of Mars and the possibility of life," Elkins-Tanton added. "But if we look back through the rock record, we're basically integrating over time and maximizing our chances of finding results."

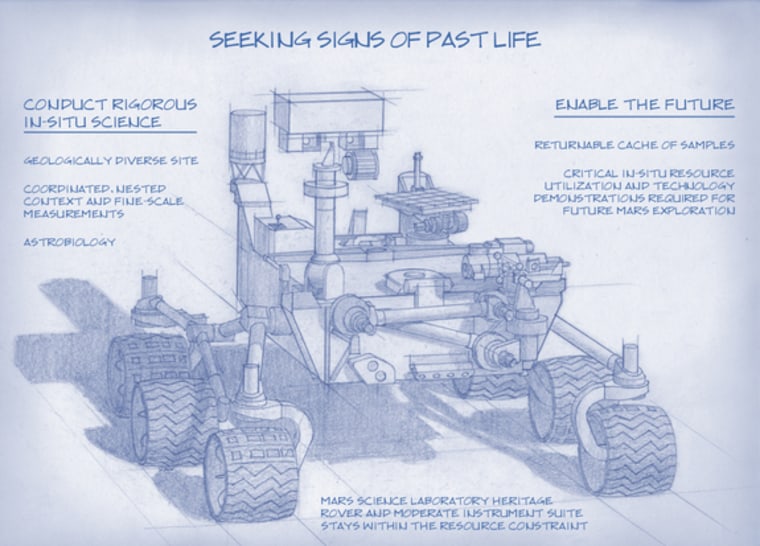

NASA announced the 2020 Mars rover mission this past December, and the agency formed the SDT a month later. The rover will bear a strong resemblance to the car-sized, six-wheeled Curiosity, featuring the same chassis and employing the same "sky crane" landing system that delivered Curiosity to the Martian surface last August.

Curiosity is powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), which converts the heat produced by the radioactive decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. The 2020 rover may utilize the same power system, but it may also rely on solar panels, NASA officials said.

It's also unclear where the 2020 rover will land and what instruments it will carry. NASA plans to put out a call for instrument proposals a few months from now, officials said, and the agency will select a landing site much further down the road, after extensive input from the scientific community.

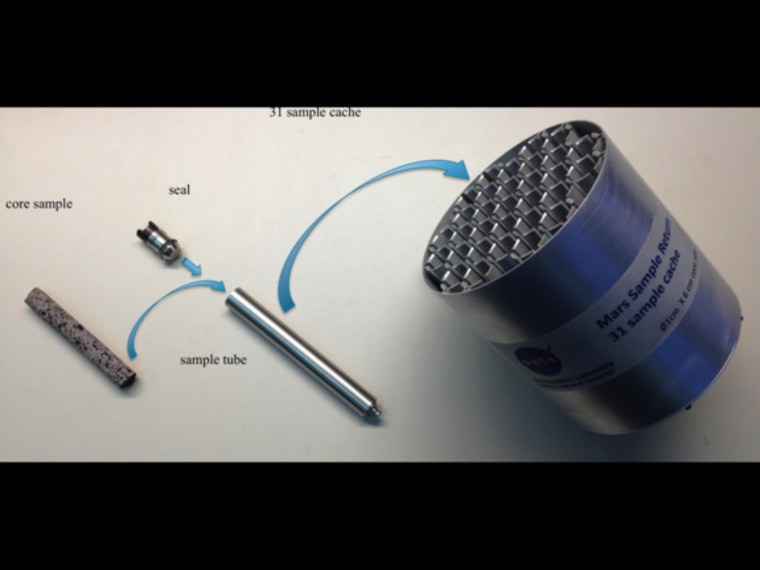

Most scientists regard Mars sample return as the best way to search for signs of Martian life, so the SDT recommended that the 2020 Mars rover collect and cache particularly promising material. But there is no timeline at the moment for bringing these samples to Earth for study.

"At this point, we haven't gone in the forward planning — the next 10, 20 years or so — to show how we would then acquire that cache and return it to Earth, although we've done a number of studies in that direction," said NASA science chief John Grunsfeld. "That's all forward work."

No surface mission has undertaken a dedicated Mars life hunt since the twin Viking landers ceased operations more than 30 years ago. Viking's biological experiments returned intriguing but ambiguous results that scientists are still interpreting and debating today.

Visit here to see the entire 160-page Mars Rover 2020 Science Definition Team report.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

- The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)

- Mars Could Have Supported Life, NASA Finds | Video

- Mars Explored: Landers and Rovers Since 1971 (Infographic)