Warming oceans are pushing fish toward the poles in search of cooler waters, according to a study that raises new concerns that climate change is robbing the tropics of a primary source of income and nutrition.

Meanwhile, in higher latitudes, data show that trawlers are hauling more warm-water fish out of the ocean – a phenomenon that will change what shows up on menus at locavore restaurants from Cape Town to Tokyo.

"There'll be changes in the kinds of fish that are available to people who would like to follow that kind of (eating local) strategy," Michael Fogarty, a fisheries biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Northeast Fisheries Science Center, told NBC News.

Fogarty was not involved with the new research, which he said confirms "what people have seen in different ways but usually on a more localized level." The global perspective published today in Nature, he added, put the fishing industry and consumers on alert that they'll need to adapt to climate change.

Fish as thermometers

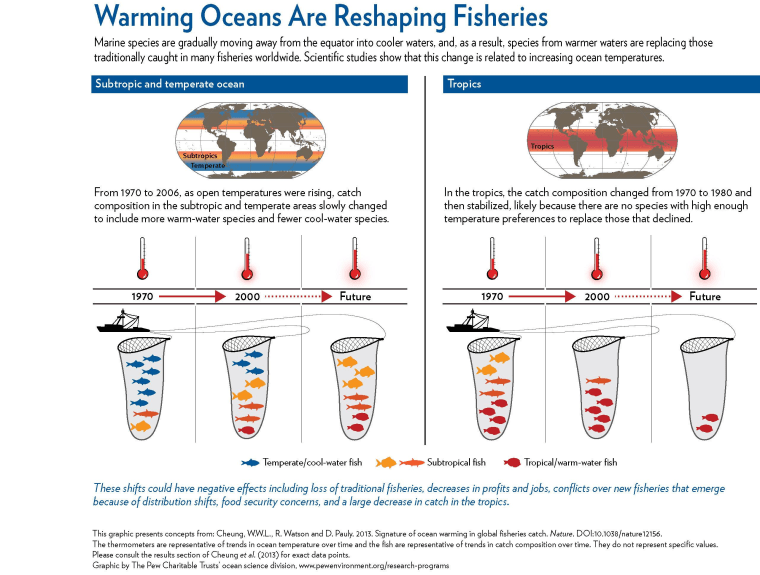

The research used the temperature preference of fish and other marine species as a thermometer to assess the impact of climate change on the world's oceans between 1970 and 2006. Atlantic cod, for example, have a colder preferred temperature than tropical grouper.

The preferred temperature of all the species caught in a particular region, in turn, provides a snapshot of a fishery in space and time that can be tracked to see the impact of warming oceans.

"If the catch composition is having more and more warm-water species present in it, then the mean temperature of the catch will also increase," William Cheung, a fisheries biologist at the University of British Columbia, explained to NBC News.

He and his colleagues found that global fishery catches are increasingly dominated by warm-water species as a result of fish migrating out of the tropics toward the poles. For example, in British Columbia, Canada, tuna and mackerel are more abundant while sockeye salmon are declining.

Meanwhile, the tropics are losing fish. Those that remain are adapted to the warmest waters.

"If the temperatures continue to warm in the tropics, then even these hot-water adapted species will find it difficult to live in the tropics, so we would expect as a result that the fishery production potential in the tropics will decline," Cheung said.

Given that many communities in the tropics rely on fishing for income and food, this trend highlights their particular vulnerability to climate change, he added.

What to do?

"Climate change has made it to the fishmonger and onto our dining tables," Mark Payne, a marine scientist at the National Institute for Aquatic Resources in Denmark, writes in a Nature perspective article about the new study. "The question now is, how should we respond?"

According to Cheung, policymakers and fisheries managers ought to reduce existing stresses on marine ecosystems such as overfishing, habitat destruction and pollution in order to increase their resilience to climate change.

In addition, the world's fishing industry should prepare for the expected changes in species composition.

"Ultimately, it is important to reduce greenhouse gas emissions," he said. "Because if we reduce that, then we know that the rate of change in sea surface temperature will be reduced and this would actually reduce the level of response in terms of fish stocks to climate change."

John Roach is a contributing writer for NBC News. To learn more about him, visit his website.