Yosemite National Park's Rim Fire dashed the plans of many campers over Labor Day weekend. The iconic views of Half Dome and Yosemite Valley's sheer granite walls disappeared behind a sudden influx of thick smoke the night of Aug. 30, just before most visitors arrived for the holiday. The air quality was deemed to be unhealthy for outdoor activities, according to California air quality officials. Smoke from the still-burning fire continues to cause unhealthy air quality levels for sensitive people in nearby cities, such as Fresno, Calif.

The Rim Fire is an omen for the West, according to a new study of future wildfire activity and smoke pollution. The researchers behind that study are predicting more smoke pollution — even in communities far from the forest's edge — as more fires burn because of rising temperatures.

The guilty party behind the new forest fire patterns is climate change, the researchers said. Higher average temperatures will result in more wildfires by 2050, especially in August, they found.

"Fires are started by human activity or lightning, but it's weather that determines the spread of fires," said Loretta Mickley, a study co-author and atmospheric chemist at Harvard University.

Relative humidity and precipitation are also key players in wildfires, but the study found temperature was the primary driver for future wildfires, at least in the West's near future. From the Great Plains to California, the predicted temperature increase is between 4 and 5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.2 and 2.8 degrees Celsius) between now and 2050.

Overall, the typical four-month fire season will gain three weeks by 2050, the researchers report. And the probability of large fires could double or even triple. The findings were published in the October issue of the journal Atmospheric Environment.

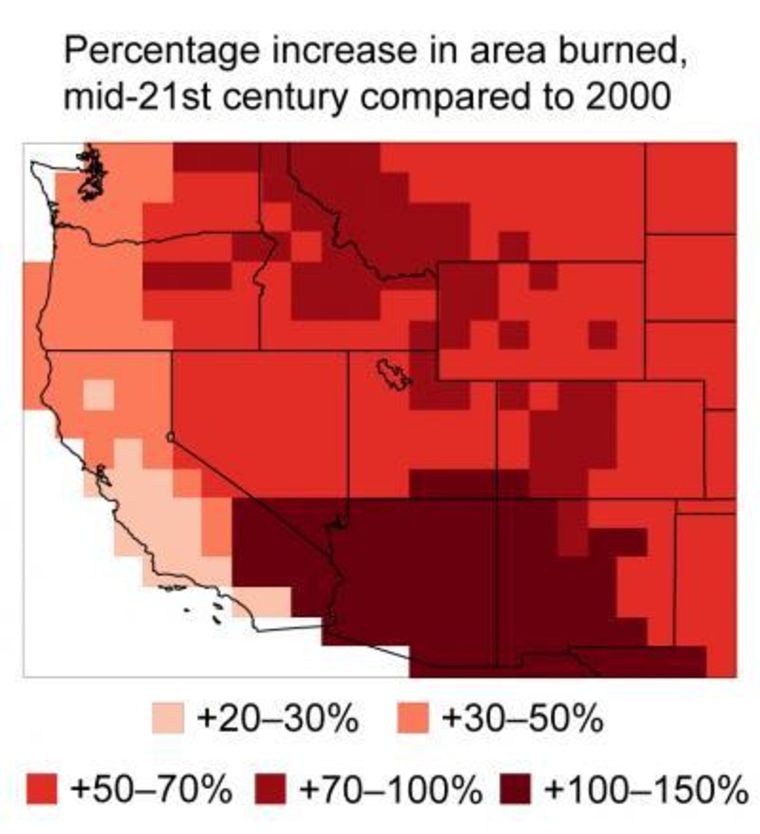

Mickley noted that some Western regions will respond much more strongly to the predicted climate change.

The Eastern Rocky Mountains and Great Plains regions will see their area burned during August nearly double. Also in August, the Rocky Mountain forest acreage torched by fire will quadruple, and the Pacific Northwest will increase by 65 percent, the study suggests. [World Set a Flame: 2002 - 2011 Visualized]

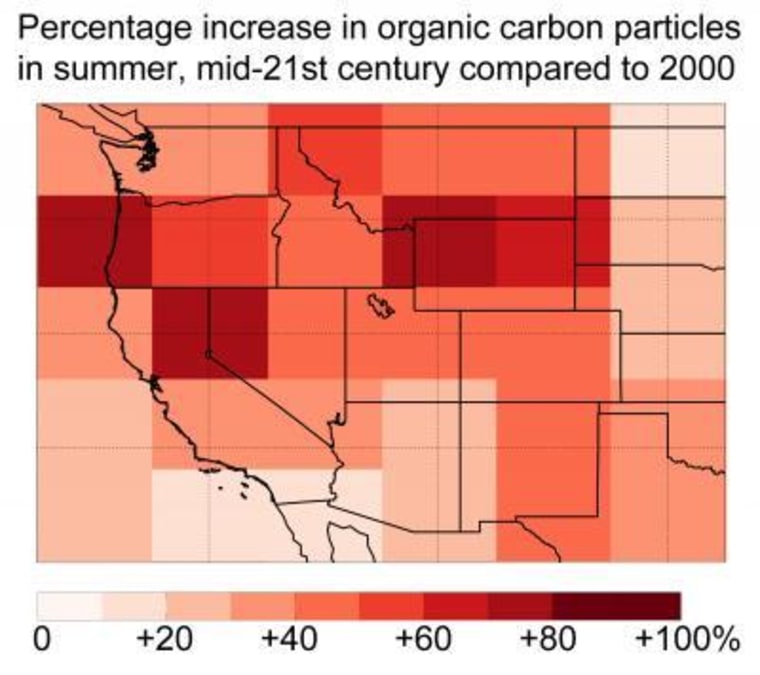

And even distant communities outside the fire zones will feel the impact, from soot and aerosols wafted on winds. The rise in pollution will vary by region, but could jump up to 70 percent in some areas for PM2.5, a measure of fine particles in the air, said Xu Yue, lead study author and a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University. For example, a fire in California's mountain forests produces more smoke than a desert fire because it burns more fuel — in the form of trees, underbrush and littered debris — than a fire in the sparse desert. The Rocky Mountains, the Pacific Northwest and Northern California will be hardest-hit areas, the study predicted.

"We are now working to determine how this increase in wildfires will affect the health of people in the western U.S.," Yue told LiveScience.

To make their predictions, the researchers first created fire prediction models that were tested against real-world data from 1980 to 2004. These fire models were pushed into the future with the 15 climate models from CMIP3, the internationally produced global climate models. The future fire predictions varied wildly, from extreme fire scenarios to a decrease in wildfires. The study offers the median of all the climate model predictions, Yue said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

- Yosemite Aflame: Rim Fire in Photos

- 8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World

- Amazing Video: The Speed Of Wildfire